“Eleven percent of households in Hong Kong have domestic workers but it seems the HK government and some employers continue to overlook this vital fact in enforcing preventive measures. Most are underfed and overworked.”

By TRINA FEDERIS

Bulatlat.com

HONG KONG – Hong Kong, a highly-developed territory 1,330 kilometers from Manila, is the stuff of middle-class dreams. With its luminous skyscrapers, magical Hong Kong Disneyland theme park, year-long sales, and manageable public transport system, it remains hugely popular with Filipinos, both for tourists and workers.

Majority of the Filipinos who work here are domestic workers. Of the 390,000 migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong, 97 percent are Filipinos. The Philippines’ labor export program, according systematized the enforcement of Filipinos to work abroad., according to Dolores Balladares-Pelaez, chairperson of United Filipinos in Hong Kong (Unifil-Migrante-HK). It is the Hong Kong chapter of MIGRANTE International.

In this fast-paced city, families rely heavily on live-in migrant domestic workers to smoothly run a household. “Domestic workers are required by law to live in the employer’s home. We are expected to do the typical domestic chores such as cleaning the house, shopping for essentials, cooking, washing and ironing of clothes. However, we are also in charge of taking care of our employer’s children and their pets. Some are also involved with elderly care. Working hours here are not regulated, making us overworked. And this is why we take our rest days seriously,” Balladares-Pelaez explained.

One can certainly see what she means by just strolling around posh Central on a fine Sunday. Hong Kong is dense, with every available space put to use; sometimes in multiple ways. This reality is evident in Central on a Sunday, where streets passable to vehicles on weekdays turn into spaces for hanging out for OFWs. This is where Filipinos place flattened cardboard boxes for seats, or beds, if you were so inclined. It is also common to have some groups gyrating to the latest dance craze, a few groups practicing on imagined catwalks, and progressive migrant organizations holding programs or discussion groups, or even meetings, all in just one street.

It is here that Ian spends his Sundays. Ian, an LGBT activist, is usually seen among fellow OFWs explaining burning issues of the day. Here, he and his fellow organization members also perform free health services to domestic workers. “It helps with my homesickness,” he said simply. He was supposed to surprise his mother (and his child) in the Philippines with a visit in mid-February for her birthday, but because of COVID-19, and the subsequent travel ban imposed by the Philippine government, he decided to cancel his trip home.

COVID-19, originating in Wuhan, China, has affected migrant domestic workers in various ways.

The recently-lifted travel ban caused consternation among Filipinos caught unaware. Hastily-declared on February 2, hundreds of OFWs, residents, and students supposed to return to Hong Kong were left scrambling to find ways to return here. According to Balladares-Pelaez, some booked flights to “decoy” countries, before booking their flights to Hong Kong.

But some are not so lucky, as they feared they will no longer have jobs waiting for them after their flights got cancelled. Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA) offered P10,000 (US$197) to every affected OFW, but according to Ian, this is nothing. “I think the P10,000 OWWA is offering was just to appease the swell of anger from affected Filipinos for OWWA’s abrupt announcement. I don’t think P10,000 is enough for those who fear of being terminated because they cannot come back on the planned date. This is our reality, we can be terminated even for the flimsiest of reasons.”

Amy, a leader of Association of Concerned Filipinos in Hong Kong, was also supposed to fly back home to reunite with her college best friend whom she has not seen for the past 18 years. Her friend offered to pay for her airfare, but due to the travel ban, they delayed their reunion. “I told her the quarantine will be 14 days. If I go on with the trip, I will be stuck in isolation for two weeks. That will use up my whole vacation, so what’s the point? She also said she cannot book any flight for me, because of the ban,” Amy said.

Amy recounted that weeks into the virus outbreak, some HK resident resorted to panic-buying. “Those days, I went to the market every day, sometimes twice a day, because I could not complete my grocery list. At that time, surgical masks, toilet paper, disinfectant liquid, antibacterial hand soap, rice, and noodles were hot items. I joined long lines, hoping that I will be able to get what I need, but sometimes the store runs out before my turn. So I usually end up sleeping later than usual just to scour around for supplies. My employer also asked me to take a bath every time I return home. It got to the point I was already getting colds due to this regimen, so I asked my employer if I may go out only once a day. After all, I still have to disinfect the whole house every day, aside from my usual duties.”

Some migrants choose to stay at home on their rest day due to pre-existing conditions . Lai, who has a history of asthma and pneumonia, has been refrained from going out. Even as she needs to continue her therapy and treatment for her soft tissue injury, her employer deemed it necessary to cancel the succeeding appointments. She said her family is worried due to her weak immune system and they want her to come home. “But I know I will die early if I do that, given my condition wherein I have to see the doctor every month. At least here, healthcare is excellent and free.”

Like Lai, Bing, a unionist, also has health problems prior to the current epidemic. “My family back home worries about me. I have hypertension, and because it’s winter, I have been a victim of flu twice over. This has limited my time outside. Instead of being with my fellow unionists, I stay at my employer’s house worrying about my usual Sunday tasks.”

