Feb 11, 2018, Rappler.Com

Understanding that fake news is the professional product of advertising and PR strategists means we need to challenge the broader system that has not only normalized political deception but made it financially rewarding.

While the Philippine public’s moral panics about fake news focus on notorious celebrity influencers such as Mocha Uson and their avid followers – derogatorily dubbed as “troll armies” – our latest research funded by the British Council reveals that the real chief architects of disinformation wear respectable faces as leaders in the ad and PR industry, hiding in plain sight while sidestepping accountability.

In a 12-month project conducted by researchers in the University of Massachusetts, University of Leeds and De La Salle University Philippines, we conducted in-depth interviews and online observation with operators of fake Facebook and Twitter accounts, and the strategists who provide them the detailed scripts and schedules to follow.

We gained unprecedented access to the digital underground, with informants supplying us with passwords of fake accounts used to seed divisive memes and revisionist history narratives in the lead-up to the 2016 Philippine elections up to this day.

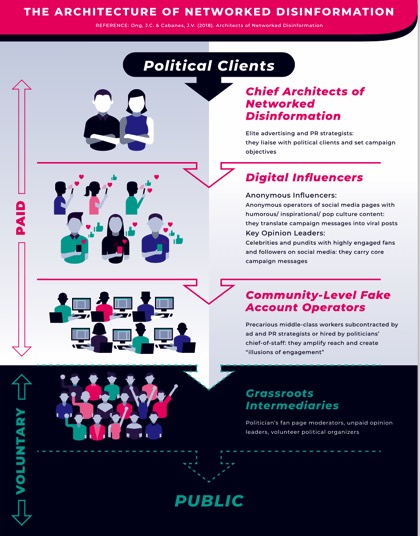

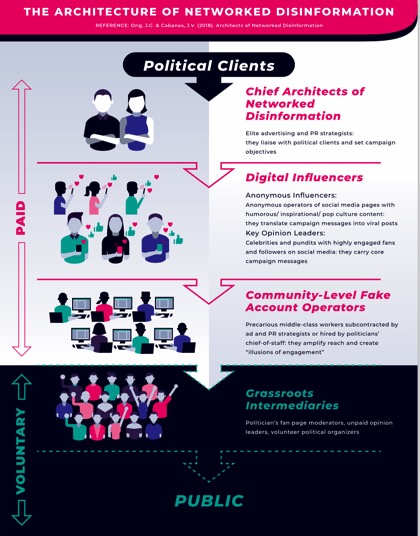

We found that disinformation production is a professionalized enterprise: hierarchical in its organization, strategic in its outlook and expertise, and exploitative in its morality and ethics.

Our report, “Architects of Networked Disinformation: Behind the Scenes of Troll Accounts and Fake News Production in the Philippines”, thus argues that the problem of fake news and disinformation production goes much deeper than exceptional, individual villains. Addressing the problem means challenging the system that has not only normalized political deception, but made it financially rewarding – especially for people at the top.

Ad and PR strategists as chief architects

Occupying the top level of the networked disinformation hierarchy, ad and PR executives play the role of high-level digital strategists. They hold leadership roles in “boutique agencies”, handling a portfolio of corporate brands while freelancing for political clients on the side.

Motivated by the challenge of proving their clout in a new political and professional arena, “chief disinformation architects” use professional tools of the trade to fulfill their political clients’ needs. With their track record for launching Facebook business pages, trending hashtag campaigns worldwide, and building engaged communities for household brands, telcos or celebrities, tried-and-tested industry techniques of spin and reputation-building acquire new power and momentum in their hands – and these skills are for sale.

To quote one of the strategists we interviewed: “The only difference is that you’re a high-class prostitute in advertising, but in political marketing you’re a low-class prostitute.”

“Brand bibles” and “campaign objectives” in hand, chief architects of disinformation then assemble teams of anonymous digital influencers and fake account operators, on whom they rely heavily to execute their disinformation designs on social media.

Anonymous digital influencers gaming trending topics

Bridging the gap from strategy to the streets, anonymous digital influencers usually operate one or more Facebook pages or Twitter feeds that have anywhere from 50,000 to two million followers.

Their purpose: to hack attention with a specific brand of humor, widely appealing “inspirational” quotes, or astute knowledge of pop culture – and slip in the occasional undisclosed paid post into their feed. They are crucial agents who amplify and reinforce the core communication messages set by the high-profile bloggers and influencers we refer to as “key opinion leaders” in our report.

