Aug 26, 2022, Inday Espina-Varona

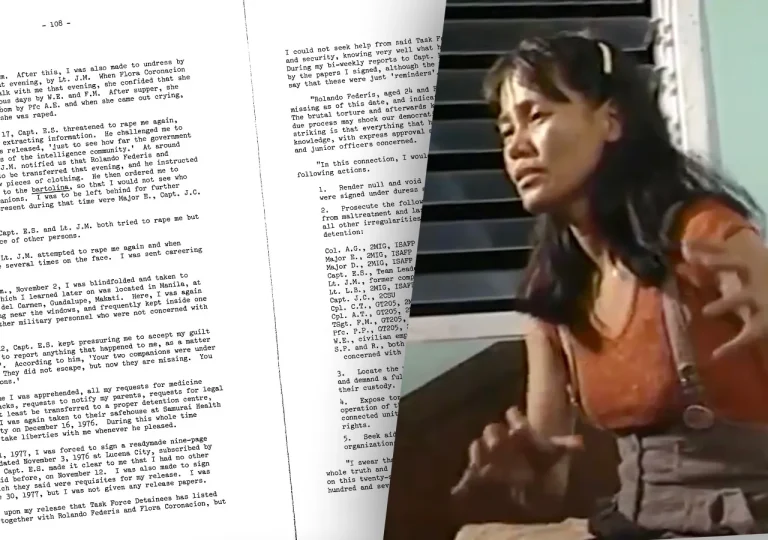

Despite the extreme abuse undergone by Adora Faye De Vera, interviewers always describe her as calm and steadfast

Commission on Higher Education (CHED) chief Prospero De Vera III’s brief statement on the arrest of his older sister, Adora Faye, was silent on her torture and rape under the Marcos dictatorship.

Her brother’s curt message following her arrest, announced on Thursday, August 25, ended with, “I fully support the administration of President Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos in its efforts to end the communist insurgency that has destroyed so many lives and properties.”

It said nothing about the sustained campaign of their parents, family and friends to demand the release of Adora when the military arrested her in 1976.

The military hid Adora Faye for half a year in military safehouses. They tortured and repeatedly raped her.

She survived only because she made the painful decision to limit the abuse via the “protection” forced on her by the officer in charge of the unit, according to a report by Gloria Esguerra Melencio for the Martial Law Files website, a joint project of the Philippine government, the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), and the United Nations Development Program, and Claimants 1081, Inc. – a group of human rights victims who got compensation for the Marcos-era atrocities.

Survival

Melencio told Rappler she interviewed Adora Faye, who was also called Dong, in 1998 for her undergraduate thesis on dissident women artists, including veterans of the earlier Hukbalahap insurgency.

By that time, Adora Faye had been released from her second incarceration in 1983, said Melencio.

“She had been wounded in an ambush, in her leg, and they brought her to V Luna, the military hospital in Quezon City to extract information,” the writer told Rappler.

The article delves into her 1976 arrest.

Melencio wrote: “Together with Rolando Morallos and Flora Coronacion, she was abducted and brought to a safe house, an old building that ‘looks like a beer house”, by the combined ununiformed forces of Military Intelligence Security Group, Constabulary Security Unit and 231st PC Company in Quezon province on 1 October 1976.

“Some 20 men stripped them naked, commanded them to run in circles, humiliated and interrogated them. The military asked Rolando to masturbate in front of Dong, which he refused. He was mauled and his genitals battered with a whip while the men laughed.”

Eleven soldiers and three civilians raped Dong and Flora continuously and forced them to remain naked for days.

One day, Dong woke up missing Rolando and Flora.

“They are now included in the long list of missing persons called desaparecidos or disappeared,” said Melencio.

Adora Faye’s December 1977 testimony to a domestic human rights group, passed on to Amnesty International, notes that she also never found her first husband, who also remains on the desaparecido list.

A copy of a 1983 Journal report in the #rememberML@40 page on Facebook acknowledged that Rolando and Flora were among “the disappeared”.

Grit

Released for a second time, Adora Faye took to legal activism and that’s when Melencio interviewed her.

“At that time ang paa nya puputulin na because of gangrene.” (She was suffering from gangrene and doctors told her they may have to amputate her leg.)

“She was fighting to save that, and had planned to go to Japan for extensive acupuncture treatment,” Melencio recalled.

“I don’t know what happened after that,” the writer added. “I kept the documentation for many years and told her during our interview that I would write about her after completing the thesis.”

Like many dissident mothers, Adora had to entrust her sons to relatives.

