Written by Anna Bueno, Updated Dec 3, 2019

Manila (CNN Philippines Life) — Whenever there’s food and a group of people huddled around a meal, there is always a good story.

A boatman in Lobo, Batangas, for example, may tell a story about the best goto in town. Our mothers may tell us stories about childhoods marked by the sweetness of merienda, or the brisk and garlicky smell of sinangag in the morning.

These stories are equally told by countless writers, cooks, enthusiasts, wanderers, advocates, and cultural workers who have tirelessly sought to understand the Philippines’ richly diverse culinary traditions. Our food stories have always been about an ongoing conversation on the ingredients, techniques, influences, tastes, and memories that bind us together.

Perhaps this is why the best stories about Filipino food are both deeply personal and universal. Each of us has our own food stories, and each of our stories are part of an interwoven canopy of tales that define what Filipino food culture is: wonderfully varied, satisfying, and ultimately a beautiful thing, the subject of unending marvel and fascination.

CNN Philippines Life lists six essential books that tell compelling stories of Filipino food culture, with the recognition that this is by no means an inclusive or complete list — but only an attempt to start another conversation on why we love food, and which food stories we love hearing over and over again.

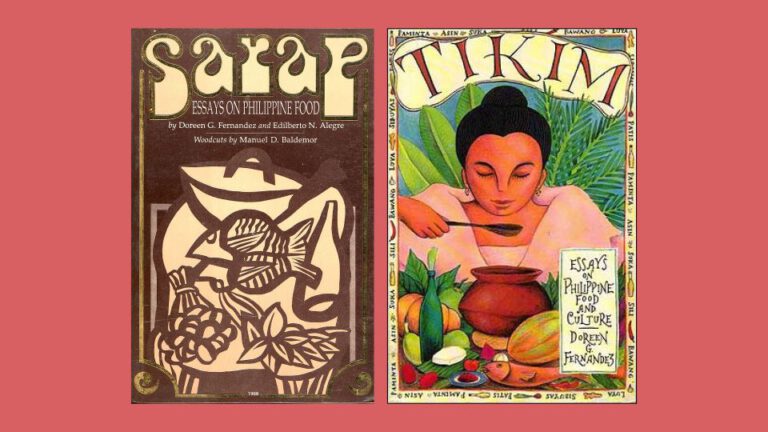

“Sarap: Essays in Philippine Food” (Doreen Fernandez and Edilberto Alegre, 1988); “Tikim: Essays on Philippine Food and Culture” (Doreen Fernandez, 1994)

“Food, like language, is living culture, and as such changes with the times. The old ways are tested and true; the new ways are not necessarily betrayals, if they are appropriate and result in good food.”

– Doreen Fernandez, from “New Ways with Old Dishes,” in “Tikim”

Today’s crop of Filipino food writers and readers owe much to Fernandez, who wrote not just about food, but how we experience it: in the streets, by the sea, in restaurants, during fiestas, as heritage, as history, as memory, as culture.

In “Sarap,” she wrote about the indigenization of Philippine food, a piece that is now widely considered to be required reading for anyone who wants to seriously understand our food culture. In “Tikim,” she gave sage advice on how to write about what eat: “It was about getting the reader to see through the words to the experience. It was choosing the words that echoed, that reverberated — umaalingawngaw. And then it was making the readers hear the silence between the echoes, and themselves load them with memory, sensation, and finally meaning.”

Fernandez’s advice would echo across generations, and itself reverberate to fill the gap she left behind. Celebrated food writers today dedicate their works to her; her words would continue to be spoken and read anew by cooks, anthropologists, journalists, and researchers. Even today she is still considered as Filipino food’s greatest champion.

Her essays continue to evoke secondhand memories, or memories so vivid we might as well declare them our own, as in her essay “Kinilaw Artistry at Old Sagay,” where she writes about the “ethos of freshness” of fishermen who prepare for her crab kinilaw dipped into a sawsawan of vinegar with a few seeds of siling haba. “Absolute heaven,” she wrote. “How do other mortals fare, never having known this?”

Thus in “Sarap,” “Tikim,” and other books and essays thereafter, Fernandez would be found not just in dining room tables, assured by the plate in front of her. She would be out into the world, “ingesting the landscape,” so that she may bring the landscape — and not just the food — to her readers. “If one can savor the word,” she wrote, “then one can swallow the world.”

“Memories of Philippine Kitchens: Stories and Recipes from Far and Near” (Amy Besa and Romy Dorotan; photographed by Neil Oshima, first edition 2006; updated 2012)

“…Filipinos often ask, ‘Is your adobo better than my mother’s?’ And we never take the bait. Of course, your mother’s adobo is infinitely better — everyone’s is!”

– Amy Besa

To ask about a person’s favorite food memories is to delve into a personal, often emotional process of linking food, family, and community. As recipes passed down from generations develop a life of their own, a dish becomes a catalyst, resurrecting memories long forgotten. In “Memories of Philippine Kitchens: Stories and Recipes from Far and Near,” author Amy Besa, as with any gracious host, invites us to make ourselves at home as she shares food stories, collected from friends (as with an “impeccable” begucan, or “pork loin boiled in vinegar and bagoong and fried in its own fat with tomatoes,” made by Susan Calo Medina and as recollected by her son Marc, who hails from Arayat, Pampanga), or culled from memories that are her own, as with her Nanay’s spring rolls. She also co-authored the book with her husband, chef Romy Dorotan.

The book is by no means a complete guide to the food of the archipelago, but is something better: a slow and reflective attempt to account for the authors’ multifaceted food memories, beautifully captured in photographs by Oshima. Each memory is followed by various recipes and interesting tidbits about food origins or family rituals.