Hiding behind colorful social media personas, anonymous digital influencers have their fingers on the public pulse, from social media behaviors to political sentiments. Translating campaign strategies into shareable content, they post content for or against particular politicians, often anchored on a hashtag set by the chief architects. They use these to create viral Facebook posts, game Twitter trending rankings, and influence the way mainstream media covers a story.

They work part-time and per project, alongside day jobs in IT, corporate marketing, or online community management for celebrities’ fan clubs. They are the Philippines’ precarious, aspirational middle-class, taking on freelance digital work to achieve a certain kind of lifestyle. They are an organized, skilled, and digitally savvy labor force, or as one chief strategist describes them: “a stockpile of digital weapons” that the Philippines isn’t aware of.

Fake account operators creating illusions of engagement

At the bottom of the hierarchy, community-level fake account operators do what we call script-based disinformation work – the grunt work. Fake accounts post pre-made content on schedule and actively like and share posts to meet a daily quota. More importantly, they create the illusion of engagement – a bandwagon effect that affirms and amplifies the key messages of a political campaign, and encourages real people (i.e., unpaid grassroots supporters and political fans) to openly express their support for a particular politician.

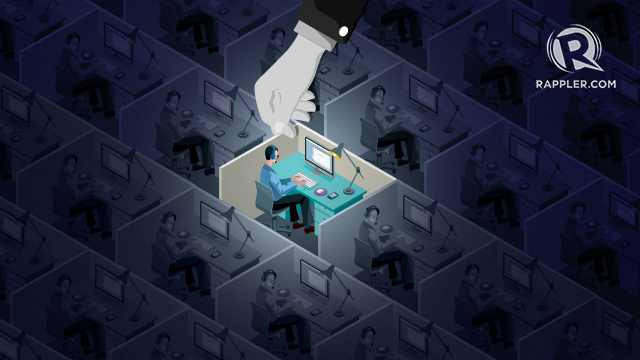

Most of the fake account operators we met were in it for the financial rewards – freelancers paid on a daily basis for hitting their quota of social media activity, or who worked in “call-center” type arrangements in the politician’s hometown. Others were junior employees of politicians’ own administrative staff, assigned to operate fake accounts off hours – work that they did not expect and were not paid extra for.

Understanding and challenging the system

Understanding that fake news is the outcome of a professional and hierarchical work structure rooted in the promotional industries of advertising and PR tells us that we need to be more creative and collaborative in addressing our current toxic climate of information pollution.

While media and civil society initiatives to blacklist fake news websites, expose fake accounts, and fact-check the divisive celebrity influencers may be well-meaning, they do not treat the underlying causes of the problem.

It’s an open industry secret that ad and PR executives take on political sideline jobs. How can their industry peers hold them accountable for the impact of their actions? The development of a self-regulatory commission that requires disclosure of political consultancies is a step towards encouraging the traceability and accountability of these digital campaigns within the ad and PR industry.

New national campaign finance legislation – what we call a Political Campaign Transparency Act – to finally get a clear picture of what politicians spend on digital campaigning is what we strongly recommend. During elections for example, politicians are required to disclose campaign spends on traditional media like TV and radio, but not for online and social media. The public has the right to know the quantity and quality of politicians’ television and radio advertising materials but also the viral videos, trending hashtags, and Facebook advertisements they purchase.

We encourage journalists, civil society leaders, and academics to go beyond selectively shaming notorious influencers and exposing troll accounts while conferring hero status on others.

Beyond high-profile targets, we need to collaborate toward solving the bigger problem at hand: “paid troll” work is an offer that has simply become too good to refuse. While addressing the top of the fake news production hierarchy, we also need to look out for the precarious creative workers who might sign up for this kind of morally questionable work, by creating industry sanctions and safety nets that prevent them from slipping into the digital underground.

To quote one of the “chief architects” that we interviewed: “Every time you see a comment, a post, and everything else, don’t just see a screen. There’s someone warm behind that screen, who’s looking for empathy, who’s looking for a solution, for understanding.”

We hope to have helped open a discussion by attempting to understand the people behind the screen: who they are, how they operate, what motivates them, and what affects the content and narratives they spread. Now, we pass the challenge on to the Filipino public – because the stories they shape may become our own. – Rappler.com

Jonathan Corpus Ong is Associate Professor in Global Digital Media at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst (USA). He is the Convenor of the Newton Tech4Dev Network and author of the book The Poverty of Television: Mediating Suffering in Class-Divided Philippines (2015). Jason Cabañes is Lecturer in International Communication at the University of Leeds (UK). As part of the British Council funded Newton Tech4Dev Network, he co-leads the digital labor research stream.

The report is available for free download at Newton Tech4Dev Network.