State of abandonment, state of terror

Looking at history, one can say that state abandonment is very much the official disposition on which the labor export system is hinged. The Philippine government is fundamentally inclined to function simply as what sociologist Robyn Rodriguez calls a “labor brokerage state,” an institutional apparatus that facilitates Filipinos’ outward labor traffic.

By LAURENCE MARVIN CASTILLO

Bulatlat.com

MELBOURNE, Australia – In mid-June 2020, a Filipino supporter of President Rodrigo Duterte who is based in Melbourne, Australia appeared in an online broadcast of Rekta Aksyon, a “public service” program hosted by the Philippine National Police bureau in Central Luzon. This supporter claimed that progressive Filipino organizations in Australia like Migrante, Anakbayan and Gabriela solicit donations from Australians to buy weapons for the armed revolutionary group New People’s Army.

There is nothing new to the accusation; similar broadcasts that feature interviews with Duterte supporters overseas are uploaded on Rekta Aksyon’s Facebook page, seeking to discourage membership in, or support for, progressive mass organizations. It is easy to suspect that Filipino taxpayers’ money is being used to fund these smear campaigns; in the broadcast that featured the Melbourne-based guest, it was mentioned that the government has set up a program to support Filipino “frontliners” (read: Duterte supporters) through the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict. Formed as the command center of Duterte’s counterinsurgent machinery, the task force has been allotted millions of pesos, part of which some of its officials have reportedly spent on lavish junkets abroad, hoping to discourage “funders” of groups accused of being communist fronts. With the governments’ push to implement the recently-signed terror law, the agency has become more aggressive in its disinformation campaign of tagging progressive organizations and individuals as communist fronts and terrorist supporters.

The overseas reach of counterinsurgency propaganda reveals something about the Philippine government’s paranoia over the growing discontent felt by migrant Filipinos, especially in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. From the time it was elected in 2016 until the current global crisis, the Duterte administration has actively sought migrant Filipinos’ support and approval — and there is a perception that it has been successful in this undertaking. This perception can be explained by a number of factors, one of which relates to the role of social media in influencing how OFWs form their opinions about politics in the home country. Crucial to this social media landscape is the proliferation of regime-supportive and possibly regime-sponsored fake news pages and trolls that disseminate fascist articulations and imaginaries to concoct a fiction of national economic and political stability, even when such fiction is belied by the very conditions compelling Filipinos to turn to overseas work. Indeed, one can read Duterte’s appointment of Mocha Uson, pro-Duterte social media influencer and former Communications assistant secretary, to the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration as a gesture of further linking OFWs to the regime’s disinformation strategies.

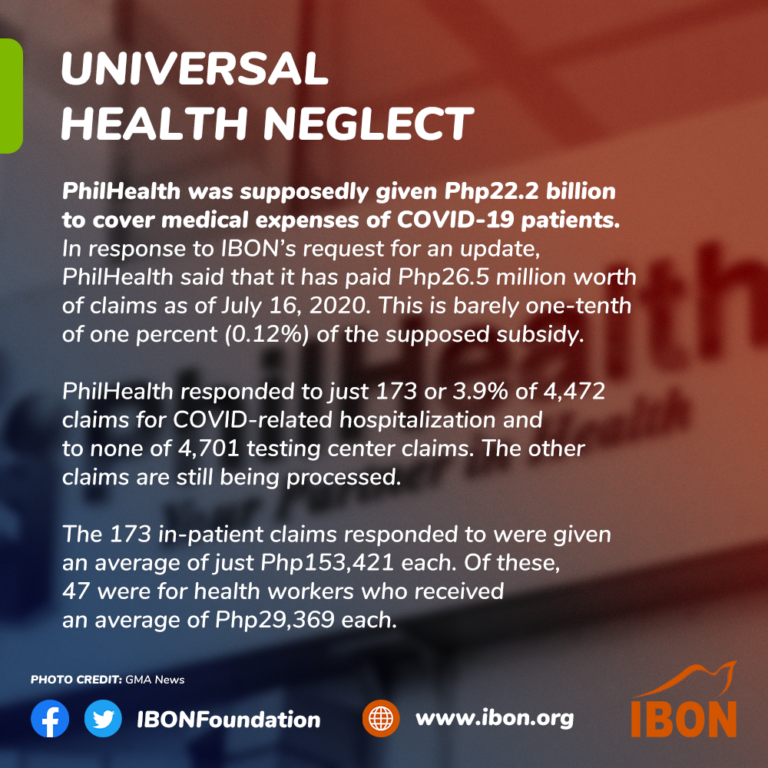

Upon the onslaught of the Covid-19 pandemic and the various crises attendant to it, the Philippine state’s instrumentalist relationship to the country’s migrant workers has become even more visible. Filipino migrant workers and international students were further thrust to the economic margins of their host countries, either fired or stood down by their employers. The Philippine state, however, has done very little to look after disenfranchised migrants. Embassies and consulates have failed to mobilize comprehensive welfare drives especially for Filipinos left with little to no means to survive. Worse, in May, an additional burden to the already weary overseas population was imposed, in the form of a circular directing an increase in mandatory payments to PhilHealth, the government’s health insurance corporation.

