“Pieces of gold, the size of walnuts and eggs, are found by sifting the earth in the island of that king who came to our ships,” chronicled the explorer, Antonio Pigafetta, about Raja Siagu upon the Spaniards’ arrival in Butuan during the Magellan expedition. “All the dishes of that king are of gold and also some portions of his house as we were told by that king himself. He had a covering of silk on his head, and wore two large golden earrings fastened in his ears … At his side hung a dagger, the haft of which was somewhat long and all of gold, and its scabbard of carved wood. He had three spots of gold on every tooth, and his teeth appeared as if bound with gold.”

One can only imagine the awe that overcame these European explorers when they discovered such a rich and elaborate society. Even today the Philippines possesses one of the world’s largest gold deposits, and there is evidence that mining began as early as 1000 BC. By the time the Spanish conquistadors reached Philippine shores, the islands had a flourishing culture that traded in the precious metal and citizens adorned themselves in gold to display status.

It was in 1975, during an extensive construction project, that the Butuan archaeological site was discovered. During the excavation that followed, an enormous wealth of artefacts was unearthed: from high fired ceramics from China and Southeast Asia and Persian glassware, to impressive open water boats called balanghals, and one of the most significant findings of pre-colonial gold. “From excavations in Butuan in the 1970s and the irregular gold recoveries from the 1960s to the 1980s, as well as written Chinese sources from the Song Dynasty, Butuan appears to have been a thriving polity with a hierarchical social structure, and engaged in trade with neighbouring Southeast Asian cultures and China,” shares the curator of Ayala Museum’s Gold Exhibit, Florina H Capistrano-Baker, about the forgotten kingdom.

On another construction site in 1981, heavy machinery operator Berto Morales discovered approximately 22 pounds of gold pieces, now known as the Surigao Treasure. Some of these valuables showcased to rave reviews, intriguing an international audience at The Asia Society in New York in 2015, an exhibit also co-curated by Baker. “We as a people are always searching for our identity, but when you see this collection you think ‘Oh my goodness, that is the core! That is who we are!’”

For a country whose pre-colonial ancestry has left meagre evidence—no grand monuments or architectural structures and very few original manuscripts— these beautifully crafted solid gold pieces are a direct link to our heritage. “The pre-colonial gold bears witness to an advanced society with cultural ties to other, better-known cultures in Southeast Asia such as Java. It demonstrates that we had the technical skills and resources to produce these wonderful objects. It also suggests familiarity with Hindu-Buddhist ideas that have largely been erased from our cultural memory.”

Seasoned collector, Jomari Treñas, is fascinated by this intermingling of societies and how they are clearly translated in the designs. “You see the different cultures in the gold-making, such as the gold heads or earrings with figures that have very Indian influences. This one pair that I have is an interesting specimen: shaped like a Garuda, a mythological bird derived from Hindu and Buddhist beliefs, it shows clear evidence of cross-cultural exchanges even before the colonial period.”

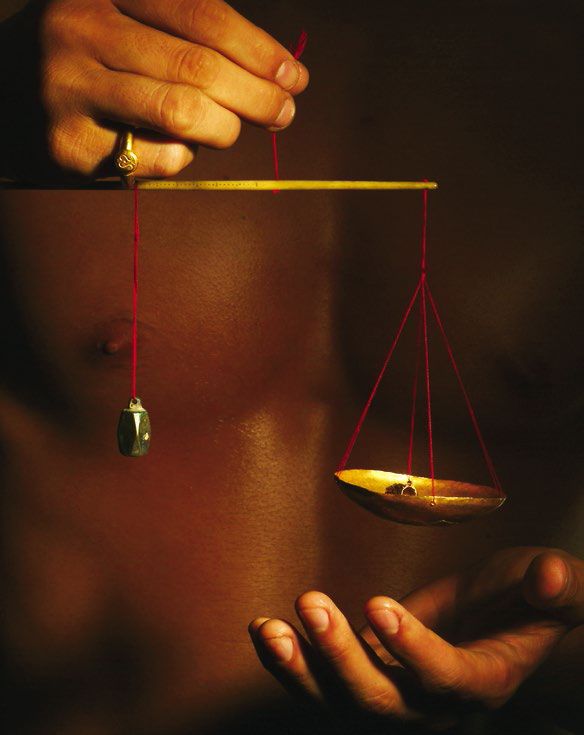

Gold was not strictly for women; in fact, men of high rank were more adorned than women, as seen on the very detailed illustrations in the pivotal late-16th century manuscript The Boxer Codex. “They had daggers, belts, sashes, rings, bangles, brooches … Even the clothing was adorned in finely flattened solid gold appliqués,” Treñas explains. One of the most prized pieces from his collection is a golden dagger sheath covered in intricate carvings. “It is made of hammered gold and is covered in beautiful geometric designs that look almost Etruscan.”

Pre-colonial gold discoveries come from all over the archipelago. Treñas’ exposure to pre-colonial gold began in his home province of Iloilo, when his mother started purchasing pieces from a find in Oton in the 1960s. “They had lots of pieces of gold jewellery with trade beads and my mother would purchase them for her to wear!” Currently all newly excavated gold belongs to the nation; however, collectors can still add to their own private troves through the numerous auctions and sales alimented by other private collections.

“In many pre-colonial Philippine societies, one’s life began and ended with gold,” explained Baker in the book Philippine Ancestral Gold, published by Ayala Museum in 2011. “Small pieces of gold were placed in a bag with a new-born infant’s umbilical cord after childbirth; prestigious gold ornaments were worn during life-crisis ceremonies and milestone events; spectacular golden treasures and heirloom porcelain were interred with the elite to ensure a successful journey to the afterlife.”

Through numerous efforts made by the public and private sector to document and preserve these precious artefacts, it seems as though this journey is secure. Centuries later, the memory of this halcyon society is embalmed in its gilded remnants, still vibrant and glittering today.#