An official of the Southern Philippine Medical Center in a statement refuted claims that the hospital is engaged in anomalies on the use of the P326 million reimbursement from PhilHealth for Covid-19 patients.

Due to public pressure and clamor, DepEd moves school opening to October 5

“We have proven today that the people’s voices can and will triumph, and we shall continue to push the government to fulfill the requisites for a safe, accessible, and quality education,” ACT said in a statement.

The post Due to public pressure and clamor, DepEd moves school opening to October 5 appeared first on Kodao Productions.

Motorcycle backriding allowed, face shields a must for commuters in Davao

The Davao City government has made two adjustments in its quarantine protocols for commuters: back riding on motorcycles will be allowed for all, and face shields must be worn inside public transport units.

His rule begins

“The tyrant dies and his rule ends, the martyr dies and his rule begins.”

– Soren Kierkegaard

By DEE AYROSO

The post His rule begins appeared first on Bulatlat.

Road to Europe: Paved with exploitation of Filipino truck drivers

By Ana P. Santos

MANILA, Philippines

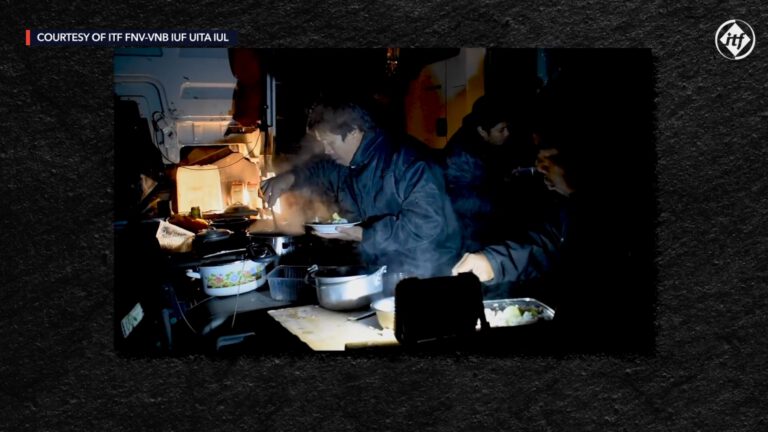

Drivers sleep, eat and live in their trucks or lorries – a space not bigger than 4 square meters – relieving themselves in their trucks or on the roadside

Jojo jumped at the opportunity to work in Europe. He never thought he would end up as a cautionary tale, living in a safehouse in Poland with 7 other Filipino drivers who are all victims of human trafficking.

In 2018, he first worked for a trucking company that promised him €1,100 ($1,235 or P68,897). Then another company in Poland offered him and his colleagues €1,800 ($2,021 or P100,372) plus accommodations.

Both companies did not pay their promised salary. Instead, Jojo drove around Europe for months at a time not knowing when he would get paid. Without money to book accommodations during cross country trips, he lived in his truck, making it his sleeping and eating quarters.

In a video interview conducted by The Federation of Dutch Trade Unions (FNV-VNB), Jojo played back an audio recording revealing how his employer threatened him when he asked for his salary. “Why are you not driving? You motherfucker. Where can you work in the Philippines for €100? And you come here and to me you are making yourself a hero. I’ll come there. I’ll fuck your mother.”

The company paid only a fraction of the €1,800 ($2,021 or P100,372) salary they committed to pay Jojo and the other truck drivers. The case remains under investigation by European authorities that’s why the company cannot yet be named.

Things did not get better when Jojo found a new employer in Romania with operations in the Netherlands.

His employer provided him with shelter but not a salary. Jojo begged, pleaded, and reasoned with his employer but he was only given a €50 ($56.27 or P2,789) food allowance.

Jojo and his companions have been given official status as victims of human trafficking and are under the protection of the local authorities.

The video is part of a joint report that a group of international federation of trade unions released in June, highlighting how the European transport industry has long been built on the exploitation of foreign drivers contracted from the Philippines and other low-wage European countries like Ukraine, Uzbekistan, and Romania.

Migrant truck drivers are paid wages as low as €1.76-€2.13 ($1.97-$2.39) per hour while they transport goods manufactured by multi-million dollar corporations throughout the wealthiest European countries like Germany, France, and the Netherlands.

