A Book Review

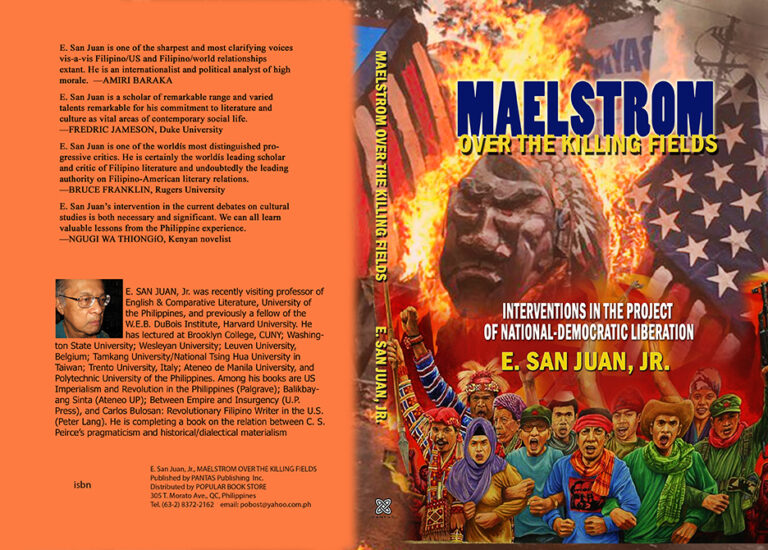

[Published by Pantas Press, 2021, distributed by Popular Book Store, Quezon City]

By Paulino Lim, Jr.

Emeritus Professor of English California State University, Long Beach

______

From one who has written innumerable books, this volume may be viewed as an “anthology of San Juan’s best essays.” It has a powerful voice that stirs the maelstrom over “the killing fields,” a metaphor that came out of the Vietnam War (1955-1975), and most apt for the Philippines, where the first killing fields took place when the U.S. military fought and conquered the insurgents and proceeded to colonize the country (1899-1912).

The anthology presents an “agenda for change and social transformation.” It focuses on particular themes, situations and personages, e.g. the diaspora, pandemic, Jose Rizal and Nick Joaquin. (Was Rizal gay? How do you account for Joaquin’s “tragic-comic consciousness?) In each essay San Juan goes deep into the subject, deploying various analytical tools drawn from history, philosophy and literary criticism, and synthesizes the findings into a coherent “knowledge” or information about the subject. The new information may add, amplify, or revise previously known “facts,” but does it constitute Truth? Is the latest interpretation analogous to the self-portraits that the artist paints in the course of his life? It is up to the reader to decide.

A critical tool that San Juan includes in the analysis is the “structure of feeling” that informs not only the interpretation or criticism itself but also the attitude of the critic himself–a technique he adopted from Charles Sanders Peirce credited in the. Acknowledgements. In fiction, laying the feelings of a narrative is the equivalent ofs scoring a film with music.

A simple exercise is to define the feeling of some elements of the Preface. San Juan calls in awe the pandemic as a “planetary upheaval”; condemns the exploitation by “rapacious” capitalists–with the aid of Karl Marx. (i) He mourns the death in 2020 of 67 Filipino nurses ministering to Covid-19 patients. He recalls with

muted pride the militant Filipino presence in the U.S. that marked the four-day riots in Watsonville, California, in December 1929. The event prefigured the violence against Asians, Filipinos included, being blamed for importing the virus from Wu Han.

What convinces the reader as in the case of Rizal and Joaquin, for instance, , is San Juan’s close reading of the author’s works (poems, essays and novels) and tracing the development of his “sensibility” reflected in the work. San Juan’s final word on Rizal is that he was “not a messiah, only a prophetic intellectual of colonized peoples “ San Juan recalls James Michener’s remark that Rizal’s novels were “directly responsible for the author’s death.” San Juan sums up Rizal’s challenge for Filipinos to “fight and win their independence by their own sacrifices.” The essay ends with a passage from “Mi Ultimo Adios.”

