Kristine Joy Patag – Philstar.com

February 23, 2023

MANILA, Philippines — Making books for children means helping shape the individuals that they will become. In the Philippines, which has often been described as forgetful, storytellers for children have the task of making sure a pivotal moment in our history — the EDSA People Power Revolution that ousted a dictator and is touted to have restored democracy — too, becomes part of their foundation as future leaders.

Children’s book writer Rusell Molina believes that young Filipinos inherently embrace kindness, unity and love. And when they ask — and learn — about People Power, he would like them to remember it as a story of hope and courage.

If he was asked by Filipino learners why the EDSA commemoration is a holiday anyway, Molina hopes to give a definitive answer. “What do we tell them? Do we talk about reds or yellows or dark pasts and bleak futures? Or do we tell stories of hope, bravery, kapit-bisig (arm in arm) and flowers over tanks?”

He picks the latter. “I think children naturally embrace concepts of kindness, unity and love until an adult points them to a different direction,” he says in an e-mail to Philstar.com.

Augie Rivera’s “Isang Harding Papel,” illustrated by Rommel Joson, and Russell Molina’s “EDSA,” illustrated by Sergio Bumatay III are part of Adarna House’s #NeverAgain bundle.

In 2013, Molina wrote “EDSA,” a book with sparse text but accompanied by a gorgeous spread of whimsical illustrations of things related to the people’s peaceful revolt from the pen of Sergio Bumatay III.

In it, the children’s book writer aimed to share the story of EDSA through numbers of pivotal moments and characters in the event, until the Philippines reaches “isang ibong lumilipad sa taas ng EDSA. Nakatingin sa milyon-milyong taong ngayo’y malaya na.”

(A bird flies high over EDSA, looking at millions and millions of people who are now free.)

Bumatay, in a 2013 blog post, explained that he wanted the book’s illustrations to be “very special and memorable, just like the occasion itself.”

“The black and white drawings evoke nostalgia and vivid memories while a splash of yellow highlights the special color. To depict a sense of history, I thought of using the dioarama as format to stage the scenes and organize them inside a wooden box I made especially for this book,” Bumatay adds.

The book was published with help from the EDSA People Power Commission, which called it “a story our children must hear, for at EDSA, the world saw the best of the Filipino spirit.”

Taking root

Illustrator Rommel Joson remembers growing up with his classmates wearing election campaign headbands with a huge hand forming an L sign on their foreheads. He was seven.

It was a different childhood for writer Augie Rivera, whose book “Isang Harding Papel” was illustrated by Joson. Rivera says he was part of “that generation of Martial Law babies who grew up shielded from the realities of times,” a familiar story especially from children who grew up in the bailiwick of the Marcoses.

It was not until he went to the University of the Philippines, after EDSA, that he truly learned about the horrors of the Martial Law. “It was then that I was awakened to the truth and the part Martial Law played in our society and our history,” Rivera tells Philstar.com in an e-mail.

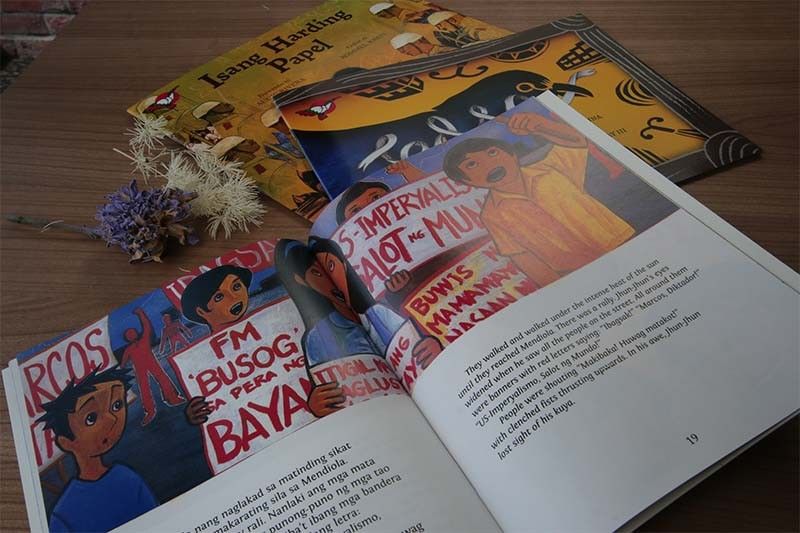

He has since written two Martial Law-themed children’s books. “Si Jhun-Jhun, Noong Bago Ideklara ang Batas Militar,” was published in 2001, as part of the UNICEF Philippines and Adarna House “Batang Historyador” series.

A spread from “Si Jhun-Jhun, Noong Bago Ideklara ang Batas Militar,” written by Augie Rivera and illustrated by Brian Vallesteros.

In it, protagonist Jhun-Jhun just wanted to know where his older brother had been going. Unknowingly, the child followed his brother to a rally with “men wearing shiny, round helmets” forming a barricade around the crowd. Next, there were gunshots and chaos. And all Jhun-Jhun found was his brother’s left slipper.

