May 5, 2022, Lian Buan

Vloggers and social media influencers occupy a special place in the Marcos campaign, as Ferdinand Marcos Jr chooses to run away from tough questions

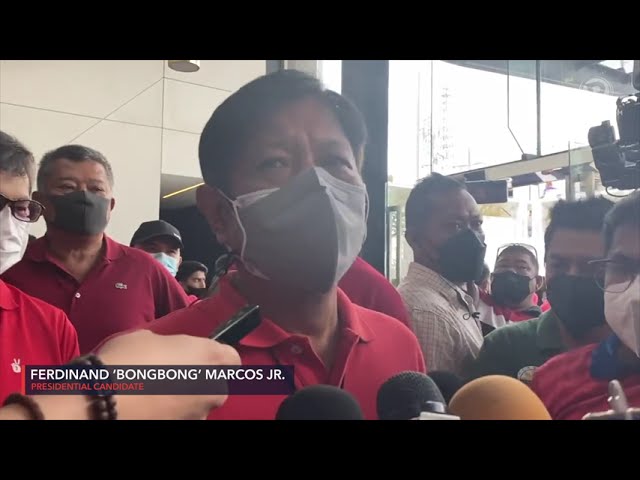

MANILA, Philippines – “Where are you taking me?,” a flustered Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. asked the security of the Marriott Hotel in Pasay City, frustrated that the long walk to his holding room has opened him up to an ambush interview by reporters wanting to ask him questions.

It was in that ambush interview on March 1 where he said there was no need to stand for Ukraine. His team had to take that back two days later in an emailed statement to media.

Marcos runs a presidential campaign that hides from and even blocks professional journalists who cover him – whether they belong to local or international newsrooms. His camp gives preferential treatment to vloggers, influencers, and the Sonshine Media Network International that is operated by the followers of doomsday preacher Apollo Quiboloy, who owns the company and is wanted in the United States for alleged sex trafficking of children.

“Marcos Jr. avoids real journalists because they are expected to raise the real issues and pose the tough questions. He’s allergic to them because they run counter to his disinformation narrative, which is at the heart of his election campaign,” said Christian Esguerra, a veteran journalist who also teaches journalism at the University of Santo Tomas.

“So, he naturally finds comfort in the company of ‘friendly’ journalists and social media influencers because he gets to control that narrative,” said Esguerra.

Evade at all cost

In a Zoom press conference on January 17, Marcos’ spokesperson Vic Rodriguez assured the press that his candidate will “always answer everything and anything.”

Marcos made the same promise after he filed his certificate of candidacy (COC) at the Commission on Elections (Comelec) on October 6, 2021, the last time he faced – at length – independent media that he did not pre-select.

“I have never refused any interview on any basis whatsoever,” Marcos said in response to a question after filing his COC. “I don’t know where that’s coming from, when have I refused to answer questions about anything?,” he asked, visibly miffed, and then declined to answer a follow-up question on his mother’s graft conviction, saying “not here and now.”

Only days after Rodriguez said his candidate was willing to answer anything, Marcos snubbed the first major presidential interview by GMA News where Marcos called the host, Peabody-award winning journalist Jessica Soho, biased and “anti-Marcos.”

This set the tone for what would become the Marcos campaign’s media policy: evade at all cost.

Marcos skipped all presidential debates, including those organized by Comelec, and declined Vice President Leni Robredo’s last-minute challenge to a one-on-one debate. He attended one-on-ones with news anchors and journalists that his campaign staff would vet for him.

Vloggers rule

In the Marcos campaign, vloggers are the priority.

At the Philippine Arena for the campaign kickoff on February 8, only select vloggers were allowed unfettered access to the area, while reporters and their crew were put in a boxed area.

“There was a security guard or two guarding the gate of the actual area. Some reporters were sitting on the floor. I noticed as Marcos whizzed past us, he was surrounded by a phalanx of red-shirted men like a presidential detail, and they were clearly surrounding him in a circle, and he was protected,” said Howard Johnson, BBC’s Philippine correspondent.

“Later that night, Sara Duterte said we must protect Bongbong, so there was a sense of him being protected from something, but at that early stage [I asked] from what? Being protected from media, to stop anyone from a doorstep (ambush) interview,” said Johnson.

From the start, the Marcos team chose reporters whom it notified about its accreditation process. Were it not for some of those reporters forwarding to their colleagues the accreditation instruction, many would not be issued the Uniteam IDs – the pass to covering any of their rallies.

Many Filipino reporters of foreign agencies were not accredited. “With a week to go before the elections, his media-relations team still has not granted accreditation to news staffers from over a dozen news agencies under FOCAP and does not regularly respond to inquiries about coverage, requests for comment and permissions for use of materials,” said the Foreign Correspondents Association of the Philippines (FOCAP) in a statement Tuesday, May 3, World Press Freedom Day.

Some international news teams who flew in later in the campaign period failed to get any access at all.

