By Catalina Ricci S. Madarang – December 21, 2020, Philstar.com/Interaksyon

Calls to end police brutality dominated conversations online on Monday after a cop was caught in a viral video killing an unarmed mother and son in Paniqui, Tarlac.

Police officer later identified as Senior Master Sergeant Jonel Nuezca on Sunday shot 52-year-old Sonya Gregorio and her son, Frank Anthony Gregorio, 25, over an altercation regarding the latter’s use of “boga,” an improvised noisemaker used during the holidays in the Philippines.

Nuezca, who was reportedly assigned to the Parañaque City Crime laboratory, surrendered at the Rosales Pangasinan Municipal Police Station an hour after the incident.

He also turned over his PNP-issued 9mm semi-auto pistol that was used in the crime.

In an interview with GMA News’ “Unang Balita,” Police Lieutenant Colonel Noriel Rombaoa, chief of the Paniqui Police, said that the suspect went to the victims’ houses to confront them.

“Pumunta yung police sa bahay ng biktima at nagkaroon ng pagtatalo, naungkat ang matagal na nilang alitan sa right-of-way,” he said.

Nuezca refused to say anything except he regrets shooting the two victims, Rombaoa added. He also stated that the former will face a double murder complaint from the local police.

Data from Police Regional Office III chief Police Brigadier General Val de Leon showed that Nuezca had faced grave misconduct or homicide cases in May and December last year. However, these cases were dismissed due to lack of substantial evidence.

Nuezca had faced grave misconduct (homicide) cases in May and December 2019. Both, however, were dismissed due to lack of substantial evidence.