Rivera says the book was inspired by a photo he saw of “a street full of broken bottles, stones, and slippers — an aftermath of a violent rally dispersal.”

More than a decade later, Rivera wrote “Isang Harding Papel” in 2014, with Joson as its illustrator. Rivera shares that the story was loosely based on a cousin whose mother was a political detainee during Martial Law.

Both books are part of Adarna House’s #NeverAgain bundle.

Joson filled Rivera’s “Isang Harding Papel” with collage-like illustrations, a play on newspaper clippings and flower origami. One striking illustration is our protagonist Jenny, her grandmother Priming and her detained mother Chit enjoying a spread inside the police headquarters with big smiles on their faces.

At the upper corners of the drawing, two pairs of boots are seen — an apt frame that paints the rest of the story where the fear looms over a child’s joy of being with her family.

Part of the accompanying text story of that illustration was Jenny asking her mother, out of nowhere, why is she detained anyway?

“Paano, ‘pag may rally, lahat ng pinapalabas naming mga dula sa kalye, laban kay Marcos. Hindi niya siguro nagustuhan,” Chit had told her daughter.

(Well, when there is a rally, our street theater is against Marcos. Maybe he didn’t appreciate it.)

‘Propaganda’

Joson, in a blogpost in 2014, shared that he dedicated much research work depicting the EDSA highway in “Isang Harding Papel”: “What did the old propaganda billboards of President Marcos and Imelda Marcos look like?”

He knows that as an illustrator, and of historical fiction for children at that, it is important to “present historical events in uniquely engaging ways.”

Illustration by Rommel Joson for Augie Rivera’s “Isang Harding Papel.”

Fast forward to 2022, Joson’s illustration, and Rivera’s and Molina’s stories were labelled propaganda meant to radicalize children against the government. National Intelligence Coordinating Agency Director-General Alex Monteagudo claimed with no basis that these were linked to the communist rebels..

This came after the Adarna House, a Filipino household name for publishing house for children, released its #NeverAgain bundle after the 2022 national elections that, at that time, showed candidate Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., namesake and only son of the ousted dictator, inching towards Malacañang.

Rivera, then, condemned Monteaguado’s baseless red-tagging of the publishing house. “As ‘historical fiction,’ this features stories of adventures and the awakening of the youth and important events and lessons of our history,” he wrote in Filipino in a Facebook post.

He tells Philstar.com now that the experience was “quite unsettling to say the least.”

Rivera, now current head writer of AHA!, an infotainment program and writer for the top-rating gameshow, Family Feud, said that “nobody wants that for themselves or their family.”

But Rivera knows that once a book has been published, what happens next is out of the hands of the writer. Even if his book is labelled propaganda, he knows he cannot dictate how people should react to it.

“That’s how democracy works. What’s most important to me is that the book is read, and hopefully resonates with my intended audience,” he says.

It was, again, a different story during the Martial Law era of Marcos Sr. In the first week of dictatorial rule, the president issued a Letter of Instruction on the “prevention of the use of privately owned media facilities and communications.”

This authorized the military takeover of assets of ABS-CBN, Associated Broadcasting Corp. and other stations, as accounted by the Martial Law Museum in its website. It said that the sequestered assets were being used for “propaganda purposes against the government.”

Never again

Illustrator Joson admits it is difficult to fathom how his book would have been labelled as propaganda, especially since “Isang Harding Papel” was based loosely on a real-life experience and he too grew up in the wake of EDSA.

“A big part of the stuff and stories I grew up with informed illustration research and process. When I was a child my grandfather gave me a coin with Marcos’ likeness on it — which was unbelievable to me,” Joson says, adding that: “Seeing how the tide of public opinion is shifting is incredible to me.”

“I think denying the abuses perpetrated during Martial Law is a slap to those who suffered during this time,” Joson says.

Rivera says that the “Batang Historyador” series was conceptualized as a supplementary reading material for teaching history.