A report series by Investigate Europe showed that the most to benefit from these “sweatshops on wheels” are car companies like Renault, BMW, Volkswagen, and Jaguar that hire the haulage companies.

Some of the truck drivers receive a fixed monthly salary of €100 to €600 ($112 to $674) plus a per diem to cover food and accommodations while on the road but this is not sufficient to cover the cost of decent sleeping quarters in expensive European countries.

In comparison, their EU-national counterparts are paid anywhere between €1,500 ($1,688 or P83,821) to €2,500 ($2,814 or P124,143) on top of a per diem for doing the same job.

The trade union report is based on interviews with driversand other industry sources from different European countries conducted during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as various documents and research data. The FNV-VNB, along with the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) and the International Union of Food and Allied Workers’s Associations (IUF) compiled the findings of the report.

About 75% of the inland freight that moves through the 27 countries that comprise the European Union (EU) are transported by cargo trucks. The transport of goods across the massive land area that is the continent of Europe is crucial in the supply chain – especially during a global pandemic like COVID-19 when airports are closed and flights are restricted as part of lockdown measures meant to curb the spread of the virus.

Transport trade unions estimate that there are about 150,000 non-EU truck drivers in Europe who are “working and living in appalling conditions.”

Truckers or “big rig” drivers are literally on the road – continuously driving for months at a time with limited rest days and no medical insurance. Drivers sleep, eat and live in their trucks or lorries – a space not bigger than 4 square meters – relieving themselves in their trucks or on the roadside.

During the brutal European winter months when employers would refuse to repair heating systems, drivers would resort to using the camping gas stove that they use to cook as a source of heat. It is dangerous but drivers said the other option is to freeze out in the cold.

Pandemic as excuse to cut wages

Among the report’s findings is that transport companies are now capitalizing on the COVID-19 pandemic to further cut or withhold wages even while pressuring drivers to make speedy deliveries of essential goods like food and medical equipment.

Drivers are not provided with proper protective gear, thus increasing their risk of contracting the virus. Drivers are left with no choice but to buy protective gear themselves, taking it out of their already low wages.

Cited in the report was a memo issued by a multinational company which used falling demand and a drop in fuel prices as a consequence of the pandemic to justify a “request to reduce your transport prices.”

This reduction is often taken out of the salaries of drivers who say that even with less demand, they are working more than ever as other modes of transport in the supply chain were disrupted by border closures and movement restrictions.

“During COVID-19 me and my colleagues are doing transports [sic] in Western Europe. But our employer tells us that he cannot pay our salaries because his invoices are not being paid by the operator we work for,” said a Filipino driver interviewed in the report. He had not received his salary since January 2020.

Marlon Toledo Lacsamana, secretary general of Migrante Netherlands-Den Haag, said that these exploitative labor practices were exacerbated by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Philippine embassies and consulates were closed or operating with a [skeleton] workforce. When borders within Europe closed, truck drivers were cut off from the embassy, Filipino organizations, and local unions which could act as a check and balance and offer assistance,” said Lacsamana in a text message.

Hans Cacdac, administrator of the Overseas Workers Welfare Association (OWWA), acknowledged the long-standing exploitation of Filipino truck drivers in Europe. “This is a problem that we would normally solve through rescue, assistance, and repatriation. This is now made more complicated by the health aspects of COVID-19.”

Third country hiring

A shortage of truck drivers across Europe, decades of deregulation and widespread subcontracting, along with a loophole in labor laws, have allowed trucking companies based in Eastern Europe to hire migrant and non-EU drivers and pay them much lower wages than the standard in the countries that the drivers are made to work in.

“These drivers are contracted by companies based in Eastern European countries that they will never work in. They almost exclusively drive around Western Europe where wages are higher,” said Edwin Atema, a lead investigator from FNV-VNB who spoke to Rappler via phone from the Netherlands.

“Transport companies treat foreign truck drivers like car keys that can just be left anywhere without a salary, water, or food. Like they can be turned off or on whenever the employers want.”

According to Cheryl Daytec, the labor attaché at the Phiippine Overseas Labor & Office (POLO) in Geneva, Switzerland, trucking companies get away with paying low wages through “third country hiring,” a method of hiring Filipinos through another country like Qatar, Malaysia, Singapore, United Arab Emirates, or Taiwan (and not directly from the Philippines). From here, Daytec told Rappler in a phone interview, they apply for a working visa in a Polish consulate to facilitate their entry to Europe.

