Ratziel San Juan (Philstar.com) – November 13, 2019

MANILA, Philippines — Progressive artist group Panday Sining has been under fire for painting protest slogans such as “Presyo, Ibaba! Sahod, Itaas!” and “US-China Layas!” at the Lagusnilad underpass in Manila.

The city’s Department of Engineering and Public Works has since led the repainting of the affected portions of the underpass near the city hall, but Mayor Isko Moreno’s message remains: “Kapag nahuli ko kayo, ipadidila ko sa inyo ito.” (If I catch you, I will make you wipe that off with your tongue.)

“Ang ganda ganda na eh. Ang linis na. (It’s already beautiful. It’s now clean.) It took 15 years for that underpass to be attended. Nobody attended to that underpass,” Moreno, who led clearing operations in the underpass in July, said.

“Kayo ang nambababoy eh. Hindi makatwiran ‘yan. (You’re the one who made a mess. That’s not reasonable.) We don’t deserve this. The people of Manila don’t deserve this.”

The Manila City government reminded the public through social media that its anti-vandalism ordinance—Ordinance No. 7971—prohibits any person from defacing public and private property.

Panday Sining, however, maintained that its reasons for tagging the underpass are valid.

“To the public: sorry for the inconvenience, but the matter and issues at hand are urgent. Left and right, ordinary people are being killed or jailed for criticizing this corrupt and fascist government,” Panday Sining said in a Tuesday post.

“The space for peaceful and democratic speech is already being compromised by the regime…That is why Panday Sining, a cultural organization of the youth, conducted its Graffiesta as a response to these worsening economic and political state of the nation.”

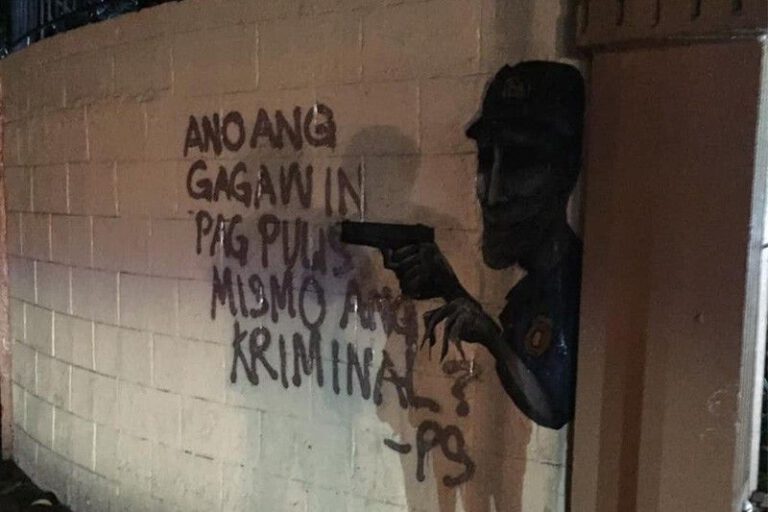

Panday Sining asserted that what the government calls vandalism, it sees as protest art.

What is protest art, anyway?

The late art critic and UP professor Alice Guillermo wrote that protest art—also termed revolutionary or progressive art—breaks down the academic and elitist notions associated with traditional forms that rely on inaccessible media like oil on canvas.

Protest art may take the form of posters, illustrations, comic books, graffiti, street murals, and other popular media less likely to alienate the audience. The important thing is that they are “infused with meaningful political content.”

Simple to make while still applying universal standards of aesthetics, protest art is designed to have a broad appeal fit to deliver the most important part of the piece: its message.

“Instead of the ideal of the masterpiece, revolutionary art is responsive to issues and creates attitudes with respect to daily events. Therefore, its value lies in its flexibility, its sensitivity to issues, and its quickness to respond,” Guillermo wrote in 1993.