The Marcos team likewise hid the schedules of campaign sorties, too. “Bulagaan na lang (you’ll just be surprised),” said one reporter assigned to cover the campaign. This made reporters more creative. The best technique, they found, was to search keywords on Facebook, for example “BBM Sara [insert date]” or “BBM-Sara [insert place.]” It also became a running joke that once reporters spotted many people in red, and vloggers would be seen with three phones on a rig, chances are they were were in the right place.

Even the Uniteam ID did not always guarantee access.

In Quezon City, the local organizers of mayoral candidate Mike Defensor allowed journalists to enter, but it was Marcos’ media officers who tried to block entry. It was in that Defensor-Uniteam rally on April 13 that Marcos’ media officer grabbed my wrists and covered my smartphone with her hands (I have a Uniteam ID). Minutes later, one of Marcos’ bulky male guards pinned me to a scaffolding just as I was in the middle of asking a question.

PSG securing Marcos?

Marcos’ security detail did not hesitate to physically block reporters from getting near him, with a reporter noting that they’re even more aggressive than the Presidential Security Group (PSG) detailed to vice presidential candidate Sara Duterte, who, as the President’s daughter, is entitled to PSG security.

In at least two campaign sorties which Marcos attended without Duterte, we got it on good authority that PSG members were deployed to secure Marcos, which is not allowed by PSG rules. A particular sortie in Paniqui, Tarlac, April 2, showed at least one PSG officer serving as a close-in security for Marcos. We were shown a photo of this officer, whom we have also identified, but we are not releasing it pending PSG’s response to our query.

Those swarming Marcos even dictate questions to reporters, according to another reporter, or they tell media what not to ask.

Rodriguez also had a habit of calling up reporters mainly to complain about the questions they asked. In the latter part of the campaign period, Rodriguez was no longer visible during sorties, so media had to settle for his statements posted on his Facebook page.

Another reporter observed: If you try to ask Marcos soft questions, like how he is, and what he thought of the area he just visited, his guards would relax. But the moment you shoot even mildly difficult questions such as if he was going to attend the debates, his guards will start roughing up.

It’s as if the questions are threats to Marcos’ life, quipped another.

Then again, reporters were gifted with crumbs once in a while.

Marcos agreed to an ambush interview during his Tagaytay sortie on March 22, but it was hush-hush. Several reporters had no clue. The Rappler team, after we learned of the venue, ran uphill to catch the candidate, as traffic was slow-moving. It was during that brief interview where Marcos laughed and walked away when he was asked if he or his family had paid their P203 billion estate tax.

Still, this didn’t stop journalists from trying.

BBC’s Johnson managed to ask Marcos at his Batangas rally on April 20: “Can you be a good president if you don’t answer serious questions?” His footage has, as of writing, been viewed 1.5 million times, and retweeted 26,000 times.

“If I came across as being aggressive, it wasn’t intended to be that way. In the end, the trolls changed the message to deflect, I believe, from the question I was asking,” said Johnson.

The common thread in the vicious attacks against Johnson after that incident was painting foreign media as threats to our sovereignty, which is straight out of the Duterte playbook.

One of the hate messages sent to Johnson was, “I just hope that someday, someone will slash your neck.”

If Marcos wins without facing the independent press, “legitimate journalists cannot be faulted for not trying,” said Esguerra.

“I would rather blame those who got the opportunity to sit down with him but didn’t raise the real issues both with vigor and rigor. Blame also media owners and newsroom managers who have been censoring their own journalists because they expect Marcos Jr. to win,” Esguerra added.

PSG securing Marcos?

Marcos’ security detail did not hesitate to physically block reporters from getting near him, with a reporter noting that they’re even more aggressive than the Presidential Security Group (PSG) detailed to vice presidential candidate Sara Duterte, who, as the President’s daughter, is entitled to PSG security.

In at least two campaign sorties which Marcos attended without Duterte, we got it on good authority that PSG members were deployed to secure Marcos, which is not allowed by PSG rules. A particular sortie in Paniqui, Tarlac, April 2, showed at least one PSG officer serving as a close-in security for Marcos. We were shown a photo of this officer, whom we have also identified, but we are not releasing it pending PSG’s response to our query.

Those swarming Marcos even dictate questions to reporters, according to another reporter, or they tell media what not to ask.

Rodriguez also had a habit of calling up reporters mainly to complain about the questions they asked. In the latter part of the campaign period, Rodriguez was no longer visible during sorties, so media had to settle for his statements posted on his Facebook page.

Another reporter observed: If you try to ask Marcos soft questions, like how he is, and what he thought of the area he just visited, his guards would relax. But the moment you shoot even mildly difficult questions such as if he was going to attend the debates, his guards will start roughing up.

It’s as if the questions are threats to Marcos’ life, quipped another.

Then again, reporters were gifted with crumbs once in a while.

Marcos agreed to an ambush interview during his Tagaytay sortie on March 22, but it was hush-hush. Several reporters had no clue. The Rappler team, after we learned of the venue, ran uphill to catch the candidate, as traffic was slow-moving. It was during that brief interview where Marcos laughed and walked away when he was asked if he or his family had paid their P203 billion estate tax.

