May 3, 2022, Reuters

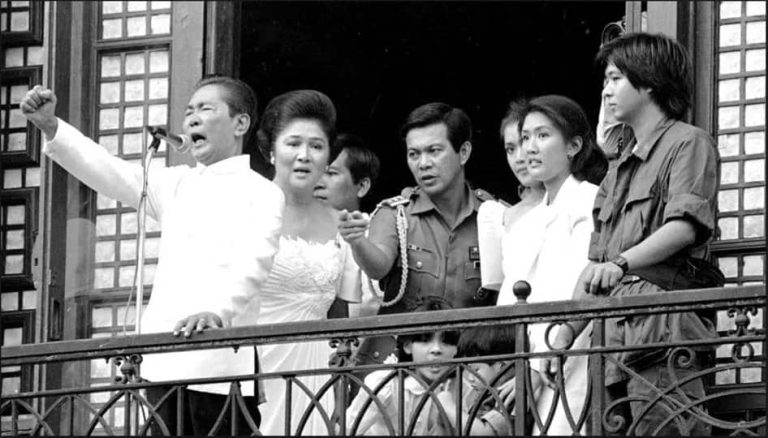

A special report by Reuters says a victory by the son and namesake of the dictator represents an extraordinary resurrection for his family, coming 36 years after his father was toppled in a popular uprising and fled Manila by helicopter with the family

MANILA, Philippines – If Ferdinand Marcos Jr. triumphs in the upcoming Philippines presidential election, he will wield broad powers over government agencies seeking to recover as much as $10 billion plundered by his namesake father during his autocratic rule.

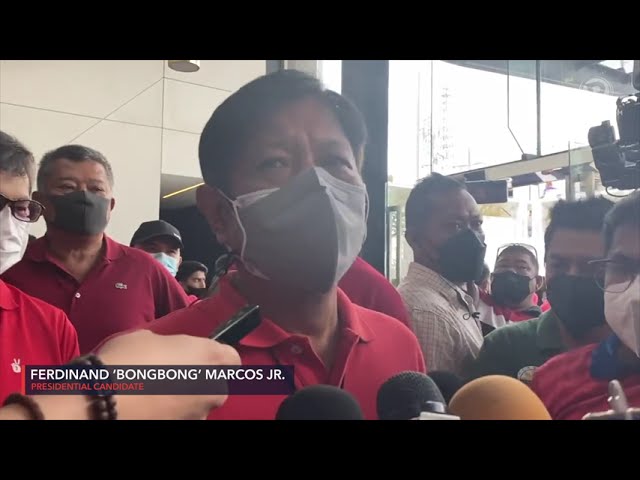

Marcos is on course to win the May 9 election, according to opinion polls. A survey taken in mid-April put him 33 percentage points ahead of his nearest rival, propelled by strategic political alliances and a well-funded campaign.

A victory for the 64-year-old Marcos, known in the Philippines as Bongbong, would represent an extraordinary resurrection for his family, coming 36 years after his father was toppled in a popular uprising and fled Manila by helicopter with the family.

Marcos and his family have often said that their vast fortune was legitimately obtained. On the campaign trail he has dismissed criticism about how the family obtained its wealth as “fake news.” Asked in an interview in January about the government’s efforts to recover the plundered assets, he said the family was “no longer involved in the cases,” adding that “what the court orders, we will follow.”

But a Reuters review of court filings, government documents and legal depositions by the presidential candidate, along with interviews with former investigators and lawyers, underscore the role Marcos has played in protecting the family’s wealth and thwarting efforts to retrieve it. Marcos and his family have defied court orders and appealed rulings requiring them to surrender assets. They are still defendants in at least 40 civil cases related to their wealth. In addition, Marcos’ 92-year-old mother, Imelda Marcos, is appealing her criminal conviction on seven separate graft charges in 2018, each of which carries a maximum prison sentence of 11 years.

As president, Marcos would hold sway over the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG), which is devoted to investigating and recovering the Marcos family’s wealth. The president has the authority to appoint the commissioners of the PCGG. A former commissioner told Reuters the president can also assign the agency tasks.

