TREASURE HUNTING – Lisa Guerrero Nakpil, The Philippine Star, December 13, 2020

Before this wicked pandemic, the practice of pharmacy was one of those necessary but utterly invisible professions: the license to dispense medicines and furthermore, to vet the right doses given your other medical conditions and other potions imbibed. The Philippine Pharmacists Association — which celebrated their 100th year last week — was even feeling underappreciated since they have not been counted among the list of essential front-liners. This, despite the fact that pharmacists risked their lives just as much, trudged to work in the absence of public transport and toiled selflessly in drugstores, dealing with those certainly ill, to man the dispensaries that were lifelines to the citizenry.

It was not always so. Pharmacy was at the forefront of the new age of science at the turn of the 19th century. It was a time inhabited by the likes of Sigmund Freud and (fictional) Sherlock Holmes, Charles Darwin and Louis Pasteur. If cartographers and conquistadores had defined the 18th century and computers and social media the 20th, scientists of every stripe — surgeons, chemists, horticulturists, CSIs, to name a few — were pre-eminent in that intermediate era.

The first pharmacists embodied this rational outlook and it attracted not just brainiacs but also swashbuckling men who found scientific exploration sizzled.

Pharmacy was introduced for the first time in the Philippines only in 1871 at its oldest university, UST. It graduated only five men, including Leon Ma. Guerrero, who was, however, the only one who made the active practice of it his life’s work and thus became the Philippines’ first licensed pharmacist.

My other favorite pharmacist is none other than “Hen. Luna,” who had far more in common with Guerrero than one would surmise. For instance, both were the kid brothers of famous artists. In the case of Leon Maria, it was Lorenzo Guerrero; for Antonio Luna, it was the sensationally famous Juan. In the annals of pharmacy, he was Guerrero’s archrival, competing for this or that important scientific award or position. It is a measure of both men’s genius that their achievements would be routinely mistaken in the history books for one or the other.

Luna was actually 13 years younger than Guerrero and had followed the same route in the five-year pharmacy course at the University of Sto. Tomas. He would, however, be packed off to Europe in the shadow of the Gomburza martyrdom and would wind up finishing his degree in Barcelona. It is said that he deliberately went after a doctorate in pharmacy in order to become the first Filipino to earn this title. He captured it in Madrid from the same university where Rizal and the rest of the Ilustrados studied.

But these men were not just on the vanguard of scientific exploration; they were also in the eye of a typhoon of political unrest and the painful self-realization of a nation. It was no accident that Jose Rizal described these times in terms of disease and cancers.

Antonio Luna would next move to Paris with his brother. Then, as now, the city was a center for medical breakthroughs and he worked with the scientists that would form the Institut Pasteur. Luna became fascinated with vaccines and began an inquiry on whether inoculations could curb disease. He delved into the 19th-century scourge of malaria, whose antidote interestingly was the progenitor of one COVID treatment, hydroxychloroquine, or Plaquenil.

Both men would become caught up in the Philippine-American War. Luna would become a ferocious general thanks to applying the logic of scientific principles to the art of war. Guerrero did the same by using his knowledge of botany to infuse scarce bullets with poison, making them doubly lethal.

