By: Kurt Dela Peña – Content Researcher Writer/INQUIRER.net / October 27, 2021

MANILA, Philippines—Every year, typhoons leave the Philippines ravaged—crops, homes and lives severely wrecked.

It was in 2013 when Typhoon Yolanda, which carried winds of more than 300 kph, devastated the Visayas and left widespread damage worth P95 billion.

READ: One of world’s strongest typhoons lashes Philippines

Dr. Alvin Ang, in 2014, said in his Eagle Watch column that the economy of the Philippines had “significant resilience.”

With the COVID-19 crisis, however, typhoons lead to a long-lasting problem, the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) said.

In 2020, the Philippines was hit by 22 typhoons, including Typhoons Rolly, Quinta and Ulysses. Rolly left damage worth P13.9 billion.

READ: Rolly is world’s strongest typhoon so far in 2020 — Pagasa

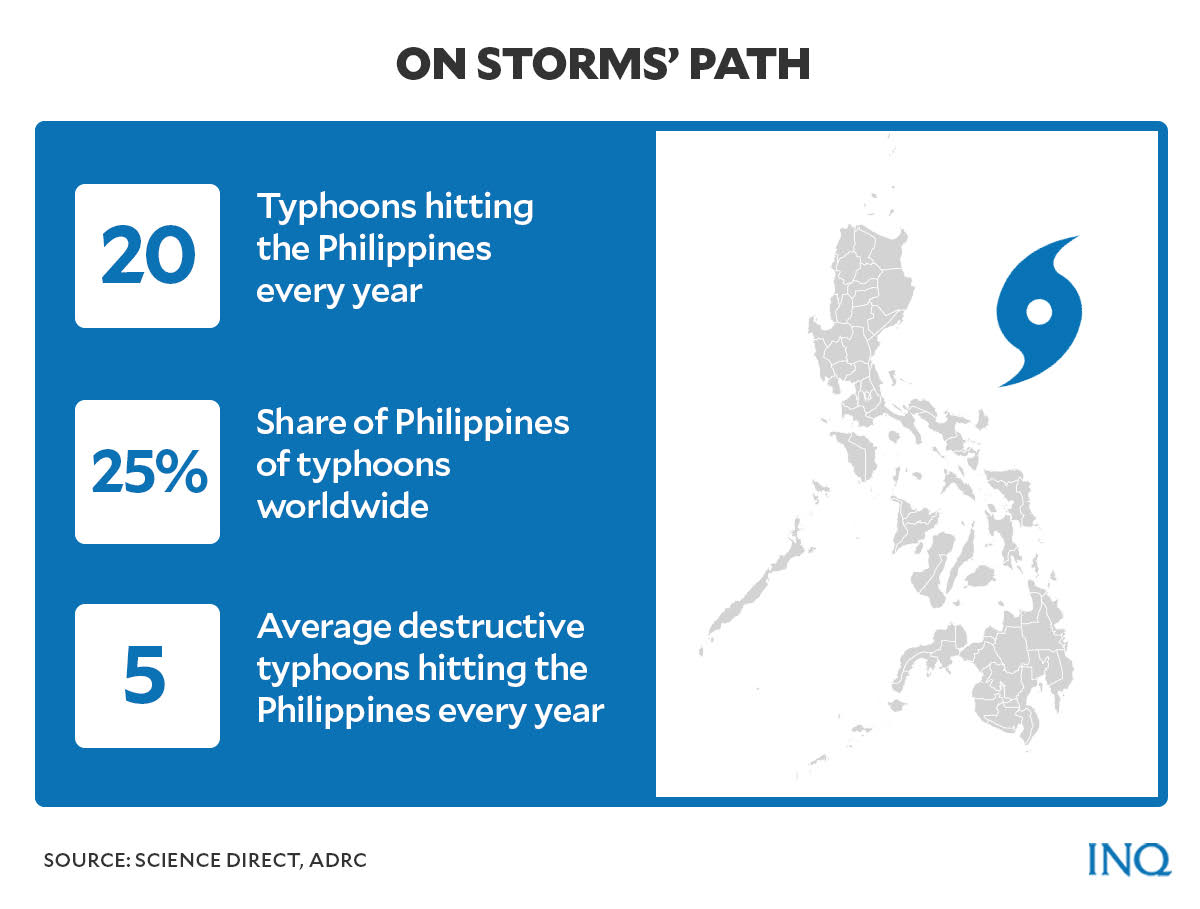

The website Science Direct said that every year, an average of 20 typhoons—25 percent of the total typhoons in the world—barrel their way into the Philippines.