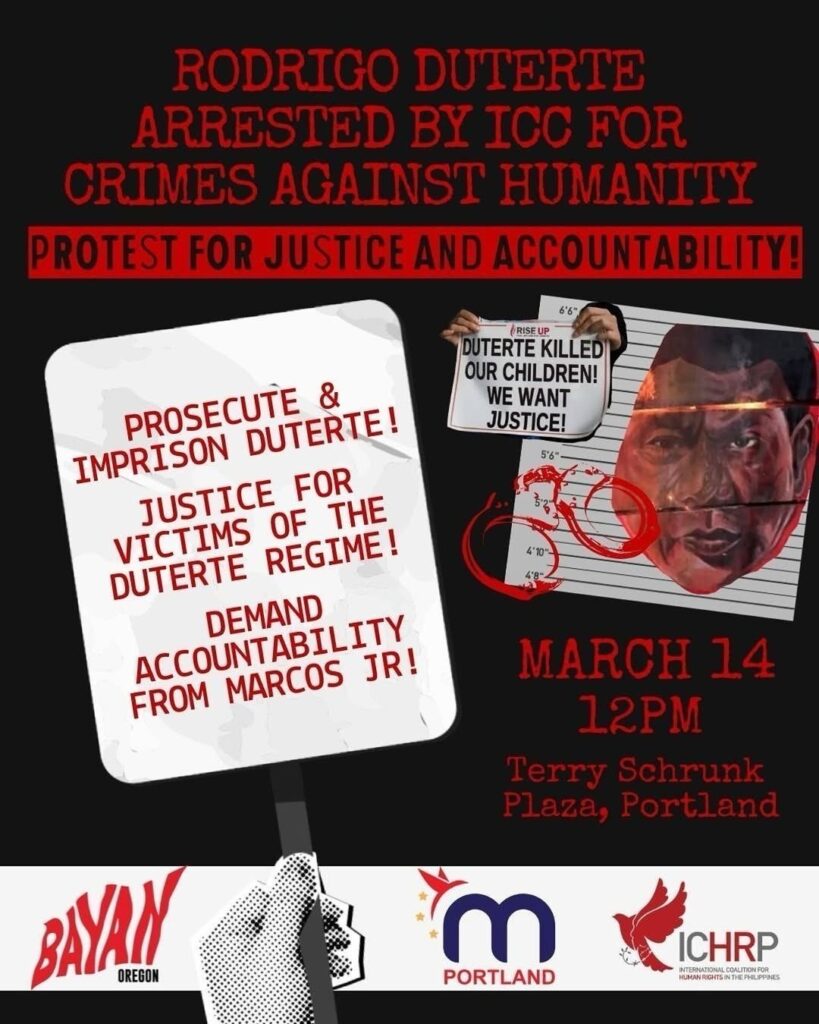

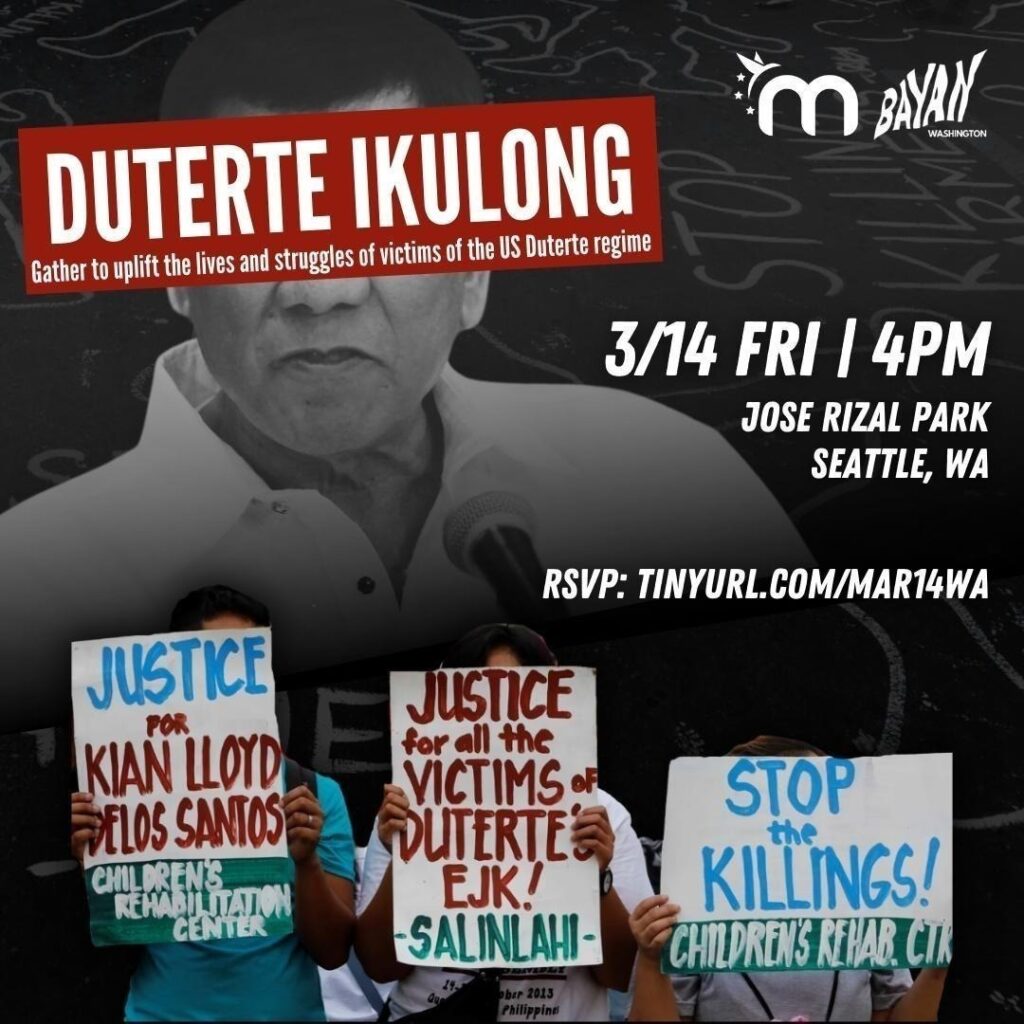

Stop the killings

Several hashtags and the phrase “My father is a policeman”

dominated the top five spots on Twitter Philippines’ trending list on Monday as concerned Filipinos and human rights advocates called to end police brutality in the Philippines.