The pandemic has left thousands of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) with no choice but to go back to the Philippines. Compounding the sense of economic uncertainty that confronts them upon returning home is the subhuman condition to which they are being subjected. There are reports of returning migrants confined in unkempt, barely habitable quarantine areas, of migrants forced to camp out under a flyover near the international airport, and even of migrants pushed to the brink by desperation, choosing to end their lives.

Looking at history, one can say that state abandonment is very much the official disposition on which the labor export system is hinged. The Philippine government is fundamentally inclined to function simply as what sociologist Robyn Rodriguez calls a “labor brokerage state,” an institutional apparatus that facilitates Filipinos’ outward labor traffic. The state’s social responsibility for OFWs practically ends in the airport gates, as the transaction between the Philippine state and the host country is largely a profit-oriented one, in which questions of social protection, decent work, fair pay and labor rights barely figure. For OFWs, navigating the overseas labor market means relying on one’s individual will and capacity to survive. In the worst of circumstances, when they are forced to turn to overseas state agencies, they only end up confirming the Philippine state’s inadequacy in securing their welfare.

It is even more insidious that when the Philippine state chooses to extend its political reach amidst and among OFWs, it is to flex its counterinsurgent capacities by restraining dissent overseas. A prominent example is the stymied attempt, in late April, to deport a Taiwan-based OFW who aired her criticisms of the government online. Then, of course, there is the covert sponsorship of smear campaigns against legal migrant organizations. What is ironic is that in the face of state neglect, these organizations are among the groups that step up to address migrant concerns and fill in the gaps left by state abandonment. These groups inspire possibilities of nation-based identification that refuses the individualizing survivor mentality that such abandonment often gives shape to. This identification – premised on solidarity and given to justified collective outrage over government crimes of omission and commission – is always and understandably opposed by a state that is increasingly dependent on fabricating national political fictions that now fail to convince day by day.

The author is a PhD student at the University of Melbourne. He is currently working with Filipino migrant organizations like Migrante, Anakbayan and Philippine Studies Network in Australia.

*This essay is part of Everyday Emergencies, a joint project of Ibong Adorno and Institute for Nationalist Studies, containing state-of-the-nation articles written to expose, analyze, and document the Duterte administration’s leadership amid the COVID-19 Pandemic.

The post State of abandonment, state of terror appeared first on Bulatlat.

Duterte’s COVID-19 response, no sense of urgency

With the cases increasing, concerned government agencies are swamped with backlogs, particularly on validating COVID-19 cases and an overwhelmed public health system.

By JANESS ANN J. ELLAO

Bulatlat.com

MANILA – President Rodrigo Duterte is set to deliver his fifth State of the Nation Address on Monday. But where does the country stand now with the raging pandemic and a failing fragmented public health care? .

Duterte’s recent statement — that COVID-19 is “perhaps” the country’s number one problem – sums up his administration’s response to the pandemic, without urgency.

For four months now, the Philippine government has gone from claiming it is prepared to tackle the spread of the COVID-19 virus head on to putting the blame on its own people for supposedly being hard-headed on heeding health advisories. The country has the longest and strictest lockdown and yet sustained community transmission remains.

The Philippines has one of the leading number of active cases and the least number of recoveries in the whole of Southeast Asia. The number of cases, regardless whether it is considered as “fresh” or “late,” also has yet to be flattened, with the cumulative cases now at an almost 78,000-mark.

Yet, Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque said the Philippine government is “winning” against the spread of COVID-19 and that recent spike in the number of new cases these days are not alarming.

But with over 1,000 cases a day, the government’s data reveal that the country is far from flattening the curve, particularly in Metro Manila and Central Visayas, where its intensive care has gone to dangerous levels in recent days.

In May, the World Health Organization said a comprehensive strategy will require case identification, isolation, testing and care, and contact tracing and quarantine. This, they said, are critical activities “to reduce transmission and control the epidemic.”

But where do we stand now?

No mass testing

The Philippine government has not undertaken mass testing, which health advocates have long been pushing for, particularly for frontliners, returning overseas workers, and the vulnerable sectors.

As of now, there are 86 approved testing centers, per the health department report on July 23.

In May, health secretary Francisco Duque III said the government plans to have a testing capacity of 30,000 a day by early June. However, COVID19stats.ph said an average of 26,183 tests have been conducted for the past seven days last July 23.

With the cases increasing, concerned government agencies are swamped with backlogs, particularly on validating COVID-19 cases and an overwhelmed public health system.

Independent thinktank Ibon Foundation said the current healthcare system is operating close to its maximum capacity while the Philippine government remains to have “no clear and concrete plan to expand testing triage and capacity.”

As of July 29, the COVID19Stats.ph said there are over 5,185 samples in the backlog, awaiting for processing. It also noted that there are 94,919 individuals who tested positive, adding that the number is bigger than what is reported as cases need to undergo case validation and processing.