Still, this didn’t stop journalists from trying.

BBC’s Johnson managed to ask Marcos at his Batangas rally on April 20: “Can you be a good president if you don’t answer serious questions?” His footage has, as of writing, been viewed 1.5 million times, and retweeted 26,000 times.

“If I came across as being aggressive, it wasn’t intended to be that way. In the end, the trolls changed the message to deflect, I believe, from the question I was asking,” said Johnson.

The common thread in the vicious attacks against Johnson after that incident was painting foreign media as threats to our sovereignty, which is straight out of the Duterte playbook.

One of the hate messages sent to Johnson was, “I just hope that someday, someone will slash your neck.”

If Marcos wins without facing the independent press, “legitimate journalists cannot be faulted for not trying,” said Esguerra.

“I would rather blame those who got the opportunity to sit down with him but didn’t raise the real issues both with vigor and rigor. Blame also media owners and newsroom managers who have been censoring their own journalists because they expect Marcos Jr. to win,” Esguerra added.

‘Show me one troll’

Reporters who were critical of Marcos and his campaign were subjected to online attacks, prompting FOCAP to release a statement out of “grave concern” that their members were being targeted by “supporters of Marcos. Johnson, himself trolled, said it was the same pattern of trolling he experienced for critically reporting on the Duterte government.

“It blasted for a week, ramped up very quickly. All of my social media accounts were flooded by comments, some of them threatening, death threats, lots of the same language repeated, which made it feel not very organic, like it’s coming from a script,” said Johnson.

This reporter was red-tagged in April, and there was a surge of Twitter comments coming from the same accounts after Rappler posted the footage of Marcos’ media officer and guard being rough on the journalist.

Esguerra said that his interviews with Marcos allies on his former show on the ABS-CBN News Channel, “were used to troll me on social media.”

But whenever he is asked, Marcos denies he has a troll farm, and always says, “show me one troll.”

Twitter had taken down a network of accounts spreading pro-Marcos content, and Filipino researchers have found that Marcos is the biggest beneficiary of fake news, including on TikTok.

“I’ve obviously been trolled on a massive scale, so it’s interesting for him to say he’s not aware of any trolling on his behalf, because it really does exist,” said Johnson.

Repeat a lie

Marcos has a tendency to keep repeating a lie. He has repeated in his vlogs that media does not cover him, which is downright false. He also insists that he earned a degree from Oxford University in England, when Oxford itself has clarified what he obtained was a mere special diploma that is not in any way equivalent to a degree.

The vloggers repeat the propaganda: they harp on Martial Law being the golden era, and lead discussions on why the Marcoses are not corrupt.

“He gets away with it, in large part, because of this massive disinformation infrastructure he has built around himself. Even if he evades real journalists, his vloggers can easily do damage control, mainly by gaslighting and attacking journalists,” said Esguerra.

In an interview with CNN Philippines, one of the very few he granted, Marcos claimed he was easily accessible to reporters, creating another inside joke that probably that was true if you were to ask him, “How are you?”

During the next rally after the CNN interview, in Pampanga on April 30, reporters managed to get backstage to put that claim to the test. But his media officers and guards tried so hard to keep him away from reporters they even took him to a tent for a few minutes, before making the run for his car.

This reporter managed to yell to him: “You said it is easy to interview you, we just have a few questions,” but he didn’t answer, much less look at who was asking.

TV5 reporter Marianne Enriquez got close and asked: If you are elected, what would you do to your P203 billion estate tax?

One of the people around Marcos told Enriquez: “Huwag niyo nang itanong ‘yung mga tanong na ganyan, ang sikip sikip na rito eh.” (Don’t ask questions like that, we’re already crowded here.)

The difference with father

Marcos’ father, the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr., shut down media and took over their assets. He issued an order that dictated to media companies to report only positive news. Journalists were arrested, detained, fired from their jobs.

The context of his son’s presidential bid is different. “It’s no longer withholding of information, no longer censorship as it was during Marcos’ time when there were literally censors sitting in newsrooms and saying you cannot do this because it was a very controlled media environment,” said veteran journalist Sheila Coronel in an interview with GMA News’ Howie Severino Podcast.

“It’s no longer controlling the flow of information, but flooding the information space with so much disinformation and untruths and propaganda, so people are no longer able able to discern what is fact and what is not,” added Coronel, who covered the dictatorship and is the former academic dean of the Columbia Journalism School in New York.

But Marcos the son has his own way of controlling the media, like the press conference in Cagayan de Oro where questions were screened one day ahead, and only select reporters were invited.

The Marcos team dangled access to reporters, and would even go as far as removing reporters they dislike from their mailing list where they send their press releases.

One time, a reporter asked Marcos’ media officer why they were excluded from the mailing list, and the media officer merely said: “Be kind.”

FOCAP said that these “restrictive actions… have sparked fears of how independent media would be treated under another possible Marcos presidency.” – Rappler.com