The phrase was uttered by the daughter of Nuezca during the altercation between the victims and her policeman father, seconds before the Gregorios were shot dead.

Nuezca’s daughter also received backlash online for this remark. Twitter user @lakwatsarah, said that the daughter might have been raised to believe that her father is above the law.

“She was probably raised to believe he can shoot anyone who messes with them. He shot them. He made that choice. The daughter is a victim of his parenting,” she said.

Aside from this phrase, the hashtags in the local Twitter’s top trending list as of writing are:

- #StopTheKillingsPH with over 670,000 tweets

- #JusticeforSonyaGregoria with over 360,000 tweets

- #EndPoliceBrutality with over 286,000 tweets

- #Pulisangterorista with over 191,000 tweets

The calls for justice for Sonya and Frank Gregorio were also launched on Facebook.

Progressive groups such as the League of Filipino Students and Gabriela Youth issued separate statements that denounced Nuezca’s brutal act and other cases of abuse and killings in the Philippines.

‘How many were not filmed?’

Meanwhile, Interior Secretary Eduardo Año said that the shooting incident in Paniqui is an “isolated incident.” He also said that “the sin of Nuezca is not the sin of the entire Philippine National Police.”

“This is an unfortunate but isolated incident. While there are unfortunate incidents like this, the vast majority of our PNP personnel perform their sworn duties everyday with honor and integrity to protect and serve the people,” Año said.

Writers Emiliana Kampilan or “Dead Balagtas” and Alfonso Manalastas, however, noted the possible deaths at the hands of the police and the military that were not caught on camera.

Bar 2019 topnotcher Kenneth Manuel echoed the similar view and questioned if there were more underreported victims.

“Minsan mapapaisip ka na lang, ilan na kaya nakitil nito pero hindi lang naibalita? Mas mapapaisip ka, ilan kaya sa kanila ang kayang pumatay ng ganito?” Manuel wrote.

Several concerned Filipinos also questioned this possibility, while citing that drug suspects were killed before because they allegedly fought back or “nanlaban” but there were no videos to prove them.

Detained Sen. Leila De Lima in 2018 called out the government and former presidential spokesperson Salvador Panelo for using the “nanlaban” narrative.

“I cannot allow Panelo to continue to poison the public’s mind with the Duterte administration’s oft-repeated but flawed proposition that the increasing number of deaths due to the crackdown on drugs was because suspected drug offenders have all resisted police arrest with violence,” she said in December 2018.

Meanwhile, others lamented the Christmas bonuses police officers received despite the reported brutality.

“Tapos mas mataas ang bonus ng mga pulis kaysa health workers?” he said.

Not the first time

Data from World Population Review showed that in 2020, the Philippines ranked third among the countries with the highest cases of police killings wherein 3,451 people were killed or a rate of 322 victims per 10 million people.

In a September report from US-based Human Rights Watch, citing government data, the PNP killed 50% more people between April and July of this year despite the ongoing novel coronavirus pandemic.

HRW noted that this figure is only for deaths in police anti-drug operations.

Last June, the rising cases of police abuse in the Philippines which happened before and during the pandemic were juxtaposed to the killings perpetrated by the police in the United States.

The death of George Floyd, a 46-year-old black American who was killed by a police officer in Minneapolis triggered a nationwide campaign for equal rights for all people of color.

RELATED: ‘I can’t breathe!,’ ‘Tama na po’: Police brutality in US, Philippines juxtaposed