Graphic by Ed Lustan

Out of the 20 typhoons, five are considered destructive while an average of nine typhoons make landfalls, the Asian Disaster Reduction Center said.

The NCBI said that typhoons in 2020 had a devastating impact on an “already poverty-stricken” nation, with the intensifying COVID-19 crisis.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) said “those burdened most from these impacts are the poor, the marginalized, and the isolated.”

READ: PH urged to face risks from calamities head on

Lost resources

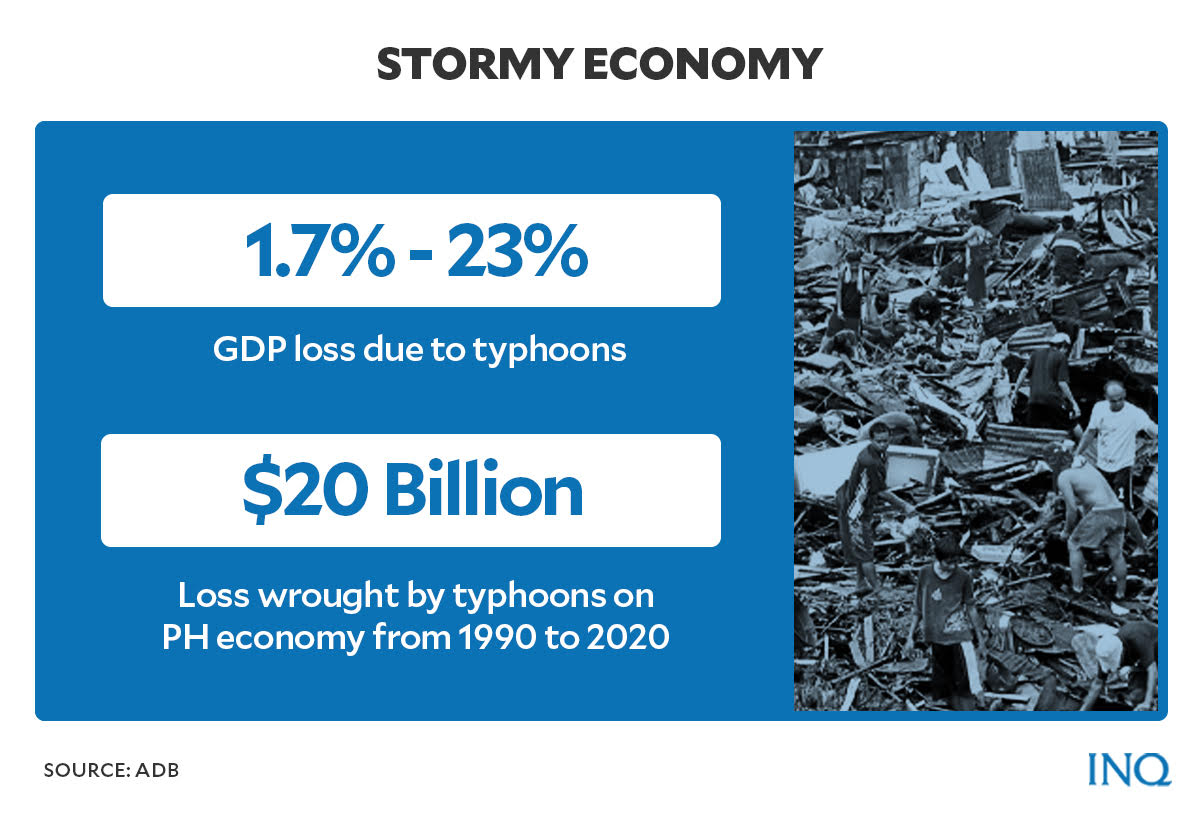

In its report “Disaster Resilience in Asia,” the ADB said that typhoons cost the Philippines some $20 billion in the last three decades (1990 to 2020).