Before a Polish consulate opened in Manila earlier in 2020, the drivers would fly to Malaysia where visas are not required of Filipinos, and from there, apply for a Polish working visa to enter Europe.

“In reality, the drivers are only in Poland once every 3 months,” said Daytec, who oversees Philippine migrant worker issues in Poland and the Czech Republic.

This route circumvents the Philippine Overseas Employment Agency (POEA) hiring process that has safeguards against underpaying of wages and violation of worker rights. It also prevents the Philippine government from knowing how many Filipinos have been trafficked into European countries.

“We usually only learn about their situation when we are alerted to a migrant worker in distress,” said Daytec.

When COVID-19 hit and many overseas Filipino workers lost their jobs, the government rolled out the AKAP social assistance programme offering financial assistance of $200 for displaced workers.

“The Philippines is one of the few countries providing this kind of assistance to their workers in a foreign country. Ideally, it is the hiring country that should be taking care of foreign workers they hired and are now displaced by the pandemic,” Daytec added.

The POLO in Geneva has negotiated a contract with an eastern European trucking company that standardizes truck driver wages at €1,500 ($1,688) and is compliant with European guidelines in limiting driving hours and observing rest times.

The provisions in the contract are being reviewed by the POEA as a standard model contract that may be adapted by trucking companies in Eastern Europe.

“It’s definitely a big improvement from the usual $450 (P22,355) wages that were previously promised to our truck drivers,” said Daytec. (To be concluded) – Rappler.com

Originally posted on Rappler. Click this link for the original post: https://rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/road-to-europe-paved-with-exploitation-filipino-truck-drivers

Para Po Sa Inyo! Art Exhibit: TUP artists raise funds for jeepney drivers through artworks

Technological University of the Philippines (TUP) Manila artists and “Para Po Sa Inyo! Art Exhibit” are selling their artworks to raise money for the displaced jeepney drivers in Metro Manila. Artworks of local artists from TUP artists from P1,000 pesos are up for grabs, with 60% percent of the proceeds going to the fundraiser. “Para […]

The post Para Po Sa Inyo! Art Exhibit: TUP artists raise funds for jeepney drivers through artworks appeared first on Manila Today.

Karapatan on Kian Loyd Delos Santos’ 3rd death anniversary: justice remains elusive for drug war victims

On the third anniversary of the murder of 17-year-old Kian Loyd Delos Santos, human rights watchdog Karapatan reiterated its call for justice, which the group asserted, “remains elusive for the thousands of victims killed in the government’s sham and bloody war on drugs as it continues to claim more and more lives with rampant impunity.”

Breakdowns

As the number of the infected swells and threatens to overwhelm the healthcare system, the country’s medical frontliners have wisely called for the reassessment and reform of what passes for the Duterte regime’s anti-COVID-19 strategy. But they did not include in their proposals the need to address the possibility that we may also be in the middle of a mental health crisis that will quite possibly have a long-term impact on Philippine society. The physical and mental well-being of its people is after all among a nation’s chief assets, since only mentally healthy citizens can function as productive and responsible members of the community.

As entire economic systems break down, and recessions and even a repeat of the Great Depression of the 1930s become more and more likely, not only unemployment and want have distressed millions in the heels of the COVID-19 crisis. Since it declared the contagion a global pandemic last March, the World Health Organization (WHO) has been warning the countries afflicted and the world at large that among its consequences will be a spike in mental health problems. The problems referred to include anxiety disorders, panic attacks, psychoses, clinical depression and even suicidal tendencies.

In its report last May on the extent of the COVID-19 problem and its prognosis for the future, the WHO not only warned that the disease “may not go away,” its Mental Health Department also noted during its virtual conference with health ministers in Geneva, Switzerland that COVID-19 is leading to a global mental health crisis that “has to be addressed urgently.”

The Department Director said that “the isolation, the fear, the uncertainty, the economic turmoil” that are among the consequences of the global pandemic “all cause psychological stress.” As a result, the world should expect an increase in mental illness, especially among children, young people and health workers.

