Written by Anna Bueno, Updated Apr 1, 2020

Manila (CNN Philippines Life) — As the Philippines reels from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, several groups of artists, engineers, designers, and volunteers have stepped up to provide much-needed creative solutions to gaps in problem-solving brought about by the crisis.

The challenge was this: in the face of medical supply shortages, delayed interventions, and bureaucratic red tape, among others, what alternatives are immediately available at our disposal?

Amid the noise, and despite national government efforts that may leave more Filipinos more scared than reassured, creators and innovators have acted quickly to quell the crisis in their own communities, and even beyond. CNN Philippines Life got in touch with several volunteer groups with out-of-the-box interventions that may give us more reasons to hope, and to imagine a renewed future shaped by the lessons of these trying times.

‘Coronavirus, matatalo natin!’

In Brgy. Bagong Silang, Quezon City, and Brgy. Bignay, Valenzuela, women and children hand out and post COVID-19 flyers in communities that lack access to reliable information about the pandemic. The flyers are in Filipino, featuring encouraging messages and warm illustrations.

The flyers were made available for free online by Citizen’s Urgent Response to End COVID-19 (CURE COVID), a multi-sectoral people’s initiative formed to respond to the needs of these communities, and were designed by a volunteer group including Karl Castro, an artist and graphic designer who created the initiative’s visual identity.

“The goal was really to try and translate the complex information into easy-to-understand, visual, and vernacular language,” says Castro. “I wanted it to be less like the cold data and announcements we get from media and the government, hence the rounded forms.”

Most information and educational communication (IEC) materials about COVID-19 are predominantly in English. Many are designed to be attention-catching, using bold and bright colors and typefaces, which may be more panic-inducing than reassuring.

Castro’s design — along with the translation in the material — addresses these issues. The CURE COVID team did more than simply translate information from the Department of Health and World Health Organization from English to Filipino. Translation, says Castro, “requires one to really be present and interrogate the source text.” His task was not only to translate the text, but also to translate textual content to visual content.

In both cases, the content is not limited to health implications of the spread of the virus. The approach is rights-based, where not only bodies are protected, but also communities and basic rights.

This kind of work is almost as critical as the solutions themselves, according to Castro. “Communication and cultural work are shadow areas which do not seem of primary importance during these times of crises, but are actually the vessels which hold the power to inform, placate, reassure, inspire,” he says.

Lockdown laboratory

In Cainta, Rizal, Czyka Tumaliuan, a writer and curator, and Rex Irineo, a director of a business intelligence and technology firm, sought to find a way to minimize transmission right at home. They came up with Lockdown Lab, a think tank and interdisciplinary community brainstorming open source designs and hacks against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The team has consultants and members from different industries, spanning industrial design, physics, chemistry, arts, philosophy, political science, the circular economy, educational technology, entrepreneurship, law, engineering, media, software development, AI, and healthcare.

Anyone who is interested in research, design, and contributing interventions to avert the effects of the pandemic is free to like Lockdown Lab’s public page, which will be a learning portal where homegrown open-source solutions devised in the private group are shared, says Katrina Olan, who handles communications for the group.

The intent is that ideas pitched in the public group may be incubated further in the private group. “For open-source designs to make an impact, it has to be two-way,” Olan says. “It needs to be continually evolving. We have to help each other build and grow the idea.”

As of date, the lab has a number of ongoing projects, including prototype development for sanitation boxes, tools for distant vital signs monitoring, touchless elevator buttons, low-cost ventilators, and a video-conferencing initiative. Volunteers also participate in distribution and donation efforts for PPEs.

The touchless elevator buttons project — which was the project that sparked the creation of Lockdown Lab — is currently in the design phase. “We wanted to showcase that this could be done, and share our open-source work to everyone,” Irineo says. “This should spark a revolution that contactless sensors should be everywhere to mitigate the transfer of microbes in our daily interactions with things.”

Yet hacks and open source solutions “are practically makeshifts or just substitutes, [and] they may not be as effective as the branded products and aren’t medical grade,” says Irineo. “But still, better to have something than nothing. And it’s easy to make.”