These included the five strongest typhoons that hit the nation, as listed by the National Hurricane Center and the Joint Typhoon Warning Center:

Graphic by Ed Lustan

- Typhoon Rolly, 2020: Catanduanes (313 kph)

- Typhoon Yolanda, 2013: Leyte (305 kph)

- Typhoon Ferdie, 2016: Batanes (305 kph)

- Typhoon Juan, 2010: Luzon (289 kph)

- Typhoon Iliang, 1998: Luzon (289 kph)

It explained that typhoons in the Philippines can reduce economic activity by an average of 1.7 percent in the year they occur.

READ: Calamities slowed Philippine economy—official

“In the most severe cases, losses can be as high as 23 percent,” the ADB said, explaining that typhoons may cost a nation billions.

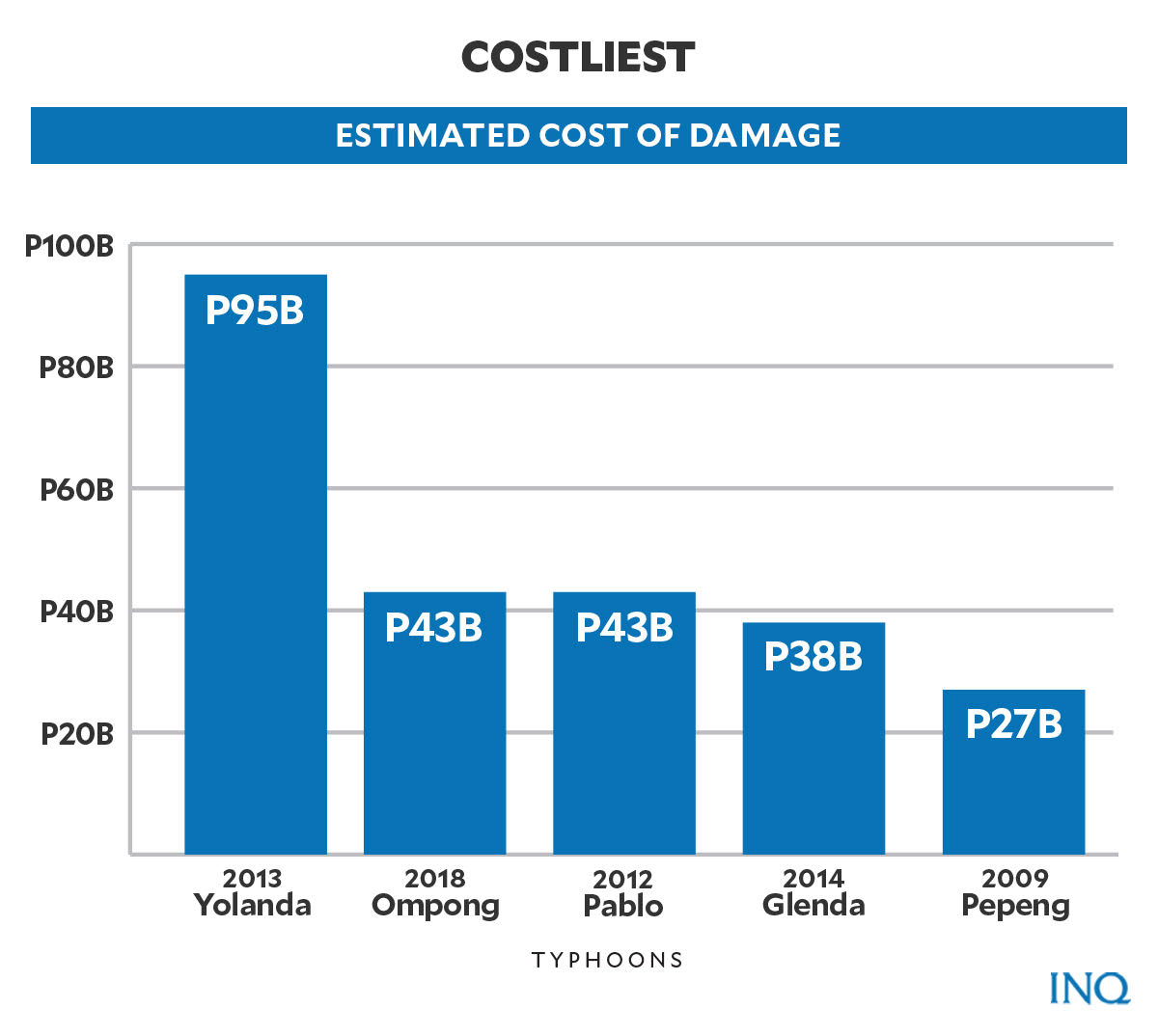

This was evident in how billions of pesos were lost because of typhoons that hit the Philippines with Yolanda leaving the biggest damage.

