It has been over 130 days since the start of COVID-19 lockdowns,

yet government help for families most affected by the crisis remains

snail-paced, measly, and even much less than promised.

The inadequacy of the Social Amelioration Program (SAP)

underscores the government’s failure to address the plight of the most

vulnerable Filipinos in the time of COVID-19. The Duterte administration’s hype

that it is close to completing the distribution of the second tranche of SAP

also conceals how many Filipinos will not get aid that they still badly need.

Lockdowns have been extended in many areas because COVID-19

continues to spread so economic activity is resuming unevenly. However, too little

is being done to protect millions of families from the prolonged joblessness

and loss of incomes.

The Bayanihan to Heal as One law promised to give emergency

cash subsidies to 18 million low-income families from vulnerable sectors whose

jobs and incomes were disrupted by the COVID-19 lockdown. The SAP was supposed

to give Php5,000-8,000 per month for two months. The number of target

beneficiary households was originally identified at 17,741,405 by the

Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD). Its Memorandum 14-2020

later added another five million needy families to receive aid – also called

wait-listed families – which brought the total number of SAP beneficiaries to

22.7 million.

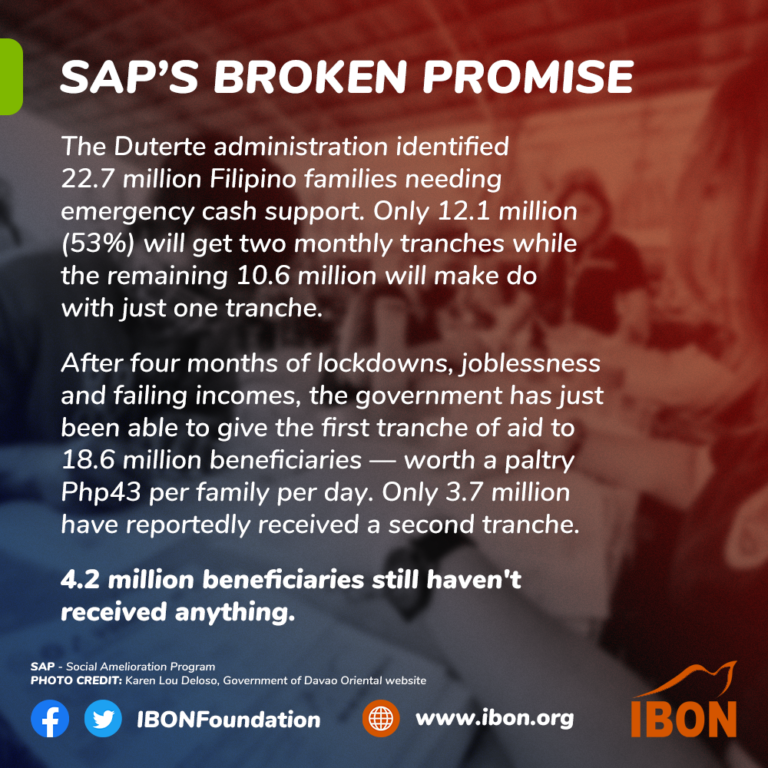

Broken promise. The burst of generosity was not as

it seemed. As it turns out, 10.6 million or almost half (47%) of the 22.7

million beneficiaries will only get one of the two promised tranches. The

government backtracked and eventually said that residents of areas declared

under general community quarantine (GCQ) or modified GCQ as of June 15 would

not be getting the second wave of aid after all.

Consequently, only 12.1 million or a little over half (53%) of SAP

beneficiaries residing in enhanced/modified enhanced community quarantine

(ECQ/MECQ) areas will get both tranches. This includes 8.6 million households

in Region 3 (except Aurora), National Capital Region (NCR), Calabarzon,

Benguet, Pangasinan, Ilo-ilo, Cebu province, Bacolod City, Davao City,

Albay province, and Zamboanga City. Also, only 3.5 million of the wait-listed

families are covered.

The government is supposed to have already spent Php374.9 billion

for COVID-19 response of which Php200.9 billion went to the DSWD, Php12.5

billion to the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE), and Php11 billion to the

Department of Agriculture (DA). Has everyone in need been helped?

Overdue. Aid is actually very slow in coming, according to data as of July 22. Although some 17.45 million beneficiaries were able to get their first tranche the majority had to wait at least 6-10 weeks for this.

Of these, 3.7 million or 31% of the target 12.1 million reportedly

also already received their second SAP tranche. Malacañang said that 80% of

those supposed to receive a second tranche will get the amount before the end

of July. This is very late though. Beneficiaries presumably should have gotten

their first tranche around mid-April, or a month into the lockdowns, and the

second tranche correspondingly by mid-May. Receiving the second tranche only

now is over two months late.

But these late recipients are actually the lucky ones. As of July

22 or over four months of lockdowns, around 4.18 million still haven’t received

anything – 288,637 from the initial 17.7 million target beneficiaries, and

based on reports, 3.9 million of the five million wait-listed families. This

sadly includes 62,509 Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps)

beneficiaries who are among the poorest of the poor in the country.

Inadequate. And it is not as if the aid being

given is substantial. The Php98.5 billion distributed to 17.45 million

household for the first tranche averages to Php5,645 per family. This amounts

to just Php43 daily per family when spread over the 130 days since the lockdown

was imposed. Those receiving a second tranche may double this but, still, Php86

is a paltry amount to stretch over four months of having no, low, or unstable

incomes. Expenses for food, rent, utilities and even debt continued or, at

best, were only momentarily delayed by the lockdowns.

