Farmers’ harvests this year are disappointingly smaller than before – not just in amount but in size also of the grains itself.

By MARYA SALAMAT

Bulatlat.com

MANILA – Just last March the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) welcomed a book about climate change impacts on agriculture in the Philippines. It outlines policy recommendations for helping the Philippine agriculture adapt to climate change, as written by the International Food Policy Research Institute. The NEDA has a “collaborative research” partnership with the institute since 2015.

For the Department of Agriculture, meanwhile, responses to climate change this year include pushing the use of hybrid rice seeds, approving the Israeli government’s proposal to fund the building of solar-irrigation systems nationwide and related to this, drafting a National Irrigation Plan.

But all these are still mainly plans. To ordinary peasants from Occidental Mindoro, the Bicol region and Eastern Visayas, immediate relief is what they direly need.

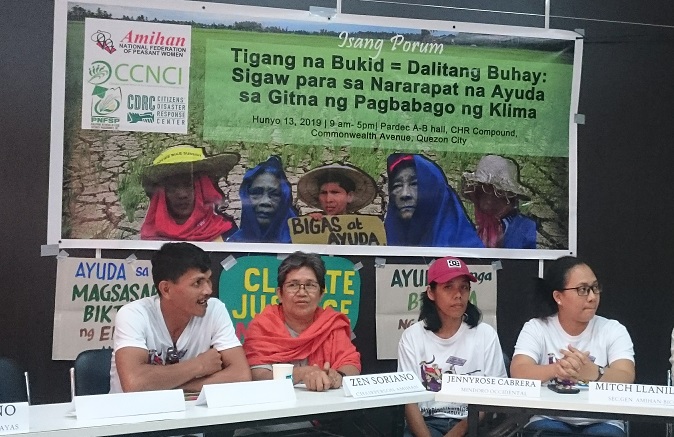

“The government is making noises about El Niño, but it continues to neglect the direct victims, the poor peasants and peasant women, who are at present facing bankruptcy, indebtedness and eventual displacement from their lands,” said Zenaida Soriano, chairperson of Amihan (National Federation of Peasant Women).

The peasant groups have been conducting their own assessment of the impact of climate change on agriculture, particularly the still ongoing drought under the El Niño phenomenon.

There is much the country’s government agencies and local government units have to do in the face of climate change. The first and the most urgent is responding to the demand for relief by farmers hit hard by the typhoons last year then by a severe drought this year, Soriano said.

Based on the latest report of the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council, drought and dry spell damage to agriculture has reached P7.96 billion affecting 247,610 Filipino farmers. It mostly afflicted rice production with losses amounting to P4.04 billion in 144,202 hectares and corn production in 133,007 hectares.

Shrinking palay harvest

Farmers in Bicol and in Occidental Mindoro said they have not yet recovered from the damages brought by typhoon Usman in December last year. Yet, this year, hope of recovery eludes them as their crops reeled from worsening drought.

Farmers’ harvests this year are disappointingly scantier than before – not just in number of sacks but in the size of the grain itself. In some ricefields, farmers grieved over unhusked golden grains of palay that turned out to be either empty of the precious rice inside or the grains are too soft, too crumbly it easily disintegrates before farmers can mill it, dry it or gather it into their sacks.

In the towns of Mamburao and Abra de Ilog, both in Mindoro, the El Niño drought has incinerated the farmers’ palay yield to zero; in Rizal town also in Mindoro, farmers’ yield drastically fell from 50 percent to as much as 80 percent of what they used to harvest. Farmers lament their 21 cavans of palay compared to last year’s 110 cavans. A farmer from Sta. Cruz town in the same province reported a drop in yield by more than half their yield in the previous year. For example, from 61 cavans this March 2019 compared to 137 cavans in March 2018.

During the consultations held by Amihan, Climate Change Network for Community-based Initiatives, Inc. CCNCI and PNFSP from May 29 to June 7, 2019 in the Bicol region and Occidental Mindoro, Bicolano farmers reported agricultural damage reaching P1.1 billion affecting 31,000 farmers in 32, 000 hectares.

The Occidental Mindoro provincial government has declared the province under a state of calamity last April 2019 as damages in agriculture reached P275 million, of which P261 million are in rice lands.

In Eastern Visayas, 15,146 hectares of farmland and 18,187 farmers reeled from the drought.

This is worse than it sounds because according to the Samahan han Gudti nga Parag-uma ha Sinirangan Bisayas (SAGUPA-SB), farmers in the region have not yet recovered from the devastation of typhoon Yolanda followed by crop infestation that destroyed what Yolanda left behind in the region’s major crops such as abaca, palay and coconut.

“We join their call for immediate aid, food and financial assistance, to help them recover from the calamity,” Soriano said last week while waiting for a scheduled dialogue with government agriculture representatives.

The farmers’ groups have been knocking on government agencies’ doors not only for immediate relief but also for the means to help them recover and even improve their agricultural production.

Farmers seek gov’t support

At best, the government has provided only a negligible support to the farmers, Soriano of Amihan said.

“We have to pay for irrigation or worse, bear the skyrocketing costs of gasoline to pump water into our parched, unirrigated ricefields,” a peasant woman from Mindoro recounted during a consultation organized by Amihan at the Commission on Human Rights last week. On the few occasions some local government units tried to help the drought-affected farmers, the aid was too little or too late, said the non-government CCNCI which joined Amihan in consulting with the drought-affected peasant communities.

In Occidental Mindoro, Amihan found that a government official gave 20 liters of gasoline to each of some 200 resident voters at one point during the drought. But it didn’t reach or cover many poor farmers in the area. The CCNCI noted that in some places, deep wells built by local officials failed to benefit the drought-hit farmers.

“Farmers and peasant women’s demand for immediate assistance to ease the burden of drought and high cost of production resulted to petitions and dialogue with local government units,” Soriano said.

In Bicol, farmers under KMB and Amihan managed to get some farm inputs as support from their local government units. But even they admit it is not yet enough to cover all the drought-hit farmers.

Despite billions of budget for disaster response and rehabilitation, all farmers’ groups who participated in the consultation-forum with Amihan and CCNCI bewailed the “failure” of the Department of Agriculture under the Duterte government and the local government units to lay down concrete actions toward mitigating the impact of drought on farmers.

“If not for the farmers’ collective action and active engagement with government units and agencies, the farmers will forever be forced to wait in vain,” Soriano ended.

The post Scant gov’t response to climate change hitting farmers the hardest appeared first on Bulatlat.