I die when I see the dawn break,

Through the gloom of night, to herald the day;o And if color is lacking my blood thou shalt take Pour’d out at need for thy dear sake,

To dye with its crimson the waking ray. (89)

What entertains the reader are the human-interest and gossipy details, embellished by San Juan’s often sardonic comments. Rizal’s Austrian correspondent Ferdinand Blumentritt tries to console him: “. . . but you are one of the heroes who conquer pain from a wound inflicted by women. (64) He met in 1888 a 22-year-old O-Sei-San, a samurai’s daughter, “may have experienced carnal bliss.” (65) The historian Ambeth Ocampo has interpreted the recurrence of snakes as phallic symbols in Rizal’s dreams, suggesting that Rizal may have been a closet gay. (66) Rizal performed a common-law marriage ceremony with the “wandering swallow” Josephine Bracken by holding hands together and marrying themselves. The Catholic priest Father Obach refused to marry them. (67)

Of particular interest to me is the discourse on the Filipino diaspora. I write as an OFW (overseas Filipino worker/writer), the largest segment of the Filipino diaspora. (The discourse provides a prospectus for M.A. and Ph.D., defining six “theses” to pursue.) I am glad I am not writing in Myanmar (I am three-fourths Malayan) or in Hong Kong (one-fourth Chinese). I read Maelstrom during Advent anticipating the birth of Christ. What we got instead was the “second coming” of Covid-19. Nonetheless, I took Communion to celebrate the presence, and the

booster shot to ward off the pandemic. The pandemic has introduced new modes of learning, done away with SAT and college entrance exams, re-examined Ethnic and Women’s Studies, as Delia V. Aguilar explores in the Afterword. (201)

San Juan’s review of the colonization and decolonization of the Philippines has been a welcomed corrective to my naive reading of the country’s history. The structure of my feelings was centered on gratitude. Gratitude to Spain for bringing the Roman alphabet and the Catholic Religion; to America for introducing democracy, public education, and English–the lingua franca of the world and the Internet; and to Japan, after repulsion by the atrocities the military inflicted in the Bataan Death March, for Buddhism, calligraphy, and the films of Ozu and Kurosawa.

In San Juan’s capsule review, “The history of the Philippines may be read asseculaone long chronicle of the people’s struggle against colonialism and imperialism for the sake of affirming human dignity and universal justice.

Gratitude still centers my feelings toward the U.S., despite the white supremacy movement and the “Big Lie” of the 2020 Presidential Elections being. Stolen. UCLA exempted me from paying the $600 out-of-state tuition fee; now it runs to about $32,000. San Juan earned his bachelor’s degree in English at the secular University of the Philippines, modeled after the U.S. state university system. I attended the Dominican University of Santo Tomas, Manila, with its compulsory Scholastic curriculum requiring courses in Ethics, Cosmology, . And two semesters of Logic. This prepared me for writing term papers in my UCLA graduate courses in Linguistics, Drama, and American, Romantic and Victorian Literatures. (I did my Ph.D. dissertation on Byron).

Teaching at California State University, Long Beach, gave me time to research and write. I wrote four interrelated novels dealing with the Marcos Dictatorship that I call, perhaps inordinately, “The Philippine Quartet.” It is an homage to Lawrence Durrell whose Alexandria Quartette fascinated me as an undergraduate. In the first novel Tiger Orchids on Mount Mayon, the protagonist Mark is a surrogate for Marx. Mark studied at U.P., joined the teach-ins conducted by the Marxist professor Saldivar and read Mao Tse Tung’s

Red Book.

In Maelstrom over the Killing Fields, San Juan persuades Filipinos in the homeland and in the diaspora to act on an agenda for change and social transformation. No other Filipino approaches his scholarly output and world-wide

stature as an intellectual. I honor him, as I do the journalist Maria Ressa–the first Filipino to win a Nobel Peace Prize. There is so much love in what he writes, so much light in what he says —###