“As a health worker, it pains me that my brother has died from this virus. I work hard, look after my patients and even say a prayer for them, because I know the world will turn in my favor one day. But it hasn’t. My brother was neglected.”

By JANESS ANN J. ELLAO

Bulatlat.com

MANILA – “Are you making rags?”

Jejelyn Green Suerte earlier asked his brother, Judynn Bonn, who was busy cutting and sewing fabric in the midst of a pandemic. She is used to seeing his brother looking after things at home.

A scene like this would not have been anything extraordinary. But to her surprise, her brother responded, “I am making a face mask.”

As a medical technologist, she knew of the dangers that health workers are confronting in the face of a deadly virus. She berated her brother that he should be using a proper medical-grade mask, along with a corresponding protective gear during hospital duties. Bonn, on the other hand, assured his sister he would only use it in case proper face masks have run out.

Months later, he tested positive to the COVID-19 virus. And in less than a week, Bonn died.

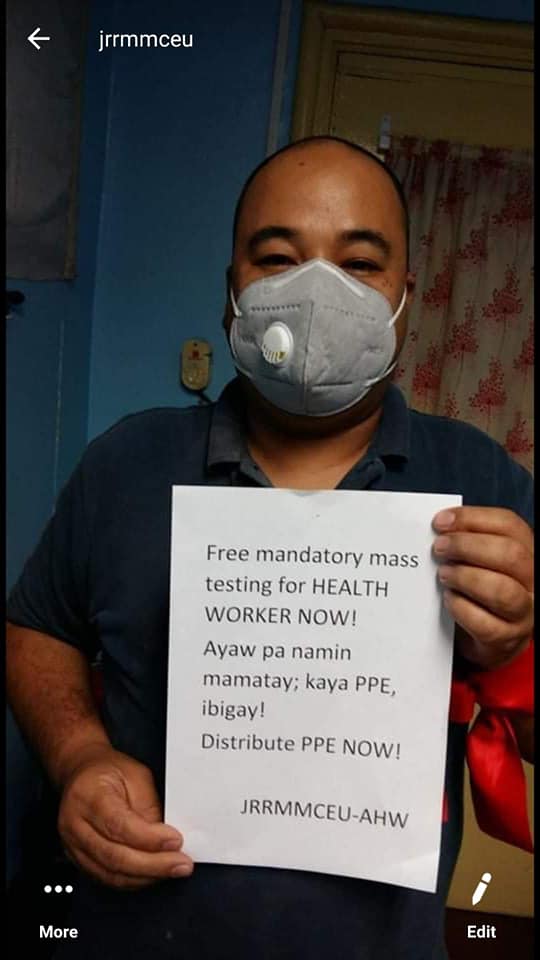

Bonn, a tireless union leader in the Jose Reyes Memorial Medical Center (JRRMC) in Manila, is among the 20 health workers who was

afflicted by the deadly virus. Ironically, he was among those who demanded the provision of personal protective equipment and regular swab tests for their ranks.

The Philippines has one of the highest cases of COVID-19 infections among health workers. Apart from shortage in protective gears, health workers here have long been working for long hours due to chronic understaffing. As it stands, the country, too, has surpassed the 100,000-mark of confirmed COVID-19 cases, the highest in Southeast Asia, and beating even China’s.

“As a health worker, it pains me that my brother has died from this virus. I work hard, look after my patients and even say a prayer for them, because I know the world will turn in my favor one day. But it hasn’t. My brother was neglected,” she told Bulatlat in Filipino.

‘A good brother’

Bonn was a caring and generous brother.

Growing up together in Iloilo and their parents both working, Bonn and Green knew how to look after themselves even at an early age.

But like any siblings, they had their own share of petty fights. With only a two-year gap, they endlessly bickered over who should wash the dishes and do other household chores. Still, Green and Bonn were inseparable. They slept next to each other as kids, and Bonn was frequently irate whenever Green would bother him at night, or when he was writing or sketching.

They always had each other’s back. These include being her escort when she joined a local beauty pageant and even staying within a safe distance whenever Green was caught in a fight.

One time, she recalled, a male classmate tried to enter the fight scene just when Green was winning.