The president also appoints the Ombudsman, who oversees graft and corruption complaints against the government, as well as the head of the tax office. The Marcos family has for years refused to pay a tax bill that local media reports say now amounts to $3.9 billion, including penalties. Most recently, the Bureau of Internal Revenue sent a letter of demand in December to “the Marcos heirs” regarding the unpaid taxes.

Marcos has already intimated what he might do with these presidential powers. “You could say that the first time it was organized, it was really an anti-Marcos agency,” he told local DZRJ Radio in March, referring to the PCGG. “Nonetheless, we could turn it into a real anti-corruption agency.”

Marcos and his mother Imelda did not respond to questions for this story.

The PCGG, which was set up in 1986, has retrieved about $5 billion of the Marcos fortune, PCGG chairman John A. Agbayani told Reuters last week. But another $2.4 billion is still caught up in litigation, he said. Still more remains missing, former government investigators say. Citing US intelligence estimates, the first head of the PCGG, Jovito Salonga, said back in the 1980s that the family’s wealth “ranged from 5 to 10 billion dollars and even beyond that.”

Ruben Carranza, a former PCGG commissioner, believes that a Marcos victory will usher in a new phase in the 36-year battle to retrieve the family’s assets. Carranza told Reuters he is concerned Marcos will use the PCGG to ensure the family holds onto “whatever ill-gotten wealth they have kept.”

PCGG chief Agbayani said he believed whoever is elected president would “not interfere” in the litigation of pending court cases. “Even under a Bongbong Marcos presidency, I am confident that he will respect the rule of law, and the doctrine of Separation of Powers of the Executive and the Judiciary,” he said in a statement.

Agbayani said the powers of the PCGG should be expanded beyond its current focus on the Marcos family to include recovering “ill-gotten wealth of high government officials.”

Crates of cash

The hunt for the family’s riches began just hours after the Marcoses fled the Philippines as millions took to the streets in February 1986 amid widespread concerns Marcos Sr. had rigged the presidential election. The family went into exile in Hawaii.

They didn’t leave empty-handed, taking with them a stash of gold, jewelry worth $4 million and 22 crates of cash, according to US Customs, which seized the assets.

In their haste, the family left another cache of jewelry, artworks and designer clothes in the presidential palace and with associates. This included at least 1,200 pairs of shoes, part of Imelda Marcos’ huge collection of luxury footwear.

Crucially for investigators, the Marcoses left many documents in safes and filing cabinets at the palace.

The new government of Corazon Aquino, who replaced Marcos as president, set up the PCGG three days after the end of Marcos’ two-decade rule with its first executive order. Soon after, the agency announced it had obtained evidence of Swiss bank accounts controlled by Marcos Sr. and Imelda, kick-back schemes and monthly “donations” to the dictator from wealthy businessmen who had benefited from government policies.

The seized documents, as well as affidavits by a key financial adviser to the Marcoses and business associates, revealed a globe-spanning treasure: a network of bank deposits, trust accounts and foundations scattered around the world; a vast real estate portfolio, including four buildings in Manhattan; and a collection of more than 150 paintings, including works by masters such as Michelangelo, Van Gogh and Picasso, many of which are still missing.

The documents, affidavits and further investigations also revealed the family’s silent ownership of some of the largest companies run by business associates, popularly known in the Philippines as “cronies.” The World Bank said in a 2007 report the family’s “ill-gotten wealth” was also accumulated via the “raiding” of the national treasury and “skimming off foreign aid.”

“The greed was simply unparalleled, the plunder unmitigated, the pattern unbelievably remorseless,” the PCGG said in a 2016 submission to the Supreme Court in another case involving the family’s wealth. “All these in the face of the Filipino people’s continuing misery and suffering!”