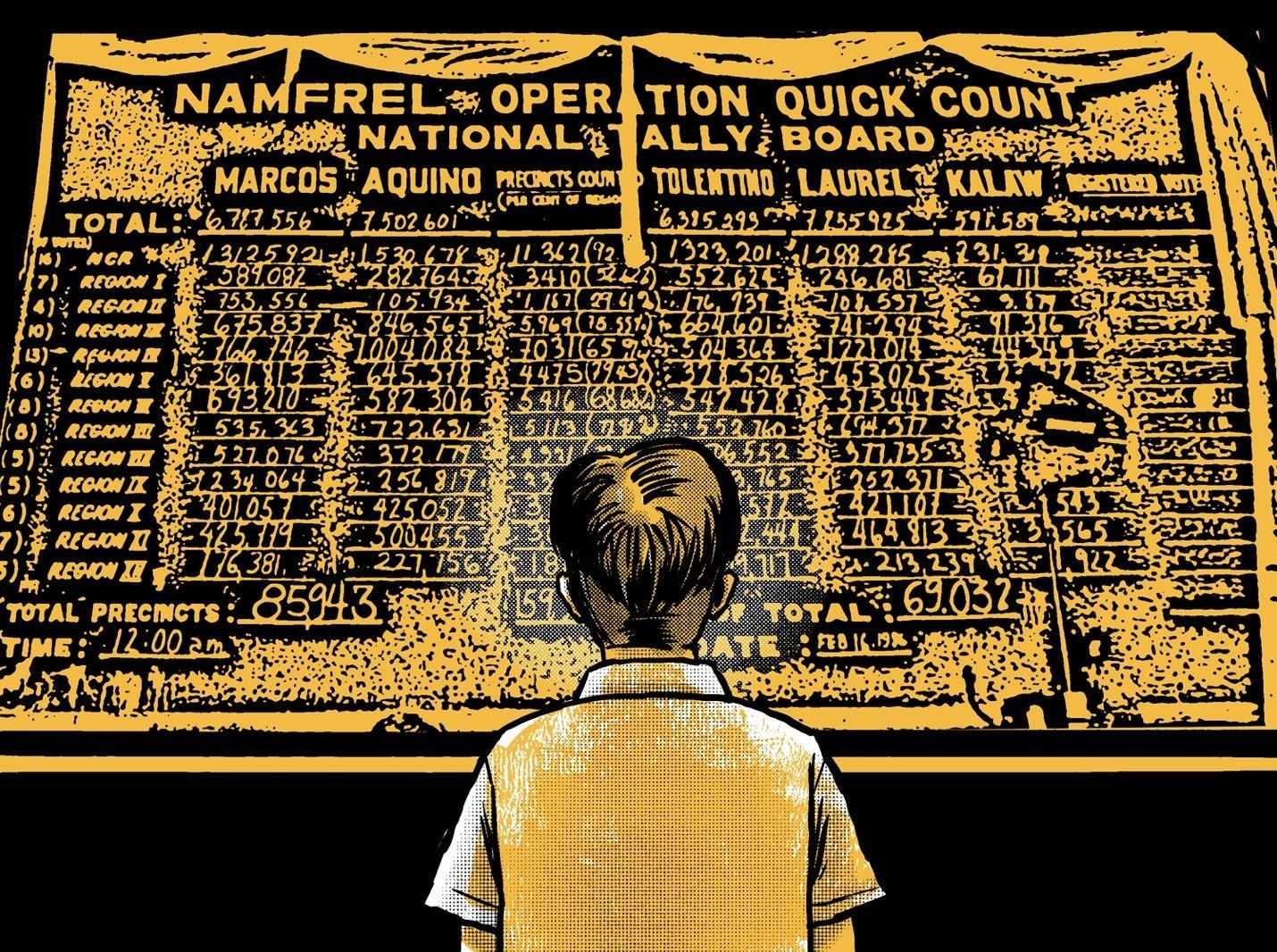

Rommel Joson shares with Philstar.com an illustration that shows one of his childhood memories. He says when he was in high school, “the blackboard tallying the NAMFREL quick count results was displayed in school, so I saw it every day.”

The Martial Law Museum, a project by the Ateneo de Manila University, has opened a digital library for those who want to learn about this period in our history, from the beginning, duration, end and lessons of Martial Law. It also offers teaching resources, in English and Filipino, and filmed online lectures.

After all, learning history is beyond memorization. “Another way to go about it, to make history ‘come alive’ is through stories and personal accounts from primary sources, and even historical fiction,” Rivera says.

It is a tough job but one that needs to be done, he admits. The Philippines’ Martial Law era can never be told without abuses, disappearances, torture, dread and killings. Thousands of Filipinos suffered through long years of fear under the Marcos’ dictatorial rule.

“It was quite inevitable. What I did then was to focus more on the characters, and make them more believable, relatable, and child-like, so other children could easily empathize with them,” he says.

Rivera continues: “Through their stories, we hope the child reader would get curious and want to know more about history and the conditions and struggles of children during these most difficult periods in our nation’s past.”

Joson knows that teaching history, including the EDSA revolution, is essential, especially since no one wants to repeat that dark period of our history.

With the young generation becoming increasingly visual, the illustrator says “[n]ow more than ever, we have to reclaim the child’s visual landscape and bend it towards things that are factual and true.”

Molina, whose book “EDSA” featured captivating and strong visuals, says he wrote the book with highly visual narrative “to become an avenue for an adult-child shared experience.”

As it offers a different reading experience with text-heavy books, Molina hopes that his book elevate the child-reader’s. “And with this lens, EDSA becomes more than just a history picture book but a platform for new discoveries and continued conversations between generation,” he adds.

After all, children should always be part of discussions of issues and challenges in society, because they too are affected, Rivera says.

“We want our children to learn from past mistakes. And never forget. We want them to become critical and ask about complex issues, and we want to make them care enough to dream, aspire, and participate in creating better world for them to live in,” he continues.

But in a world where misinformation and disinformation proliferate and even historical accounts are cast in doubt, what do children’s story book artists have left to do?

“I guess we just have to tell and share our stories over and over again.”