The delay, according to Jillian Francise Lee, provincial health officer of the Province of Dinagat Islands, in a webinar hosted by Cure Covid, is often a result of the absence of a unified data collection of the health department. On the ground, health workers write their reports by hand, which are then transmitted to the regional office for encoding.

The process of getting test results, she added, is a different story.

In a webinar hosted by the Coalition of People’s Right to Health, University of San Augustin’s Supervising Science Research Specialist Pia Zamora said the process of sample collection, sending to laboratory, to validation range from three to five days for the provinces of Western Visayas.

“Not only are we ‘low tech.’ We also lack human resources and the data are politicized. Instead of transparency, we get it with political layers and are provided with terms that people find confusing,” Reginald Pamugas, a community-based psychiatrist, said in the same webinar.

Contract tracing is as bad.

Apart from mass testing, contract tracing is also proving to be a challenge for the Philippine government. Among the most recent proposals include the police going house-to-house in search for COVID-19 positive and hiring of gossip-mongers in the community.

It is also not clear how fast they were able to conduct the contact tracing especially since “real time reporting is needed so contingency measures can be done.”

In Western Visayas, for example, of the 104 confirmed cases as of May 18, 2020, Zamora said contact tracing yielded 3,503 individuals but only 3,420 were identified and 1,668 tested. This, she said, shows there is delink between the number of persons identified during contact tracing and those tested by nearly 50 percent.

As of July 23, the health department said 52 percent of health facilities have been occupied. In the National Capital Region, bed occupancy for COVID-19 related cases is considered on danger zone, with 76 percent bed occupancy.

The Philippine General Hospital, one of the two dedicated COVID-19 hospitals in Metro Manila, said it has now reached its full capacity status.

At least seven mega-facilities were transformed to quarantine areas. Among these include: Ninoy Aquino Stadium in Manila; PICC Forum in Pasay City; Rizal Memorial Coliseum in Manila; World Trade Center in Pasay City; ASEAN Convention Center, Clark, Pampanga; National Government Administrative Center, New Clark City, Capas, Tarlac and Philippine Sports Complex, Pasig City.

However, conditions in these quarantine facilities are, to say the least, far from ideal. Overseas Filipino workers who underwent mandatory quarantine lamented that they were cramped in rooms, making physical distancing impossible.

In fact, COVID-19 spread among OFWs who stayed in government quarantine facilities. Migrante International said this is due to the unsuccessful polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, violation of one-person-per-room policy, no widespread provision of face masks and alcohol, lack of systematic health monitoring and violations of social distancing measures.

In May, Migrante revealed that nearly 400 OFWs were brought to the World Trade Center (WTC) and 10 of them tested positive for COVID-19. Only 15 of them had an early swab testing due to symptoms and the rest were tested the following week. Eight out of 15 came out positive.

Seafarers who were brought to New Clark City, meanwhile, also complained of absence of mass testing and medical assistance. In a report published on May 30, OFWs who were housed in Parañaque and Pasay, had been waiting for two months for the results of their swab test. Four OFWs were assigned in one room; some of them were sleeping on the floor.

Health workers as victims

Bearing the brunt of failed government response are health workers serving in the frontlines in various hospitals. Personal protective equipment remain lacking for most, forcing them to be creative in protecting themselves against the virus.

Last week, health workers at San Lazaro Hospital, the country’s primary infections hospital, held a protest action as they decried the growing number of workers among their ranks who have been afflicted by the virus.

Ulysses Arcilla, a nurse and president of their employees association, said the hospital still lacks personal protective equipment and non-implementation of regular testing. They too are subjected to long working hours due to staff shortage.

With about 80 health workers who have been afflicted by the dreaded virus, Arcilla said it hurts to think that they too have become patients. It is more saddening, he added, that there would be no one to take care of them if everyone becomes sick.

Poor suffer the most

Apart from health workers, ordinary citizens – both patients or not – are also shouldering the brunt of the poor government response on COVID-19.

Kadamay said urban poor dwellers have been consistently left out of social assistance packages by the government. The snail-paced process that they need to endure, the group added, has left the poor hungry.

Access to COVID-19 testing proves to be a challenge for the poor and disadvantaged, with tests amounting from a little above a thousand pesos to as much as P15,000.

As a result, local governments and health workers on the ground, doctor Leonardo Javier said, continue to shoulder the shortcomings of the national government in leading the country out of this pandemic.

“Where have the trillions of debt for COVID response gone to?” he asked in Filipino.

Apart from the increasing cost of testing and hospital care, Javier said patients also experience stigmatization by the Philippine government, adding that they are being treated like criminals.

“Communities are facing a grim situation now,” Javier said, with about seven to eight Filipinos dying without getting due medical treatment before the pandemic.

The COVID-19 has exposed the ineptitude, insensitivity and criminal neglect of the Duterte administration.

The post Duterte’s COVID-19 response, no sense of urgency appeared first on Bulatlat.

Davao activists will take to the streets on Duterte’s SONA

Progressive groups here will go back to the streets since the start of the Covid-19 quarantine in time with President Duterte’s fifth State of the Nation Address (SONA) this Monday, July 27, 2020.