From opportunistic generals to kangaroo courts, some things don’t seem to change.

By Justin Umali | May 15, 2019, www.esquiremag.ph

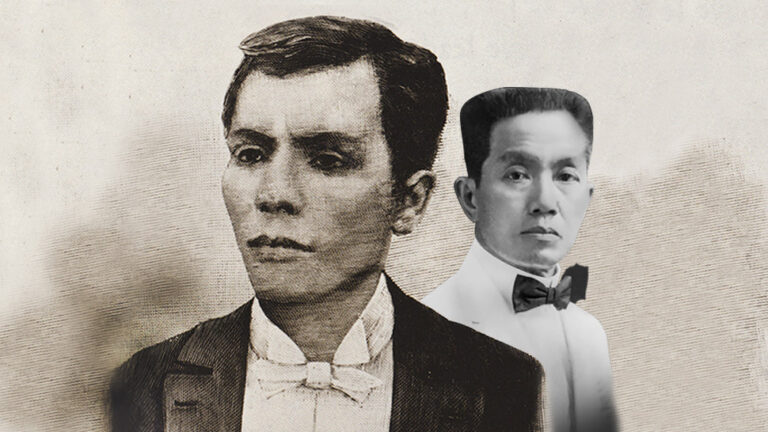

One hundred twenty-two years ago, one of the most pivotal events in Philippine history occurred: Two brothers, Andres and Procopio, were killed in the mountains of Marogondon. The execution of the Bonifacio brothers on Emilio Aguinaldo’s orders signified a new change in the Philippine Revolution, one that would ultimately lead to the Pact of Biak-na-Bato and Aguinaldo’s exile to Hong Kong.

Multiple anecdotes have been written about the incident, and the story of Bonifacio’s trial and execution are well-known, but some details still remain unclear even now. Here, a look back at the events leading to that fateful day.

Two Boys Falling Out

Why did Aguinaldo send Bonifacio to his death? The conflict ultimately started after the events of the Tejeros Convention. Bonifacio, who felt that the Magdalo faction maneuvered to rig the elections (tenuous at best; most of the Cabinet was from Bonifacio’s Magdiwang), stormed out and declared the results of the convention null and void, drawing up the Acta de Tejeros with 44 other generals signing the document. Meanwhile, Aguinaldo was surprised he was even elected President. He was busy in Silang when word came that he won an election.

The moments after Tejeros were tense for both parties. Bonifacio made his way to Naic with 40 other generals, including some of Aguinaldo’s men, to further denounce the results of Tejeros, creating the Naic Military Agreement. They declared that all military forces be consolidated under Pio del Pilar or face treason.

When Aguinaldo heard of this, he made his way to Naic to see what was going on himself. Though suffering from malaria at the time, he managed to reach the town and confronted Bonifacio, who was meeting with Aguinaldo’s generals Artemio Ricarte, Mariano Noriel, and del Pilar. The two were surprisingly civil: Bonifacio invited him, saying, “Magtuloy po kayo at makinig sa aming pulong.” Aguinaldo replied, “Salamat po, at marahil kung ako’y inyong kailangan, disin sana’y inanyayahan ninyo ako,” before leaving.

The Arrest at Indang

Aguinaldo took his time before deciding to act, taking care not to alienate Bonifacio’s supporters. Noriel and del Pilar immediately went back to Aguinaldo’s side, as did others. Bonifacio decided to camp near Indang with around 1,000 men, corresponding with Emilio Jacinto and Julio Nakpil up north and drawing up plans for an offensive in Laguna. This would prove to be fatal, however, as Bonifacio’s courier, Antonino Guevara, failed to deliver the messages and instead spent the time around Indang. The Supremo was left waiting for replies that never came.

Meanwhile, reports from Severino de las Alas and Jose Coronel reached Aguinaldo. By this time, Aguinaldo had finished consolidating his power base among the Cavite elite, giving him the confidence to act. Armed with allegations of Bonifacio burning down a village and ordering the burning of a church in Indang, he decided to exercise his prerogative as President and arrest Bonifacio, dispatching Agapito Bonzon and Jose Ignacio Paua to arrest the Supremo.

What happened next would live in infamy. Bonifacio received the party cordially, but were met with attack. Bonifacio ordered his men to stand down, refusing to fight his “fellow Tagalogs,” cries that were made in vain. A few shots were fired, and Bonifacio was shot in the arm by Bonzon and stabbed in the neck by Paua. Bonifacio’s brother, Ciriaco, was shot dead. His other brother, Procopio, was beaten. His wife, Gregoria de Jesus, was raped by Bonzon. Bonifacio, starved and wounded, was carried in a hammock to Naic, where Aguinaldo waited.