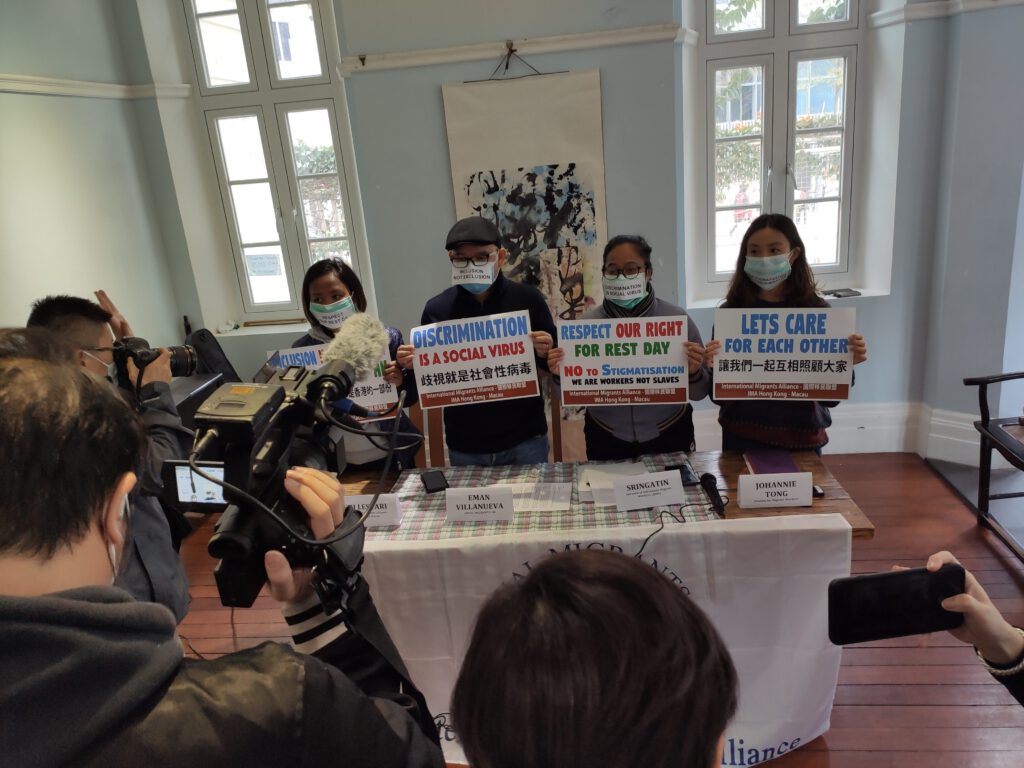

Discrimination is a social virus

Still, OFWs are treated as second-class citizens, Balladares-Pelaez said. “Discrimination against migrant domestic workers is even more evident during crises such as this epidemic. Health announcements are in languages not commonly understood by majority of domestic workers,” she said.

Recently, a Filipina domestic worker who has never been to Wuhan, tested positive with the virus. UNIFIL, along with other migrant organizations, have been tirelessly campaigning since Day 1 of the epidemic to not exclude domestic workers from protective measures and medical treatment.

“Eleven percent of households in Hong Kong have domestic workers but it seems the HK government and some employers continue to overlook this vital fact in enforcing preventive measures. Most are underfed and overworked,” Balladares-Pelaez said.

In its 2018 Annual Service Report, Mission For Migrant Workers reported that 99 per cent of its service users had long working hours, with 56 percent working for 11 to 16 hours, while 43 percent worked for more than 16 hours per day.

Balladares-Pelaez then recounted that Hong Kong’s Labour Department (LD) even suggested that domestic workers refrain from taking their days off to avoid getting sick. “The LD perhaps forgets that any suggestion coming from them can be misconstrued as a directive. And it has been taken as such by employers who are fearful that the workers will get sick during their rest day. It’s not as if the virus only spreads during Sundays. Not to mention that the rest of the household can come and go as they please.”

Ian was actually forbidden by his employer to go out at night after work following news that broke out of a confirmed case near their place. He was also asked by his employer to stay home on Sundays. “I explained that I might not die because of the virus if I stay home, but I will die of boredom, homesickness, and sheer exhaustion. I also said that the request reeks of discrimination because I am still asked to go to the market during weekdays.”

Amy shared that her employer wanted to restrict her activities during Sundays, but she refuses to back down because she knows her rights. “My employer saw me holding a placard once because they usually visit a nearby library on Sundays. He said that he knows I’m an activist and that is why I am always arguing with him. I just know that I have to fight for my rights.”

She continued to recall the time her employer told her that she will not die if she does not eat for a day. “I told him he should try it to see how it feels like. Due to my insistence, he eventually gave me food allowance. And now, I am included in the allotment for supplies, such as alcohol and vitamins. ”

Worried families

Worrying is such an unpleasant activity, yet one cannot help but indulge in it when a loved one is overseas. OFWs also worry over their families back home, but as Bing said, one needs to toughen up to be able to overcome this. “I have to take care of myself to lessen their anxiousness.”

“Oh yes, my family is worried,” Amy shares. “They know I can be fearful, yet have the tendency to hide it from them. I just reply every time they send me messages and call them every day. also assure them that I know the precautions, such as wearing a mask every time I go out, etc.”

“During these times, it is important to not be overcome by fear,” Ian said. “To steel myself, I remember my dreams for my child . It also helps to talk to loved ones, and to feel their support. We in the organization also help each other through these tough times. We inform ourselves of the necessary precautions, as well as what to do when we feel ill.” ”

Despite these difficulties, OFWs like Ian choose to continue to work here. “I tell my mom that if I get sick here and I die, I will be the only one who dies in our family; but if I go home, all three of us will die . I say it in jest, of course. But it can actually happen because of how expensive the basic needs are in the Philippines. It’s also another matter if I can find work there; even if I do, I know the salary will not be enough to sustain our daily needs, along with my mother’s medical needs.”

For all its bright lights and nice sights, Hong Kong remains to be a dream destination for Filipinos. For OFWs in Hong Kong however, they dream of being together with their families back home. But here, the cold space in their lonely hearts continues to fill up with warm memories and plans of shared struggles. And for some, this is enough to sustain the long dark nights in this season of illness.

The post Season of illness appeared first on Bulatlat.