“Likewise, instead of the ideal of permanence, much of art done in the midst of struggle, because of the necessity for quick campaigns along with the risks involved, is transitory, like graffiti and instant street murals, but always fresh, renewable, and inexhaustible.”

In the local setting, creating progressive art means understanding the cultural situation of the Philippines and its people. It also entails learning from and directly addressing different classes and sectors like farmers and workers.

Contemporary art scientist Alain Colombini wrote that while graffiti exists across many societies with different cultural contexts, a common motivation exists.

“Modes of expression are mainly related to visibility, notoriety, choice of venue, transgression, and are often a mean to react and protest while remaining anonymous, by illegally introducing messages in the public space,” Colombini wrote in 2018.

The resulting debate is if graffiti (text-based) and street art (image-based) constitute as art or a mere act of vandalism.

Why do people resort to protest art?

Donna Miranda of SAKA (Sama-samang Artista para sa Kilusang Agraryo), a group of artists and peasant advocates, told Philstar.com that even under the legal framework, there is no nationwide law that prohibits vandalism.

Miranda said that while ordinances penalize graffiti and street art in cities like Manila, it can be argued that national and constitutionally-guaranteed rights should have more weight.

“Napakahalagang mensahe no’n (Panday Sining graffiti) para sa masang Pilipino. Sinasabi no’n protektahan ang ating soberanya. At binura ‘yun ng LGU ng Manila.”

(The Panday Sining graffiti has an important message for the Filipino people. It says that we should defend our sovereignty. And the Manila local government unity erased that.)

“May malaking sinasabi ‘yun sa panunupil ng ating karapatan, hindi lang magpahayag pero ng ating assertion ng ating karapatan for self-determination and sovereignty.”

(That says a lot about how our rights are repressed, not just to freedom of expression but also our assertion of our right to self-determination and sovereignty.)

‘Street art accepted abroad’

Miranda also said that street art itself is not controversial and has already been accepted in the field of art as a legitimate form, citing murals, commissioned and otherwise, that have become popular locally and abroad.

“‘Yung street art makikita na natin siya in a way halos tinanggap na siya nung art institution, lalong lalo na yung mga sikat na artists katulad nina Banksy…[at sa] BGC, maging sa ibang lugar kunwari Singapore at sa Melbourne — halos tourist areas yung mga lugar na punong puno ng street art.”

(Street art is virtually accepted by the art institution, especially with famous artists like Banksy…and in places like Bonifacio Global City, Singapore, and Melbourne — street-art filled locations have practically become tourist areas.)

Street and protest art are featured in documentaries like “Exit Through the Gift Shop” (2010) and books such as “Trespass: A History Of Uncommissioned Urban Art” (2010).

The message and not the form of protest art, Miranda says, is what polarizes, since these usually depict underreported issues only heard of in activist circles.

“[S]omehow, ‘pag yung graffiti ay nagpapahayag ng mga panawagan tulad ng ‘itaas ang sahod’ o protektahan ang soberanya ng isang bansa, hindi na ito katanggap tanggap.”

(Somehow, if the graffiti calls for rights like ‘raise wages’ or to protect the sovereignty of a nation, it becomes unacceptable.)

“Yung mismong cities pag ang nagko-commision, pero pag nagapanawagan ka ng tunay na reporma sa lupa…bakit sinusupil ‘yun?”

(Cities themselves commission street art, but when the works call for genuine agrarian reform, why is it censored?)

Vandalism in plain sight

Iconic street artist Banksy himself has weighed in on negative sentiments against street art and the not-so-controversial presence of advertising in our lives.

“To some people breaking into property and painting it might seem a little inconsiderate, but in reality, the 30 square centimeters of your brain are trespassed upon every day by teams of marketing experts,” iconic street artist Banksy said.

“Graffiti is a perfectly proportionate response to being sold unattainable goals by a society obsessed with status and infamy. Graffiti is the sight of an unregulated free market getting the kind of art it deserves.” PA