The Arrest at Indang

Aguinaldo took his time before deciding to act, taking care not to alienate Bonifacio’s supporters. Noriel and del Pilar immediately went back to Aguinaldo’s side, as did others. Bonifacio decided to camp near Indang with around 1,000 men, corresponding with Emilio Jacinto and Julio Nakpil up north and drawing up plans for an offensive in Laguna. This would prove to be fatal, however, as Bonifacio’s courier, Antonino Guevara, failed to deliver the messages and instead spent the time around Indang. The Supremo was left waiting for replies that never came.

Meanwhile, reports from Severino de las Alas and Jose Coronel reached Aguinaldo. By this time, Aguinaldo had finished consolidating his power base among the Cavite elite, giving him the confidence to act. Armed with allegations of Bonifacio burning down a village and ordering the burning of a church in Indang, he decided to exercise his prerogative as President and arrest Bonifacio, dispatching Agapito Bonzon and Jose Ignacio Paua to arrest the Supremo.

What happened next would live in infamy. Bonifacio received the party cordially, but were met with attack. Bonifacio ordered his men to stand down, refusing to fight his “fellow Tagalogs,” cries that were made in vain. A few shots were fired, and Bonifacio was shot in the arm by Bonzon and stabbed in the neck by Paua. Bonifacio’s brother, Ciriaco, was shot dead. His other brother, Procopio, was beaten. His wife, Gregoria de Jesus, was raped by Bonzon. Bonifacio, starved and wounded, was carried in a hammock to Naic, where Aguinaldo waited.

Ghosts of the Revolution

Bonifacio’s death marked a clear shift in the Katipunan and the Philippine Revolution in general. Bonifacio, Supremo, the Great Proletarian, was born of the masses and connected with the Katipunan’s nationalist and anti-colonial struggle.

In stark contrast, Aguinaldo and his men were part of the liberal educated ilustrado bourgeoisie. Aguinaldo himself was part of the Cavite elite and grew up surrounded by the trappings of privilege and upper middle class comfort. Bonifacio, on the other hand, grew up having to work to survive when his parents passed away.

The change in leadership transformed the aims of the revolutionary movement and essentially doomed it to failure. At its core, the revolutionary movement was an anti-colonial and anti-feudal struggle led by the masses through its leader, the Supremo Andres Bonifacio. When Aguinaldo and his faction took over the struggle, it lost its anti-feudal character—why would Aguinaldo wish to remove the very system he benefited from?

This disconnect between the leadership’s aims and that of the people was what ensured that the Katipunan would not succeed. Ultimately, Aguinaldo led the revolution to exile, then to American colonialization; both far removed from Bonifacio’s ideal.

And yet, Bonifacio lives on in the struggle for true independence. A hundred years on, some things didn’t change. The nation is still dominated by foreign interest, semi-feudal relationships, and systemic profiteering at the expense of the Filipino people. Andres Bonifacio may have perished in the mountains of Marogondon, but his spirit still inspires and leads the Filipino people in their search for freedom.

Ghosts of the Revolution

Bonifacio’s death marked a clear shift in the Katipunan and the Philippine Revolution in general. Bonifacio, Supremo, the Great Proletarian, was born of the masses and connected with the Katipunan’s nationalist and anti-colonial struggle.

In stark contrast, Aguinaldo and his men were part of the liberal educated ilustrado bourgeoisie. Aguinaldo himself was part of the Cavite elite and grew up surrounded by the trappings of privilege and upper middle class comfort. Bonifacio, on the other hand, grew up having to work to survive when his parents passed away.

The change in leadership transformed the aims of the revolutionary movement and essentially doomed it to failure. At its core, the revolutionary movement was an anti-colonial and anti-feudal struggle led by the masses through its leader, the Supremo Andres Bonifacio. When Aguinaldo and his faction took over the struggle, it lost its anti-feudal character—why would Aguinaldo wish to remove the very system he benefited from?

This disconnect between the leadership’s aims and that of the people was what ensured that the Katipunan would not succeed. Ultimately, Aguinaldo led the revolution to exile, then to American colonialization; both far removed from Bonifacio’s ideal.

And yet, Bonifacio lives on in the struggle for true independence. A hundred years on, some things didn’t change. The nation is still dominated by foreign interest, semi-feudal relationships, and systemic profiteering at the expense of the Filipino people. Andres Bonifacio may have perished in the mountains of Marogondon, but his spirit still inspires and leads the Filipino people in their search for freedom.