Opinion, Philippine Daily Inquirer / June 12, 2021

A secret society plotting to mount a revolution against the Spanish colonizers, the Katipunan was discovered by Spanish authorities when in 1896 the sister of Teodoro Patiño, a member of the KKK, found out about the plot and told the Mother Superior of the orphanage where she lived. The nun in turn informed the parish priest of Tondo about the organization, prompting him to rush to the colonial authorities, thus setting off a manhunt for those involved in the plot or even just suspected of supporting the Katipunan. With their backs against the wall, Katipunan leaders, led by Andres Bonifacio, Teodoro Plata, Ladislao Diwa, and others, declared the onset of the Philippine Revolution against Spain.

Among those arrested in the sweeping operations against the Katipunan were 13 prominent citizens of Cavite who were executed by firing squad two weeks after the outbreak of the revolution. The “Trece Martires” or Thirteen Martyrs consisted of businessmen, entrepreneurs, military leaders, a physician and a pharmacist, an educator, a public servant, and even a tailor. All over the islands, scores of other citizens fell under the military might of the Spanish crown, even as poorly armed Katipunan forces began their fight for freedom.

The culmination of the Katipunan uprising was the declaration of independence from Spain on this day 123 years ago. Of course, that independence was short-lived, since even then the United States had already “purchased” the Philippines from Spain and was determined to impose colonial governance on the islands, setting off the bloody Philippine-American War that resulted in the re-colonization of the islands until the end of American rule in 1946.

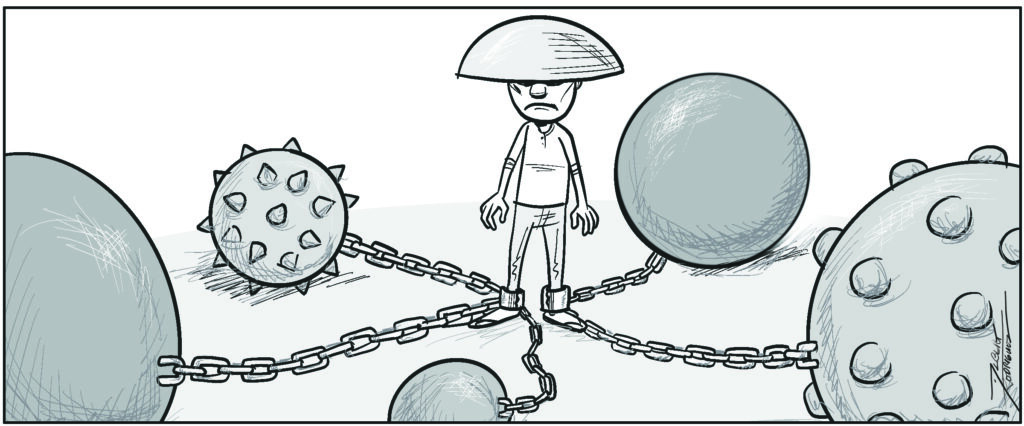

Today, Filipinos are at least nominally independent, or living in an independent republic. And yet, well over a century since that foundational struggle for freedom, Filipinos find themselves grappling with unexpected, if not unprecedented, challenges not just to their quality of life and individual liberties, but also to their sovereignty and territorial integrity. A supposedly “friendly country” flexes its military might to trespass our borders and occupy our islands, exploiting our natural resources and even endangering our food security. But what do our political leaders do? Not only do they hesitate to assert our sovereignty, they also discard hard-won victories in international venues that have recognized our authority over waters and islands within our borders.

Meanwhile, at home, age-old problems continue to plague our people. Majority of Filipinos are brutalized by social inequity, and seemingly never-ending poverty, while rapacious ruling classes and political dynasties exploit the weaknesses in the country’s democratic structures to perpetuate themselves in power.

The everyday indignities and injustices of a fragile, fraying republic have now all been exacerbated by a sweeping public health calamity, where the incompetence of government functionaries and leaders has resulted in growing numbers of the sick and dying and continued vaccine skepticism, while delaying, interminably it seems, economic recovery and a return to some semblance of normalcy and stability. Why have our neighbors managed the pandemic crisis so much better, at much higher levels of efficiency and much lower levels of state repression?

We have long taken pride in our claim of being the first independent republic in Asia. But this boast is empty of any real achievement in terms of bettering the lives of most Filipinos today, who remain hampered by hunger, by lack of opportunity, by an uncertain future.

In June 1898, after the Philippines had wrested its freedom from Spain, Apolinario Mabini issued “The True Decalogue,” where, as sociologist and Inquirer columnist Randy David put it, “he instructed Filipinos on the meaning and responsibilities of citizenship in a modern state.” The “brains of the revolution,” said David, hoped to see his countrymen “confidently assert themselves as free citizens of a republic, rather than live as docile subjects of a monarchy or of a few homegrown political dynasties.”

“Strive for the independence of your country, because you alone can have a real interest in her aggrandizement and ennoblement…,” Mabini wrote. And “Strive that your country be constituted as a republic, and never as a monarchy: a monarchy empowers one or several families and lays the foundation for a dynasty; a republic ennobles and dignifies a country based on reason, it is great because of its freedom, and is made prosperous and brilliant by dint of work.”

All that sacrifice and effort for a truly liberated nation and an enlightened, empowered race: Would Mabini and our other heroes and martyrs be able to say, looking at the current state of the country they had birthed, that it’s all been worth it?