His spokesperson Salvador Panelo insisted that it wasn’t because President Rodrigo Duterte thinks that the 1986 civilian-military mutiny at EDSA isn’t important; it’s just that he has a lot of things to do.

Panelo announced Mr. Duterte’s non-attendance at the February 25 official commemoration of the 33rd anniversary of that event days earlier. That made the claim that “he has a lot of things to do” sound like one more lame excuse in the Palace’s lengthening list of such other excuses as “he was tired,” to explain his absence in a meeting of ASEAN heads of states; that he was “resting” during the three days he didn’t attend any official function; or that he suddenly flew to Hong Kong “to go shopping.” But what made it really look like a deliberate snub is that he has never graced that occasion, his failure to do so this year being his third since 2017.

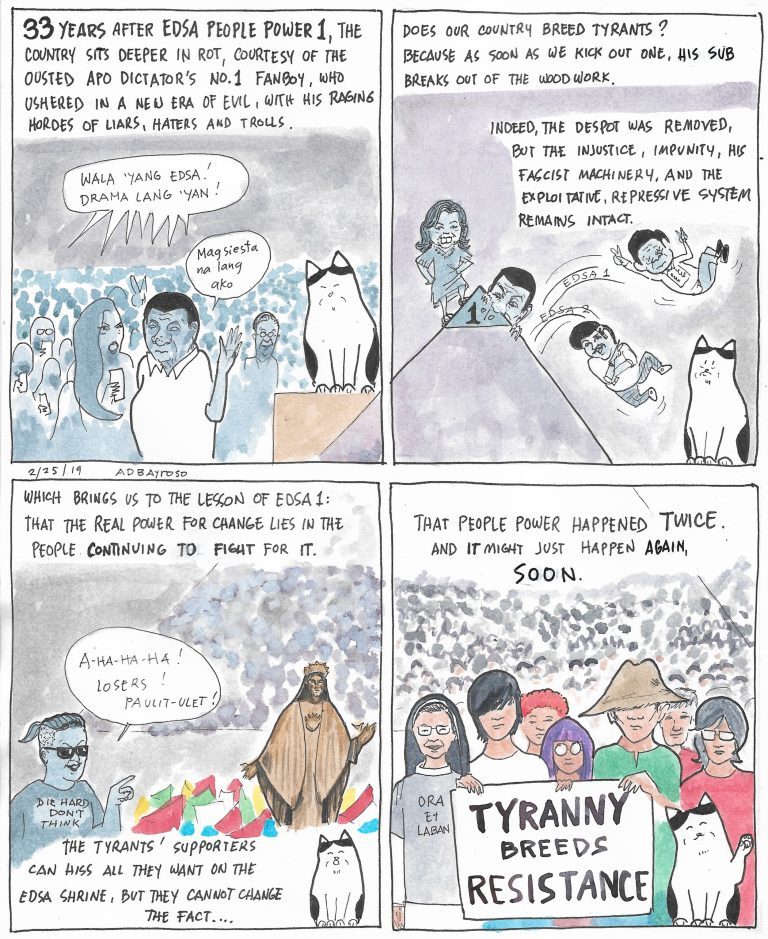

One can only conclude that Mr. Duterte has a dim view of the February 22-25 events at EDSA, most probably because they led to the overthrow of the Marcos kleptocracy. Like his mercenary keyboard army of trolls and hacks in print and broadcast, he probably thinks that only the Aquinos gained anything from EDSA 1, and that it removed from power a decisive man of action whose clever use of the police and military to advance his and his family’s political and economic interests deserves emulation rather than history’s condemnation.

Mr. Duterte has not only expressed his admiration for this country’s first and hopefully last tin-horn version of Adolf Hitler (whose “decisiveness” in murdering six million Jews he once admitted he admires). He has also demonstrated it in at least three ways. There was his decision to allow the burial of the earthly remains of the far from heroic Ferdinand Marcos, Sr. in the country’s Libingan ng mga Bayani. (Heroes’ Cemetery). There is also his ill-concealed support for Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr.’s electoral protest. Add to that his outright declaration that despite the Constitution, he prefers Marcos, Jr. over Vice-President Leni Robredo to succeed him should he resign the presidency.