The unique characteristics of the disease, and hence the steps being taken to combat it, make it particularly conducive to mental distress. The quarantine protocols needed to control it, among them working, teaching and learning from home, limiting physical mobility and avoiding crowds, have made the isolation that leads to loneliness, fear, despair and hopelessness the primary condition of existence for millions of people all over the planet. Because COVID-19 can be transmitted primarily through human-to-human contact, even if a vaccine were found, the fundamental preventive means of avoiding the company of others — at times including not only friends, neighbors, co-workers and associates, but even members of one’s immediate family — will continue to be among the preferred approaches to controlling the contagion, as contrary to the basic human need for companionship and social interaction as it may be.

In recognition of the long-term impact of the pandemic on the mental health of the world’s populations, the United Nations has urged governments to improve their capacity “to minimize the mental health consequences of the pandemic” by 1.) “adopting a-whole-of-society approach to promote, protect and care for mental health”; 2.) ensuring “the widespread availability of emergency mental health and psychosocial support”; and, 3.) enhancing citizens’ recovery from COVID-19 by building mental health services for the future.”

The first requires, among others, including mental health concerns in whatever “national response plan” a government may have, and reducing the number of incidents that harm mental well-being such as the “acute impoverishment” of its constituents.

The second includes strengthening social cohesion by helping those isolated at home to stay connected with others, and protecting the human rights of those with mental health issues by making sure they have access to appropriate care.

The third demands raising the capacity of governments to deal with mental health problems by investing in the reform of universal healthcare networks, which among others means including mental health among their priority concerns.

These are only a few of the recommended programs of action the UN recommends; there are several others. But even the implementation of these few is in the Philippines already problematic.

The punitive, arrest-and-jail-them-all orientation of the Duterte regime in dealing with the pandemic not only contributes to the spread of the disease by packing alleged violators of quarantine protocols into the country’s notoriously overcrowded prisons. It even adds to the fear and anxiety of much of the population.

There is also the already “acute impoverishment” of millions of disemployed Filipinos that the regime is unable to remedy due to the many “difficulties” — among them the corruption, inefficiency and sheer incompetence of many of its own officials — it has admitted it has had to cope with in controlling the economic impact of the pandemic on the citizenry.

Filipino psychiatrists have not been remiss in alerting the public and the government to the looming if not already existing mental health problem and have reported a notable increase in the number of consultations during the pandemic. But neither the citizenry nor the Duterte regime seems to regard it with any sense of urgency. Their indifference is consistent with mental health’s being least prioritized in Philippine governance and society. Part of the reason is the persistence of the thinking that those with mental health issues are somehow at fault and are to be shunned, despised, and even publicly humiliated and ridiculed.

And yet the problem is more common than mass and official prejudice seems to assume, and, as the WHO has cautioned, is thus likely to worsen. Even before the pandemic, according to the Department of Health, 5.3% of the Philippines’ 100 million plus population, or more than five million people, were already suffering from various forms of depressive disorders. Some 16% of students in their teens, a WHO study found in 2011, have contemplated suicide, while still others have actually attempted it once or even several times.

Such anecdotal evidence as the incidents of random, meaningless violence, and of individuals’ clambering up billboards and high-rise buildings and threatening to jump from them; the half-naked human derelicts one often sees roaming the streets mumbling to unseen beings; the suicides among the young that have become so common they merit only a casual mention in much of the media; and the fact that many Filipinos have a weird relative or two somewhere whom the family never mentions, support these findings. But the even worse news is that there are only a few thousand clinical psychiatrists in the Philippines, and mental health institutions few, inadequately staffed and funded, and absent in many areas.

It seems only reasonable to expect that in addition to devising effective means to halt or at least reduce the transmission of COVID-19, mitigating the economic impact of the pandemic and recovering from the economic recession, the government should also seriously look into reducing the mental health costs of the current public health emergency.

It can start with implementing what is doable among the steps the United Nations has suggested governments should take. It will admittedly take some doing in this country. But any government aware of its responsibility to protect its citizens and prevent the breakdown of Philippine society should be able to understand that it has no choice but to address the problem before it, too, becomes as widespread and as unmanageable as the social injustice, the mass poverty, the corruption in high places, the oppression and the inequality that, like the threat of COVID-19, haunt this country and its people.

Luis V. Teodoro is on Facebook and Twitter (@luisteodoro).

www.luisteodoro.com

Published in Business World

August 13, 2020

The post Breakdowns appeared first on Bulatlat.