Philippine Daily Inquirer / 04:08 AM August 24, 2020

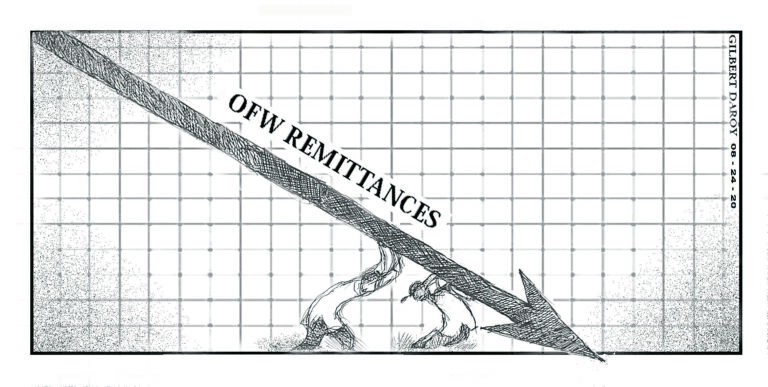

How bad has been the downturn in the remittances of overseas Filipino workers (OFWs), long a lifeline of the Philippine economy but which have been battered by the worldwide pandemic as tens of thousands of OFWs have lost their jobs and are streaming home?

For three straight months starting last March, OFW remittances contracted. In March, the inflows declined by 5.2 percent year-on-year to $2.65 billion. The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) attributed this chiefly to labor cutbacks in the oil industry of the Middle East following the collapse in crude prices.

In April, remittances fell sharply by 16.1 percent to $2.28 billion, which the BSP blamed on the layoff of OFWs in countries heavily affected by the pandemic and the temporary closure during the lockdown of some banks that provide money transfer services. In May, the decline worsened to 19.2 percent to $2.34 billion, as global economic activity, especially travel and employment, reeled from the pandemic, resulting in massive job losses or the deferred hiring of many OFWs.

An uptick was recorded in June, but the increase in the amount of dollars sent home that month by Filipinos abroad is by no means an indication that the lot of migrant workers—and our consumer-driven economy for that matter—has turned the corner. The global economic recession is expected to linger as countries struggle to contain the pandemic. Like the Philippines, many other nations both developing and advanced are suffering unprecedented economic declines. Japan, for instance, reported a 27.8-percent contraction in the second quarter. The US economy shrank by a bigger 32.9 percent.

Household consumption accounts for two-thirds of the Philippine economy. This consumption, in turn, is partly driven by the dollars sent home by the more than 10 million Filipinos working abroad. Last year, they remitted $33.5 billion (about P168 billion at current exchange rates) to their families here, or the equivalent of 9.3 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). These remittances have for decades fueled domestic consumption and cushioned the economy against external shocks. It is estimated that about 12 percent of Philippine households depend on the remittances that OFWs send.

However, such cash inflows have now considerably slowed down with the COVID-19-induced recession. Data from the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) showed that the number of OFWs seeking assistance due to the effects of the pandemic had surged to more than 600,000 as of Aug. 15, of which less than half or 272,000 had been approved.

Of those seeking assistance, 349,977 are workers displaced and stranded overseas, while 254,426 are repatriated land- and sea-based OFWs. The DOLE provides a one-time $200 or P10,000 assistance to migrant workers affected by the pandemic. As of Aug. 15, more than half (146,658) of the OFWs who arrived in Manila have been transported back to their home provinces.

It is now a given that in 2020, remittances will shrink for the first time since 2001, when inflows from OFWs were down by 0.3 percent. The government expects remittances this year to contract by about 20 percent. That’s $7 billion less inflows into the pockets of millions of Filipino families, many of whom are struggling as the country internally staggers from the impact of the pandemic.

For years, the availability of cash from such remittances allowed the Filipino populace to spend readily and fuel the boom in the country’s consumer-driven economy. But the flush times are over, at least for now. OFWs are forecast to be particularly hit hard as COVID-19 shutdowns worldwide continue to affect sectors employing migrants, in particular restaurants and tourism services, and retail and wholesale trade.

As it is, while these modern-day heroes have lost their jobs, many continue to suffer upon returning home because the government can’t seem to cope with the extent of the crisis. No comprehensive plan is in place to address the plight of displaced OFWs. With thousands of them still stranded in Metro Manila and even abroad, the administration needs to tap, as an immediate measure, the private sector in carrying out the testing and quarantine of returning OFWs in the capital, ferrying them to their home provinces, and finding livelihood for them and their families. Part of the government’s stimulus package must also go to helping these displaced OFWs.

What has become clear at this point is that OFW remittances, on which the Philippine economy has depended for far too long, are also not insulated from economic crises. The long-term challenge for this administration, and succeeding ones, is how to make the economy less vulnerable to such disruptions by weaning the country away from its long-staying labor-export policy that has spawned the Filipino diaspora, and building a truly self-sufficient national economy with jobs for all.