Following the death of his father in 1989, Marcos became deeply enmeshed in litigation in the Philippines and United States as co-administrator of the estate. He said at the time he had little knowledge of the family’s wealth, including in two previously unreported depositions in 1991 and 1993 given under oath for a US court case, which Reuters reviewed. Asked in 1993 if his father involved him “at all” in the management of the family assets between 1980 and 1986, the last years of his presidency, Marcos replied: “I don’t know what the family assets are. No. I wasn’t involved in any of that.”

Marcos’ deposition was at odds with testimony he gave in 2007 in a case where the Philippines government was trying to seize assets connected to the family from billionaire Lucio Tan, whose sprawling conglomerate touched many facets of the economy.

Tan was one of the dictator’s close business associates and paid kickbacks to him, according to the PCGG. Asked in an article published in the Los Angeles Times in 1987 if documents showing he paid $11 million to Marcos Sr. were accurate, Tan answered, “Add one zero, maybe two.”

In a transcript of Marcos’ testimony in the 2007 case, reviewed by Reuters, he recalls being called into his father’s office before they were exiled to Hawaii in 1986 and shown “Shares of Stock” and property titles. “He at that point told me that he would like me to familiarize myself with the operations of some of the enterprises that we have interests in and that Mr. Lucio Tan was going to help me,” Marcos told the court.

During several meetings, Tan “laid out the ownership structure” of corporations the family had a stake in, Marcos said. According to the transcript, Marcos then reeled off some of the names of these businesses and described in detail how some of the companies were structured.

It was part of a larger effort to do an inventory “of all those business interests that we have,” Marcos told the court. “My sister Imee, who has legal training, was given the job of conducting the legal audit, and I was given the job to go to as many of these enterprises as I could.”

Tan and Imee Marcos did not respond to questions from Reuters.

During his father’s reign, Marcos studied at Oxford University in the 1970s, where he received a “special diploma” in social studies but didn’t complete a full degree, the university said. He also studied for an MBA at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in the United States between 1979 and 1981, but did not complete the course, he said.

In 1991, two years after Marcos Sr. died, Imelda and her children were allowed to return to the Philippines. Imelda herself has since faced multiple criminal charges, while the family has been involved in scores of civil suits seeking to recover their riches.

Imelda, who lives in Manila, has only been convicted in the 2018 graft case. The court ruled that the case involved the transfer of more than $300 million of “ill-gotten wealth” to overseas bank accounts while she was Minister of Human Settlements, a position she held during her husband’s presidency. PCGG chairman Agbayani said Marcos had been acquitted in three earlier criminal cases and that there were other criminal cases still pending.

After returning, Imelda twice ran unsuccessfully for president and was elected to Congress for four terms. Her son has also spent most of his time in politics since returning, including two stints in the House of Representatives, interspersed with a terms governor of the family’s stronghold in the province of Ilocos Norte. Marcos also served as governor and vice governor of the province during his father’s rule. He was elected to the Senate in 2010 before unsuccessfully running for vice president in 2016, losing to Leni Robredo.

Robredo, a human rights lawyer, is now Marcos’ main rival in the presidential race and has targeted the family’s wealth during the campaign. “If the son benefits from the father’s sin, he is also guilty,” she said in February. “If you are benefiting from the very act for which your father was being judged, you should also be judged.”

The family negotiated two deals with the Philippines government in 1992 and 1993 that would have allowed them to keep part of their wealth, court records show. According to the later deal, they would have kept 25% of $356 million found in Swiss bank deposits. But the deals were never authorized by the presidents at the time and were declared null and void by the courts.

The courts have also repeatedly rejected the Marcos family’s assertion that their wealth was legitimately obtained.

Based on the tax filings of the dictator and his wife, the Philippines government has said that the Marcoses earned the equivalent of $304,372.43 in “known lawful income” during Ferdinand Marcos’ presidency. The Supreme Court accepted that calculation in a 2012 ruling that rejected a petition from Marcos and his mother to keep $40 million in a Merrill Lynch bank account claimed by the Philippines government. The assertion by Marcos and his mother that the late president’s legitimate income was far higher was “a sham and evidently calibrated to compound and confuse the issues,” the court said.