Graphic by Ed Lustan

- Typhoon Yolanda, 2013 (Visayas): P95 billion

- Typhoon Ompong, 2018 (Luzon): P43 billion

- Typhoon Pablo, 2012 (Mindanao): P43 billion

- Typhoon Glenda, 2014 (Luzon): P38 billion

- Typhoon Pepeng, 2009 (Luzon): P27 billion

Nightlight intensity

To identify how typhoons affect economic activity in the Philippines, the ADB employed nightlight imagery provided by the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program.

The ADB said nightlights provide data which can help identify “socioeconomic indicators” when no other reliable information exists.

“To this end, we used satellite-derived measures of nightlight intensity as measures of local economic activity,” the multilateral lender said.

It explained that it combined these with damages based on storm tracks, a wind field model and a stylized damage work.

The ADB found that typhoons with a return period of at least five years are likely to cause one percent “short-term” cut in economic activity.

In typhoons with a return period of at least 20 years, economic activity may be cut by at least two percent, saying that these “differ starkly” in regions.

Not resilience

The ADB said while the effects of typhoons in the Philippines were “often short-lived,” the continuation of the economy should not be viewed as resilience.

https://googleads.g.doubleclick.net/pagead/ads?client=ca-pub-3470805887229135&output=html&h=280&slotname=8007816029&adk=3301384702&adf=1434377183&pi=t.ma~as.8007816029&w=640&fwrn=4&fwrnh=100&lmt=1635360861&rafmt=1&psa=0&format=640×280&url=https%3A%2F%2Fnewsinfo.inquirer.net%2F1507342%2Ftyphoons-and-covid-how-much-more-can-ph-take&flash=0&fwr=0&rpe=1&resp_fmts=3&wgl=1&dt=1635341956210&bpp=23&bdt=4388&idt=811&shv=r20211020&mjsv=m202110200101&ptt=9&saldr=aa&abxe=1&cookie=ID%3D3a3ebda894ebf98f-223b722d02cb00f9%3AT%3D1635341823%3AS%3DALNI_MaFZcvDgG5JFlTSKtLolBrsCuWHBg&prev_fmts=0x0&nras=1&correlator=7353277365949&frm=20&pv=1&ga_vid=74678425.1635341819&ga_sid=1635341958&ga_hid=186415334&ga_fc=1&u_tz=120&u_his=4&u_h=768&u_w=1366&u_ah=728&u_aw=1366&u_cd=24&adx=185&ady=6291&biw=1349&bih=643&scr_x=0&scr_y=3775&eid=31062579%2C31062937%2C31062944%2C31063139%2C31062931&oid=2&pvsid=1461701132551212&pem=545&ref=https%3A%2F%2Fnewsinfo.inquirer.net%2F&eae=0&fc=896&brdim=-8%2C-8%2C-8%2C-8%2C1366%2C0%2C1382%2C744%2C1366%2C643&vis=1&rsz=o%7Co%7CoeEbr%7C&abl=NS&pfx=0&fu=128&bc=31&ifi=1&uci=a!1&btvi=1&fsb=1&xpc=YOOI20zdnO&p=https%3A//newsinfo.inquirer.net&dtd=28069

Graphic by Ed Lustan

It said that if nothing is done except the “restoration of activity,” bringing back people to their homes would mean placing them back in the path of danger.

In the coming years, climate change is expected to worsen the intensity and impact of disasters, especially in places considered “at-risk.”

READ: Pandemic-era disaster season

“For small countries, more extreme events mean more massive damage affecting wider swathes of the population,” it said.

“Without preventive action, the havoc wreaked from the most severe disasters remain not just life-threatening, but also poverty-inducing,” said ADB.