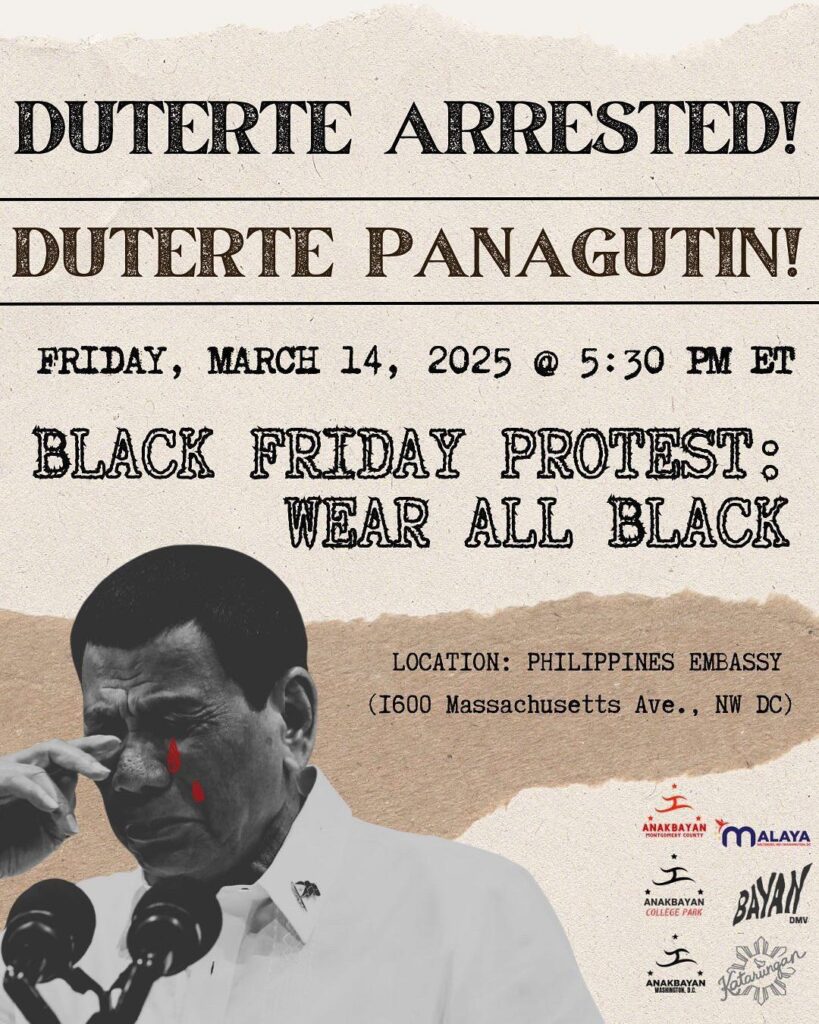

Duterte’s ‘shoot-to-kill’ remarks

Some Filipinos blamed such rogue activities among PNP members on President Rodrigo Duterte’s continuous “shoot-to-kill” remarks since he took office in 2016.

In a televised address aired last December 16, Duterte denied ordering the police to “shoot to kill” civilians.

“May mga pulis na talagang may ano sa — diretso salvage ganoon. Wala akong inutos na ganoon. Remember, in all of my utterances, ang galit ko ‘yan when I say, ‘Do not destroy my country, the Republic of the Philippines, who elected me as President. Do not destroy our sons and daughters because I will kill you.’ Sabi ko — hindi ko sinabi, ‘They impede, they will kill you.’ The military will… I said, ‘I will kill you,’” the said.

“Pero sabi ko, ito, ‘Go out and destroy the apparatus.’ Iyan. Pagka nagkabarilan diyan in destroying the apparatus, goodbye ka. Kaya sabi ko, ‘Ako, I take full responsibility for my order.’ ‘But remember,’ I said, ‘enforce the law in accordance with what you have learned then self-defense.’ Defense of ano ‘yan. Stranger kung kasama mo. In law it’s called a stranger, maski kilala mo. Defense of relative,” he also said.

‘Walk the talk’

Amid the outrage on Nuezca’s brutal act both Paniqui Police chief Rombaoa and PNP chief Police General Major Debold Sinas reminded their colleagues to observe “maximum tolerance.”

“Sa mga kasamahan po natin sa pulisya, dapat self-control kasi nga maximum tolerance tayo, tayo ang may armas. Kung merong umaagrabiyado sa atin merong right forum po riyan, pwede nating kasuhan, not to the point na gagamitin natin ang baril natin,” Rombaoa was quoted as saying.“Lagi nating tandaan ang ating sinumpaang tungkulin bilang tagapagpatupad ng batas. We should walk the talk in the PNP,” Sinas said. #