Mythical gold

In interviews over the decades, Marcos and his mother have referred to a huge haul of gold belonging to the dictator to explain their wealth. Marcos has said that his father built his wealth from trading in precious metals before he became president in 1965, according to Rappler, a local media outlet.

In interviews, Imelda Marcos has said her husband had six to seven tons of gold when he entered politics.

In a 2015 interview with local media, Marcos said his father discovered the so-called Yamashita treasure – a mythical cache of bullion supposedly left by Japanese troops retreating from the Philippines in 1945.

Asked about the gold in a March interview on the local One News channel, Marcos changed tack. “It does not exist,” he said.

Even so, the explanation of a gold haul underpinning the family wealth has gained currency on social media. One outlandish theory posits that the descendants of the Tallano dynasty that once ruled much of the Philippines gave Marcos Sr. and a Catholic priest a 30% share of 640,000 ton of gold that the pair helped them recover from the Vatican and return to the Philippines after World War Two. The theory has been promoted on social media by the political party originally founded by the dictator and which is now supporting Marcos Jr. The World Gold Council says only around 205,000 tons of gold has been mined throughout history.

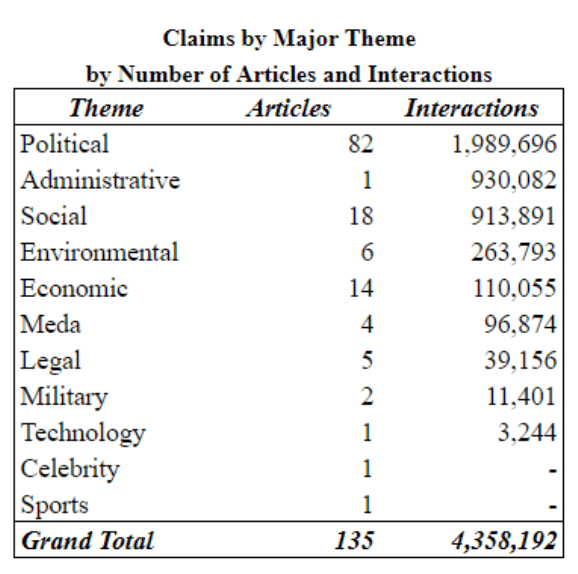

The VERA Files, an independent Philippines fact-checking organization that has a contract with Facebook, said disinformation about Marcos and his family’s wealth surged last year. Several posts on Facebook and Youtube proclaimed that the family will give a large share of its wealth to the public if Marcos wins office. One of the main drivers of the social media traffic was a Facebook group called “Bongbong Marcos for Progress, Peace and Prosperity 2022,” according to the VERA Files.

In a statement, a spokesman for Facebook-owner Meta, Kevin McAlister, said the group had “repeatedly shared content that our fact-checking partners have debunked, which means it can’t monetize or advertise and we move all its posts lower in Feed so fewer people see them.” A warning label had been added to “several posts from this group,” he said.

Ruel Andayo, 44, a coconut seller in Manila, told Reuters he was voting for Marcos because of the “promise” that the family’s wealth would be shared with the people. Asked where he got the information, he replied: “Someone just said.”

“Bongbong’s wealth was not stolen. It was just an attempt by the yellows to ruin him,” Andayo added. He was referring to the yellow color associated with the “People Power” protesters who ousted Marcos in 1986.

On the campaign trail, Marcos has appeared at mass rallies with Sara Duterte-Carpio, the daughter of outgoing President Rodrigo Duterte and his running mate for vice president. At a rally in the city of Lipa south of Manila in April, the crowd was treated to fireworks and performances by local pop stars.

Marcos’ son, Ferdinand Alexander Marcos, popularly known as Sandro, is also playing a role. He is running for Congress and has featured heavily in the campaign, especially online, where his posts have drawn adoring responses from young women.

Political analysts say a decades-long public relations effort to alter perceptions about his father’s presidency, much of it disseminated via social media, has benefited Marcos. But key to his frontrunner status, they add, is his partnership with Duterte-Carpio.