Most generous are Besa’s and her husband’s painstaking efforts to give us their personal recipes based both on memories and research, which earns the book’s rightful place in the kitchen — propped up behind the chopping table while the sinigang simmers, perhaps — instead of in the living room as a coffee table book. “Memories” is proof that whenever we eat or cook, we do so as part of a timeless community, sharing in each other’s recipes and unending stories.

“Manga Tutul A Palapa: Recipes and Memories from Ranao” (Assad Baunto with Nash Tysmans and Ica Fernandez, 2018)

“An improperly prepared arowan ends up thrown by Babo in the lake, from whence it came.”

– Assad Baunto

“Manga Tutul A Palapa” (“Palapa Stories”) is a food book for our times. Baunto, who hails from Lilod Madaya, Marawi, pens an extended love letter to his hometown, telling several beautiful stories anchored on recipes from the women in his family. What holds the stories and recipes together is palapa: a condiment, appetizer, and flavoring agent basic to Maranao cuisine.

Published in 2018, barely a year after the siege of the city, the book paints a Marawi deeply beloved by its people. In telling us how to cook piyaparan a manok / pindialokan a manok, Baunto invites us to a movie theater “that provided a perfect cinematic frame on food, cinema, and the comedy of everyday life, a directorial debut vying for a Gawad Urian.” In sharing his Bae’s (maternal grand-aunt’s) recipe for kyuning (coconut turmeric rice), he strongly affirms that cooking brings him closer to home more than anything he has ever imagined.

In the book’s first pages, Baunto writes soberly to his Babo kolay (maternal grandmother) that “Marawi is probably lost but our food is not.” Yet he remains hopeful that people will read the stories and share the recipes within. In “Manga Tutul A Palapa,” one can then make a case for a Marawi fully alive, where food fills the soul, a place of memory never gone — only reimagined and transformed.

“Kain Na! An Illustrated Guide to Philippine Food” (Felice Prudente Sta. Maria, Bryan Koh; illustrated by Mariel Ylagan Garcia, 2019)

“A Philippine meal is incomplete without joy…eating and joy are so tightly linked.”

– Felice Prudente Sta. Maria and Bryan Koh

“Kain Na!” is less a compilation of food stories than it is a collection of Filipino food illustrations, captioned by two of the best authors we have — Sta. Maria (author of “The Governor-General’s Kitchen,” a painstaking collection of vignettes on the Philippines’ culinary history) and Koh (author of “Milkier Pigs, Violet Gold,” an in-depth tome on food traditions in the Philippine archipelago). Behind the illustrations is Garcia, a young artist and painter, whose work graces the book’s 209 pages.

Drawings and illustrations often take a supporting role, if any at all, in most food books published in the Philippines. More often, photos accompany stories. That gap is what “Kain Na!” seeks to fill, as the food drawings here are noticeably the text. Sta. Maria’s and Koh’s descriptions of various Filipino dishes — classified by mealtimes, occasions, functions, and places — tell us briefly about what we need to know, but it is Garcia who tells the stories.

The dishes sampled in the book are almost always depicted to serve large families. Not a groundbreaking observation, but an interesting one nonetheless, especially considering how the book’s title — “Kain Na!” translates to an invitation to eat. Garcia shows us that the act of eating in Filipino culture is largely communal, and food, among others, often functions as a channel for bonding and communication.

Garcia, in using watercolor, also depicts dishes in the context of the home or community. The technique also softens bold colors and lends subtle textures to soups and assorted rich viands. Both are nods to creature comforts and Filipino food’s homemade quality (which may be lost in digital renderings). If anything, Garcia’s drawings lack just a little bit of sheen, for when we’re supposed to be looking at a sizzling sisig or a really oily lechon.

Still, it’s a delight to go over the book as an exercise in whetting the appetite and identifying iconic dishes by color and texture alone. One leisurely goes through “Kain Na” and realizes Filipino food is not just delicious — it has always been a distinctive work of art.

“Makisawsaw: Recipes x Ideas” (Edited by Mabi David and Karla Rey, 2019)

“Let’s change the world with food.”

– Charlene Tan, “Can We Change the World with Food?”

“Makisawsaw” stands out among the books on this list for many reasons: its 36 food and sawsawan recipes are vegan, its essays explicitly call for a rethink of our unsustainable consumption of resources, and overall it observes how distant we’ve grown from the sources of our food. The book takes cue from the violent dispersal of the condiments factory workers of Nutri-Asia — who went on strike in 2018 to push for employment regularization — and tackles issues such as seed patenting, the rice liberalization law (via comics), and insecurity in land tenure, among others.

While on face value, the heavyweight issues in “Makisawsaw” seem to contrast with nostalgic food memories or comforting recipes in books of this kind, the essays here couldn’t be more aligned with the latter. For example: When we revere our mothers’ or grandmothers’ slow, old-fashioned ways of cooking, does that not reflect the value placed on fresh, chemical-free ingredients, and cooking with as little artificial preservatives as possible? Whenever we reminisce about visits to farms, fishponds, or wet markets, does that not highlight the persons who produce our food? And when we appreciate how nature freely gives her bounty, or how we all share in the biodiversity of our food resources, is that not a recognition against corporate ownership of our native seeds and crops?

“Makisawsaw” then is the inevitable extension of our continuing food conversations. Insofar as it is significant to document how food becomes identity, memory, culture, and heritage, the book recognizes the fragility of those relationships, by pointing out the powerful forces that threaten them.

To preserve food as memory, identity, culture, and heritage, therefore, we have to act. In “Makisawsaw,” we are reminded that everything is political, including food, and before it’s too late, we have to confront the food issues that we’d rather not talk about in the dining table.

***

This article has been edited on Dec. 10, 2019, to more accurately reflect a reference to begucan, in “Memories of Philppine Kitchens.”