Lockdown Lab is ultimately in the business of retooling and improvising systems and ways of thinking. “This pandemic is urging us to unlearn, rethink and re-imagine how we deal with solving problems not only in healthcare, but in all industries,” says Tumaliuan. “We urge more experts to be open in sharing what they know in people who are willing to help in the lab.”

Fashion that saves lives

All over greater Metro Manila, fashion designers and seamstresses, among them Rio Estuar, continually develop reusable masks made from accessible and eco-friendly materials. Estuar is the mind behind RIOtaso, a sustainable clothing startup that creates bags, tops, outerwear, headwear, and now masks made of scrap fabric.

Before the quarantine, Estuar researched on reusable mask designs which effectively filtered tiny particles that may get through standard cloth masks. Her initial design featured a tissue insert opening between two layers of non-woven fabric.

An introduction to fashion designer Santi Obcena led Estuar to adopt a new design, which features filters sourced from eco-bags and umbrellas, a waterproof and fully lined outer layer, and a cotton filter pocket. “[The] design suggests that these materials mimic that of surgical masks given the waterproof front and the filter,” Estuar says.

The masks remain a work in progress; any data to create better and more effective masks to provide to frontliners is welcome. “We are looking into talking to people in the medical field to figure out how else to create more effective masks, taking into consideration safety and comfort,” says Estuar.

On top of managing RIOtaso, Estuar also provides a free mask to delivery riders for every purchase of goods on the online shop. Now more than ever, she says, people need to pool their skills to address inadequate medical supplies — or to simply protect each other.

“I’ve seen online designers of different fields printing face shields, fashion designers coming together to design effective protective gear, chefs creating dishes for donations and all that,” she says. “Our coming together in times like this is the very definition of bayanihan.”

Service by design

From the University of the Philippines Diliman, a group of industrial designers, chemists, and engineers banded together online to create SaniTents PH, a crisis response project to develop open source, affordable, and easy-to-build sanitation tents that will minimize the risk and transmission of the SARS-Cov-2 virus.

The team is composed of industrial designers, chemists, and engineers from the College of Fine Arts, College of Science, and College of Engineering. “Among these professions,” says Keeshia Leyran, the team’s design coordinator, “there is one that most Filipinos have not heard about — industrial design.”

Simply, industrial design involves designing products and systems to make everyday lives better — even as it is an “undervalued, underutilized, and underappreciated profession here in the country,” she adds.

“The initial plan was simple,” says Leyran. “We make a design; we make it available. We tap a few friends with contacts to LGUs so that they can implement it faster.”

The team released the design in tranches: first, the booth design (made of PVC pipes and plastic cover); second, the diffuser design (with a standard knapsack sprayer with modified nozzle); and lastly, instructions to implement the full design along with the chemical disinfectant solution (as the solution cannot be prepared by non-professionals), now all free for download online. “We made sure that the materials used in the design were easy to source given the problems that may arise in procurement and distribution during the lockdown,” says Leyran.

Simultaneously, the group has been recruiting volunteer chemists, chemical technicians, chemical engineers, biologists, and molecular biology and biotechnology graduates to help interested LGUs from all over the Philippines set up the tents. At some point, the number of volunteers who signed up, within 48 hours, reached 3,000.

The enthusiastic response for SaniTents PH proves that industrial designers and makers must be given seats at the policy-making table, in line with an interdisciplinary approach to problem-solving.

Leyran adds: “We have industrial designers like us building decontamination tents and makeshift face shields. We also have fashion designers who developed designs for protective suits for our health workers. We also have people from the maker movement — those with 3D printers and laser cutters, fablabs all over the country — producing parts for face shields round the clock. It is obvious that this untapped industry has a lot to offer for our country.”

Which is not to say that what the SaniTents PH team has accomplished so far is due only to their expertise. “Honestly, none of the private initiatives I see online is rocket science. Even what we did with SaniTents isn’t rocket science,” Leyran says. “We just really need someone to initiate and take action. Luckily, for SaniTents, August [Patacsil] did.”