Ronald Holmes, president of Pulse Asia, a Manila-based polling firm, told Reuters that Marcos’ support doubled after he partnered in November with Duterte-Carpio. The move garnered him mass support from the Duterte stronghold in the southern island of Mindanao and big cities like Cebu where he had previously languished. In the multi-ethnic Philippines, “many voters pick candidates on ethnic-linguistic lines,” Holmes said.

Never ‘repentant’

While Marcos has said the family is not a party to any ongoing court cases, PCGG chairman Agbayani told Reuters that in “all pending civil cases for recovery” of the wealth, Marcos and his sister Imee “substituted their deceased father as heirs in a representative capacity, pursuant to our rules of court.”

Antonio Carpio, a former Supreme Court justice, told Reuters the Marcos family has opposed “every move” of the Philippines government to recover its wealth, including lodging frequent appeals of court decisions.

“They have never been repentant,” said Carpio. “They have never acknowledged these (assets) are ill-gotten wealth.”

Marcos has been personally involved in some of the appeals. In January 2020, he filed a motion to the Supreme Court supporting the objection by his mother and his sister Irene to a ruling that rejected the family’s ownership of more than 150 artworks, including the missing masterpieces. The case, which is listed as still pending by the PCGG, has been litigated for 31 years.

Irene Marcos did not respond to questions from Reuters.

In the United States, the family has used similar tactics to thwart legal action against them. One such case involves a class action heard by the US District Court in Hawaii seeking redress for victims of martial law, a period that extended for almost half of Marcos Sr.’s presidency. During this time, some 70,000 people were imprisoned, 34,000 were tortured and over 3,200 were killed, according to Amnesty International.

The case was launched two months after the Marcos family went into exile in Hawaii. In 1995, the district court awarded almost $2 billion to 9,539 victims. The Marcoses lodged at least three unsuccessful appeals before a final contempt order and an additional $353 million penalty were imposed on Marcos and his mother by the court in 2011 – a ruling they also appealed.

Still, only about $37 million of the $2 billion award has been recovered from the sales proceeds of artworks and property owned by the family in the United States, said Philadelphia-based lawyer Robert Swift, who launched the class action.

Mila Sibayan, 63, is one of the plaintiffs. She was arrested in 1983 and detained for three years in a military base for helping lead a petition opposing a pulp mill owned by a golfing partner of the dictator. Sibayan says she was sexually molested by a soldier and held in painful stress positions during interrogations. In one instance, she was jammed into a metal drum with another woman and rolled around the military base.

Sibayan said her husband, who was an activist and also one of the plaintiffs, was beaten with a wooden plank and a rifle butt. He passed away in September.

Sibayan said she and her husband filed an affidavit about their detention, but no longer had a copy. They received a total of about P180,000 in 2010 and 2014 (about $3,400 today). At the time, they were a working couple with two children living on a combined income of $95 per month.

“You can never put a price on the kind of suffering we endured,” Sibayan said.

The president, who serves a single six-year term, also chooses the heads of other government bodies that could play a role in recovering the family’s wealth. The central bank governor, who is chosen by the president, doubles as the head of the country’s anti-money laundering council, according to the council’s website. The president also selects the head of the nation’s anti-corruption commission.

Marcos has questioned whether there were widespread human rights abuses during his father’s rule. As president, he would also appoint the chairman of the human rights commission.

When it comes to the judicial system, the president has extensive powers. As well as appointing prosecutors and the solicitor general, who represents the government in court, the president also appoints judges.

Agbayani said he believed the PCGG should complete its work on “the Marcos ill-gotten wealth” in seven years. “This means that all litigation is terminated by that time,” he said. “All recovered assets are sold/privatized by that time.”

Antonio La Vina, professor of law and politics at the Ateneo de Manila University, is concerned this won’t happen. If Marcos wins, he said, then prosecutors and the PCGG will not pursue the pending court cases involving the family’s wealth for his entire presidential term.

“For six years, cases will not move,” La Vina told Reuters, “so they will die a natural death.” – Rappler.com