Too many families will not get the “Php5,000-8,000” monthly

promised. This is because the actual cash subsidies disbursed per household

depends on the minimum wage of the region where the beneficiary resides, as per

the DSWD’s Joint Memorandum Circular No. 2 Series of 2020 (JMC No. 2-2020). The

maximum subsidy per family is: Php5,000 in Regions 5, 8, 9, 12, CARAGA and

ARMM; Php5,500 in CAR and Regions 1 and 2; Php6,000 in Regions 6, 7, 10 and 11;

and Php6,500 in Regions 3 and 4A. The Php8,000 maximum subsidy is only given in

the NCR.

Moreover, those already receiving 4Ps, DOLE and DA assistance will

have these equivalent amounts deducted from the maximum regional subsidy. As it

turns out, the DSWD does not necessarily give the emergency cash subsidy in its

entirety and in many cases just tops up existing amounts received from other

programs.

The biggest subsidy is supposedly in NCR. Even assuming that

households here all get their second tranche by end July, their cash aid only

amounts to Php118 per family if spread across 136 days (March 16-July 30). This

may buy a family of five a kilo of rice and viand for a day but does not leave

much for any other essential needs.

Social welfare advocates say there should even be a third and

fourth tranche especially because the lockdown extended beyond the two months

stipulated in the Bayanihan law. Unfortunately, even as the lockdowns were just

starting, the Duterte administration already insisted that it was running low

on funds and that not everyone can get “ayuda”.

Chaotic. The SAP is not just limited and stingy by design – it has also

been implemented poorly. Distribution of the first tranche was marred with

controversy and reportedly even corruption. This includes authorities dividing

a single pay-out into several parts for different households, beneficiaries

receiving very small amounts or receiving the maximum subsidy twice, and

low-income households not receiving aid at all while better-off households do.

Other irregularities include ineligible beneficiaries in GCQ areas

still receiving a second tranche, wait-listed beneficiaries already lined up to

get a second tranche, and confusing monitoring of the second tranche and the

wait-listed beneficiaries.

The DSWD also explains delays in proceeding with pay-outs as due

to its “de-duplicating” and certifying all the other non-4Ps names submitted by

the local government units (LGUs). This process will cover the original 17.7

million beneficiaries as well as the additional five million wait-listed

beneficiaries. It says that 81,000 duplications have so far been discovered.

All these bureaucratic inefficiencies are delaying completion of

the first and second tranche payouts, and government’s lack of will to resolve

them is just making the public suffer even more.

Falling short. The administration boasts of

giving SAP to millions of families, but it is silent on how millions affected

by the pandemic lockdown are still left behind.

IBON estimates some 15.9 million formal and informal workers

displaced by the lockdown. Yet DOLE’s COVID-19 Adjustment Measures Program

(CAMP) and Tulong Panghanapbuhay sa Ating Disadvantaged/Displaced Workers

(TUPAD) beneficiaries numbered only 557,924.

The livelihoods of around 9.7 million farmers and fisherfolk were

also disrupted, but only 1.2 million were targeted as beneficiaries of DA’s

Rice Farmers Financial Assistance (RFFA) and Financial Subsidy to Rice Farmers

(FSRF) programs.

The 10.6 million families who were in ECQ/MECQ areas won’t be

getting their promised second tranche because this took so long in coming and

the aid was not given out before lockdown restrictions were relaxed. They are

expected to now fend for themselves even as livelihoods remain unstable and

millions are still without jobs.

Transform SAP. All these SAP troubles are preventing

much-needed help from reaching all of the poorest Filipinos grappling with the

COVID-19 crisis. It is far behind schedule, grossly insufficient, and leaves

behind millions who are still reeling from joblessness and falling incomes. Yet

it is very much possible to give sufficient aid swiftly and efficiently.

The Philippines can draw lessons from cash transfer systems in

Vietnam and Fiji during disasters. When tropical Cyclone Winston hit Fiji in

2015, the government gave its unconditional cash voucher assistance (CVA) to

needy coastal citizens’ mainly through their mobile phones. The United Nations

Office for Disaster Risk Reduction said Fiji “was able to reduce the impact of

the disaster on the poorest by more than 20 percent”. When Typhoon Ketsana struck

Vietnam in 2015, the government, humanitarian organizations and affected

communities worked closely together to ensure timely and transparent delivery

of financial assistance.

There are also positive local practices to build on closer to

home. Some NCR LGUs ensured funding to provide financial assistance to all

households under their jurisdiction. Better-off families waived their share in

the spirit of ensuring that there would be enough for those in need. Other LGUs

used their pre-COVID database of constituents and channeled cash transfers

unconditionally to each adult resident through financial service providers

(FSP).

The SAP difficulties highlight the limitations of the country’s social protection systems, not just during disasters but in the course of daily underdevelopment. A genuinely compassionate government would not just fix the system of SAP to ensure expedient socioeconomic relief alongside boosting public health capacity as the people’s supposed shield against the pandemic.

A genuinely compassionate government would also fix the Philippine economy to be ready when the next pandemics and crises strike. This means building strong local agricultural and industrial sectors providing stable jobs and incomes and also the facilities and infrastructure for meeting the people’s and the nation’s basic essential and development needs.