“And he ended up fighting himself,” she said in jest.

Still, she described her brother’s teenage years as “boring.” This, she said, was often a butt of jokes among their cousins. After school, he would go home immediately, clean their house, and cook for them.

With a year and half to go before finishing her college degree, Green was supposed to stop attending school due to financial constraints. But her brother stepped in and provided for her until she finished her medical technology degree.

Both Green and Bonn became health workers. While Bonn finished a computer degree at a local college in Iloilo, he ended up taking up a job at the Jose Reyes Memorial Medical Center.

“We grew up knowing that we can unequivocally depend on each other, without expecting anything in return,” she said.

A family man

Bonn was a family man.

“His family had always been his first priority. He would take the risk of being late for an appointment just to send his children to school,” Green told Bulatlat, adding that she now worries for the future of her brother’s three children and their future, especially his eldest 17-year-old daughter who dreams of being a doctor someday.

At home, her brother would always consult with wife Tess in their decisions. He would always see to it, she said, that they “were

partners in life.”

Josephine Aligano, a colleague of Bonn and a friend to the Suerte family, said they would always tease Bonn for being late. He would also frequently tag his youngest son to union meetings and rallies.

“Oh, dala mo na naman ang buong bahay niyo!” his colleagues would often tell him. (Literally, ‘are you carrying your entire house?’)

Even after having his own family, Green said Bonn continued on being a good son that he was. After long hours of work, he would still find the energy to accompany their mother in the hospital.

‘A reliable colleague’

When Bonn eventually became active in the health workers union, Green was surprised. She thought how could someone who grew up to be a quiet person suddenly found the courage to speak out publicly.

But for his colleagues in the state-run hospital, Bonn was a friendly face, who would always smile and help his fellow health workers who were in need. If you ask him for a favor, both big and small, he is quick to retort: “ako ang bahala dyan” (I will take care of it) with a sweet Ilonggo accent to it.

Aligano said they were worried when they learned that Bonn tested positive for COVID-19. They sent him messages of support while he was still in the hospital to boost his spirits.

“I spoke to him a week before he was swabbed. He looked so healthy. But when he was diagnosed that he had pneumonia, his health

deteriorated fast, it seemed,” she said.

One morning, before Bonn was transferred to a COVID-19 hospital, she sent him soup to make him feel better.

His passing had affected their mood in the hospital, Aligano said, mostly in disbelief of the gross neglect that Bonn experienced just because he was an ordinary mortal. “What if this happened to us? Are we going to suffer the same fate?” she asked.

Government neglect

The employees union at the Jose Reyes Memorial Medical Center, an affliate of the Alliance for Health Workers, blamed the “gross neglect and inefficiency” of the hospital management, the health department and the Duterte administration for Bonn’s death. They are now anxious over their worsening health and working conditions, with infection among health workers increasing.

From day one, health advocates such as the AHW have been pushing for mass testing and the provision of personal protective equipment for health workers.

In a statement, union president Cristy Donguines said the hospital management “blindly implemented” the health department’s protocol that employees who are considered as severe COVID-19 cases should be transferred to any designated COVID-19 referral hospitals.

They are also not provided with due swab tests. Donguines said they are forced to cough up funds in swab testing facilities outside the hospital, amounting anywhere between 1,600 to P5,500.

Her brother’s death, she said, would have been easier to accept, “if we know that all efforts were exerted.”

“We want justice,” she said, “This is why we are speaking out. We do not want other health workers to suffer the same fate as he did.”

Continuing Bonn’s fight

As a health worker in a private hospital, Green said they, too, are overwhelmed with the spike of cases they are receiving. She was not surprised that doctors recently went to public to ask for a “timeout,” among other demands.

“Teka lang ha,” (Give us a second) she told Bulatlat.

She clarified that health workers are one with the government in putting an end to the COVID-19 pandemic. “If we have demands, it is

not just for us. But for the people’s best interest,” she added.

The AHW said that while they are grieving, “we are not losing the strength and fighting spirit to continue the fight of our fellow health workers. Bonn’s calls and struggles are our fight as health workers.”

The post Health worker who died of COVID-19 was a good brother, reliable colleague appeared first on Bulatlat.