To explain Mr. Duterte’s unashamed pandering to Marcos interests, some observers say it’s because Ilocos Norte Governor Imee Marcos, who’s currently running for senator, was one of the few local government officials to support his candidacy for president of this unfortunate Republic. But it’s likely to be due not only to the Marcoses’ financial and other forms of support in 2016. What’s even more disturbing is that it might be because of his own belief that he’s entitled to the same unaccountable abuse of power that Marcos exercised by declaring martial law in 1972.

Once a petty provincial despot whose powers were so unchecked they included, by his own admission, support for, if not command over a death squad, Mr. Duterte has since demonstrated his contempt for the system of checks and balances mandated by the Constitution as well as for free expression and the independent press vital to democratic governance.

As distressing as that may already be, the opinion polls have since found that many Filipinos share, if not Mr. Duterte’s sense of entitlement, at least his fascination with dictatorship as the path to the solution of this country’s legions of problems.

That fascination is founded as much on the obvious failures of what passes for democracy in these isles of illusions as on the far too common and totally baseless, fact-challenged belief that the Marcos dictatorship was a period of peace and prosperity.

By encouraging EDSA 1’s being labeled a “revolution,” with all the promise in that description of political and economic democratization and of ending the poverty, social inequality and mass misery that have long haunted this country’s long-suffering people, the leading figures of EDSA 1 — Corazon Aquino, Jaime Cardinal Sin, Fidel Ramos, Juan Ponce Enrile — were at least partly responsible for the perception that what had replaced the Marcos tyranny was democratic rule.

It was no such thing. EDSA 1 made possible the return to power of the wing of the political class that Marcos had targeted for exclusion through Presidential Decree 1081. It reestablished the limited, elite democracy that had been in place since Commonwealth days, rather than install a government run by the majority. EDSA enabled the land-based faction of the ruling political elite to overthrow one-man rule, and to repeal Marcos’s most repressive laws. Both were necessary for the country to move forward, but that was about all it did.

Restored by EDSA 1, the rule of the land-based, old-rich was saddled with such remnants of the past regime as Enrile and Ramos, who eventually gained even more power and in fact allowed the return of the Marcoses and their allies not only to the country in a literal sense, but also to government.

Not only in the ensuing years after EDSA 1 were the promises of that “revolution” unfulfilled. Very early on, for example, despite such sound advice as that of the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Roy Prosterman for President Corazon Cojuangco Aquino to use her legislative powers to decisively address the land issue before Congress reconvened, or else risk civil war, the latter balked and relied on the landlord-dominated Congress to later pass a land reform law so full of loopholes it became practically meaningless.

Mrs. Aquino’s reluctance to outrightly abolish the Philippines’ centuries-old land tenancy system — “the worst on the planet,” according to Prosterman — wasn’t entirely due to her fears of abusing her pre-1987 “revolutionary” powers. Subsequent versions of land reform allowed the conversion of agricultural lands into industrial estates, which is what the Cojuangcos did to their own Hacienda Luisita.

The twin imperatives of authentic land reform and industrial development — policies at the heart of the development of Japan, China, Korea, Taiwan among others — succeeding regimes belittled and ignored, and at one point even described (during the Benigno Aquino III administration) as “old hat.” Instead, it is the decades-long policy of encouraging foreign investments that has remained in place despite its demonstrated shortcomings.

The consequences are there for all to see: the persistence of poverty and hunger despite economic growth and, consequently, the desperate search for a solution among the country’s impoverished and powerless millions. Every election period, they are nevertheless deceived into electing to office the same dynasts and their allies whose only program is to advance their self, familial and class interests and to kowtow to whatever foreign power is willing to support their continuing dominance over the politics and government of this neo-colony..

What is outrageous is that it is those very dynasts who are responsible for the country’s being the basket case of Southeast Asia. Their incompetent, corrupt, and self-aggrandizing governance has been a total failure. But they blame the democracy they’ve been sabotaging for decades for the consequences of their benighted rule..

EDSA 1’s failure to deliver on its implicit promises of peace, prosperity, freedom, independence and democracy, for which the political dynasties are as responsible, does not justify the return of another dictatorship. But it is nevertheless another fallacy the hucksters and demagogues in and out of government are currently selling in their attempt to excuse the country’s descent into another tyranny.

Luis V. Teodoro is on Facebook and Twitter (@luisteodoro).

www.luisteodoro.com

Published in Business World

Feb. 28, 2019

The post Blaming EDSA appeared first on Bulatlat.