“With the right manpower and experts working on it,” she adds, “creating solutions can be easier. All we really need to do is think about what the people need—what our front liners need — and act as soon as possible.”

‘These vegetables will not walk on their own’

In Quezon City, creative and knowledge workers group Sama-samang Artista para sa Kilusang Agraryo (SAKA) call for free mass testing and remain critical of the government via creative protests despite quarantine limits.

On March 27, members voiced their call for the safe passage of farmers and agricultural workers through checkpoints heavily guarded by police and military. Taking their cue from agitprop installations, members placed pieces of vegetables in streets, and using chalk, drew legs on them as if to depict the vegetable walking. “HINDI BUMIBIYAHE ANG GULAY MAG-ISA,” says the message with the drawings.

“The lockdown has made it difficult for farmers to travel to their farms and bring their produce to markets and city centers,” says SAKA’s Angelo Suarez. “This reveals how undeveloped the value chain is for agriculture.”

SAKA also participates in relief efforts for disadvantaged communities in addition to staging creative protests. The group acknowledges the risks involved, but ensures physical distancing measures, among others, are followed.

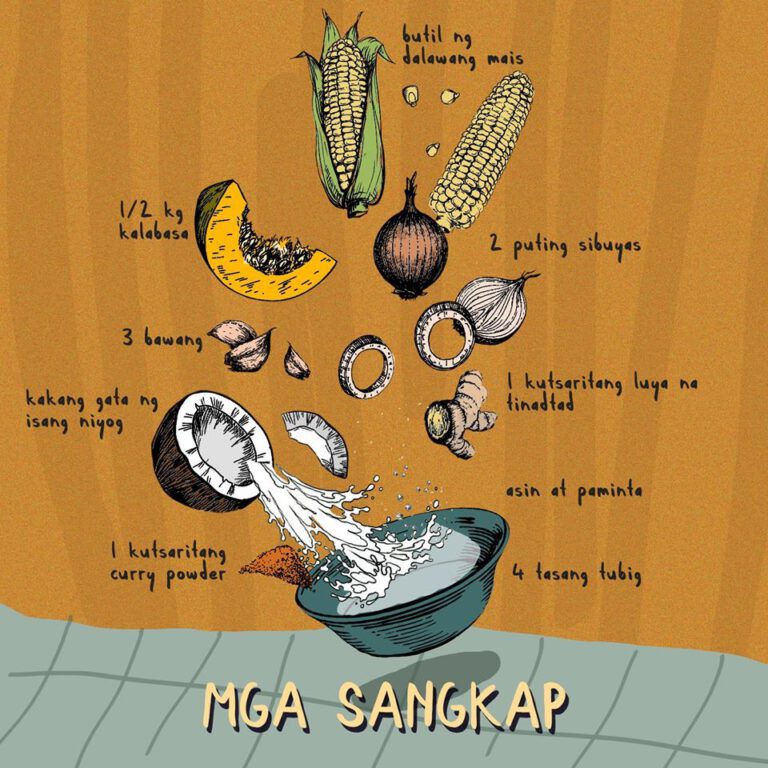

The group found that even in simple grocery or market errands, protest is possible via sandwich boards (worn around the body) and bayongs inscribed with the words “Free mass testing now.” Via its Facebook group, SAKA also released a recipe series titled “Kitchen Kalasag” with food illustrations of “easy-to-make” recipes, which members plan to reproduce into pamphlets for vulnerable communities.

But creativity and innovative interventions should not stop there. For SAKA, creativity goes into reimagining the very system which justifies the need for these interventions even outside the context of a crisis. Suarez says: “We need to mobilize our creativity to fight back — not only against the disease, but against a state that has abandoned us to this disease, against a social order that prevents us from creating mechanisms for protecting each other and our interests, against the ruling classes who will try to take advantage of anything — even a pandemic — to exploit the workers and peasants who make up the majority of our people.”#