She told Melencio about the frequent tape recorded messages she sent home to a sister who served as guardian, in an effort to “have my son remember me”.

“All the while, she thought her son would know her, even just by voice. But at the hospital, she was surprised when her child called her “tita” (aunt),” the writer said.

“However, when I interviewed her, she was with her son, so they must have reunited as a family,” Melencio added, finding the chance with the CHR project.

A tweet by activist @BienSays shows an interview of Adora Faye recounting her ordeal and a narration that said her first arrest was actually a brief stint right after the declaration of Martial Law, for posting anti-government posters. The video shows her on a wheelchair, smiling, with two boys flanking her.

The tweet credits the video to a Cultural Center of the Philippines post on arthouse cinema films about martial law, but a check by Rappler showed it was no longer available.

A source from Panay island, who asked to remain anonymous, said Adora Faye walked with a pronounced limp.

“For many years, she was always on the order of battle of the military but not during the last five years,” added the source.

“Maybe she had retired. We heard she was suffering a lingering ailment linked to the torture and rape she experienced during the Marcos years, the source said.

Inspiration

But Adora, 68, is more than just a victim of brutality during martial law.

Human rights workers, feminists, and progressive artists also recognize the grit and steel behind the brokenness of a woman forced to survive the depravities of Marcos’ henchmen.

“This frail wisp of a woman has undergone extreme pain and anguish beyond any human being can imagine, yet she remains calm and steadfast. I promised her I would be writing her story and kept the documentation for many years. Now I have fulfilled that promise,” said Melencio in notes to her article.

Her poetry and life, and the works of other artists inspired by her life, are studied in the University of the Philippines in Women’s Studies classes.

Melencio shared one of Adora Faye’s poems, “Sabi niya, Siya raw ay aking Ina” (She said she was my mother), told from the point of view of a young boy, who could not recognize his mother, who tells him she will be brought to prison after release from hospital.

He shies away from her embrace, giving the excuse of not wanting to add to her injury. But he smiles and waves as he leaves, “Pagka’t gusto kong mawala ang namumuong luha/ Sa gilid ng mata/ Ng babaeng maputla/ Na nagsasabing/ Siya’y aking ina.”

(Because I wanted to stop the tears building on the sides of the eyes of this frail woman who says she’s is my mother.)

Rodolfo Vera’s harrowing play, “Indigo Child” gives a nod to the alleged rebel leader in its depiction of how torture scars can linger for decades, and how women fighting dictatorship can pay an especially high price for that struggle.

Vera told Rappler the second-place Palanca winner was fiction, in the sense that the female lead is depicted as wanting to forget the past that haunts her and is the cause of severe mental health problems. A former activist tipped him off about Adora Faye.

“I never met her, but her story inspired me. She did not lose her memory as far as I know, and probably only changed names for security reasons, but the rape and torture she suffered are documented,” he told Rappler.

The plot involves the son of Felisa, struggling with scars of a childhood sans a mother, coming to terms with his pain as she undergoes electroconvulsive therapy.

“Felisa reveals that her child’s father is her military rapist. That’s fiction. But I found a way to honor Adora,” the playwright said.

It is in the last line, where son Jerome confronts his ill father, wheelchair bound and suffering from diabetes-induced gangrene, and with barely any memory of the woman he abused.

“Lagi mong tandaan ang pangalan nya, hanggang mamatay ka… siya si Adora.” (Always remember her name until you die… she is Adora.)

Struggle

Activist Judy Taguiwalo describes Adora Faye as “a very talented poet whose poems deal with women’s oppression, state violence against women and the power of collective action.”

The poetry discussed in Taguiwalo’s class is “Anino ng Magsasaka”, from Bigkis: Mga Piling Akda, Gantimpalang Ani 1987-1991, published by Gapas Foundation Inc. and Philippine Peasant Institute in 1994.

‘Pinangulila ba ng langaylangayan

Yaong paglalaho ng langitngit-duyan,

Mga palupalo, palayok, kawali,

Tinig na umawit ng mga uyayi?

Sino ang umako sa mga gawain

Ni Tano nang bundok ay kanyang akyatin?

Sino’ng nagpatuloy maghasik ng butil

Matapos mapaslang si Pedro Pilapil?

The poem takes off from beloved activist anthems sung during and after martial law, and even today. Tano is a peasant who breaks after a series of injustice and takes to the hills. Pedro Pilapil is a farmer whose small piece of land is stolen by a rich, powerful man.

The poem talks of women taking up the struggle, facing authorities to save their men, organizing communities, even as they continue to serve spouses and children, and pound rice grains, weave baskets, and take care of the family’s animals. – Rappler.com