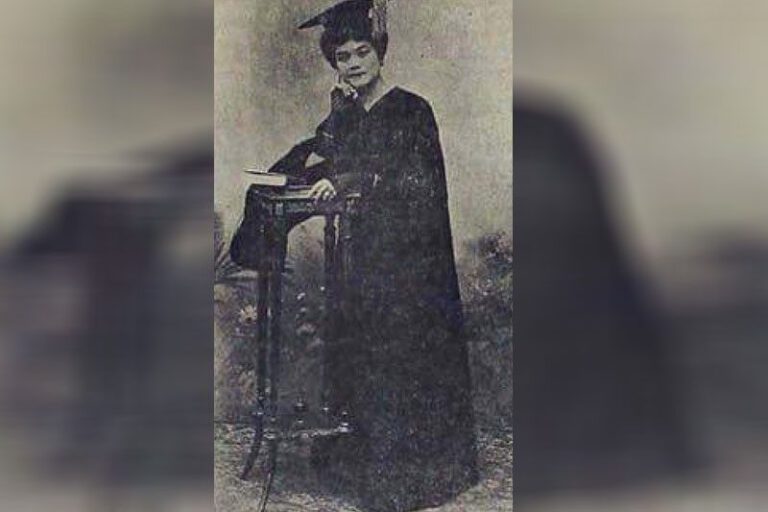

It was Leon Ma. Guerrero who would survive and become a leading light of the Philippine scientific establishment. He would become a member of the Philippine board of the St. Louis Exposition and founded the Liceo de Manila (today’s Lyceum.) Guerrero pushed his interest in botany to find herbal cures for practically everything that ailed the Filipino. His research is unmatched to this day. One of his star pupils was Filomena Francisco, who would become the first Filipino woman pharmacist. She is most important for showing the way for women to practice this heretofore male art. Filomena would marry my grandfather Alfredo, a classmate in pharmacy who would eventually become a doctor.

I never had the privilege of meeting Leon Maria. He died dramatically, clutching his heart, when Mother was not yet 13 years old in 1935. She was utterly devoted to him and would say he spent mornings studying various plants under a magnifying glass, recording their minutest changes in a sketchbook. She would read the newspapers to him every breakfast and was edified by his various comments of outrage. (I suppose this formed her sarcasm and a desire to be a political analyst.) It was not surprising that, one day when I announced I was writing a monograph on the Nakpils of Quiapo, she interrupted and said the better idea would be to write about dear old Leon Maria.

The very first minute I sat down at my computer to begin searching the internet for information on him, I was astounded by a photograph of a bust of Leon Maria, sadly on its ear, surrounded by broken toilet bowls and other refuse, behind what looked like a chicken-wire fence at the University of the Philippines. It appeared in a blog titled “Bulatlat,” written by Richard Gappi, an Angono reporter who was even more outraged, if that were possible, than me. Gappi told the tale of how his friend, Raul Funilas, an AV technician at the UP, would pass the sorry statue in the garbage heap daily, and finally, taking pity on the bust, trundled it home. I sent an email asking if I could meet them and they agreed to see me the very next day at the Bahay ng Alumni. I was there like a shot. Raul was more than a maintenance man; he was a poet and therefore a man with a more sensitive soul than others. He explained to me that there were some 5,000 words for “fish” and words for how they swam, jumped, and coursed through his beloved hometown on the Laguna de Bay. Finally, he invited me to view the bust of Leon Maria. I examined the statue and found at the back on a battered plaque the name of the national artist Guillermo Tolentino. Funilas confided that he had grown quite fond of the bust and that Leon Maria would talk to him in his dreams. I was startled and asked what was said. He replied that he didn’t know — he couldn’t speak Spanish. I pressed on. Surely, I asked, there was something he could make out? He nodded sheepishly and said, “Well, there were two words: ‘Abrir Botica,’ which roughly translated to ‘Open a pharmacy.’” I was floored. I next asked Funilas, very gingerly, what he had in mind and he quickly replied, “Nothing at all” — and I should just take Leon Maria home at last. I wrapped the bust in my shawl and took him to my car, driving straight to Mother, from whom I had kept all this until I was certain of retrieving him. Funilas asked me for only one thing in exchange: that Leon Maria be his guest of honor at the launching of his latest book of poetry, to which, of course, I agreed.

Leon Maria would give my mother much comfort in her last years. She would also admit that he would talk to her in her dreams. (Not too many people know that mother was prescient, deriving many of her premonitions from such moments.) What would he say to her? I asked. Her reply was the rather comforting prediction that “Things would, once again, be as they were.”

Does it not exactly foretell the circumstances of today? With the imminent arrival of vaccines to vanquish the pandemic, should not pharmacists once again be called to do their duty and take up once more an important role? Is it not, after all, by law that the pharmacist is empowered to administer all vaccines and decide who receives them? And is not the path to the future, as Pfizer and Moderna know, the opening of a pharmacy?#