Most of us may be afraid and cautious of this invisible virus possibly lurking in our vicinity. But for the economically vulnerable, it is the untrustworthy authorities that they are most afraid of during this quarantine. With Duterte’s order to shoot anyone who does not obey, the police were given even more power to assert their authority over the vendors and homeless.

By NATHALIE D. DAGMANG

Bulatlat.com

MANILA — March 15 was the first day of the Metro Manila community quarantine.

But while everybody else was quarantined inside their homes, its street vendors and dwellers felt that they could not stay in theirs.

For the food vendors of Escolta Street, Manila, the bangketa (sidewalk) is home. It is their only source of livelihood. They sell candies, cigarettes, newspapers and affordable snacks such as fishballs, peanuts and fruits to commuters, students, and office workers.

Suddenly, peddling was not allowed. They were told to stay off the streets, forcibly sent to non-existent houses.

I knew them from a research project I was working on with fellow art practitioners. For almost four years, we visited Escolta’s sidewalks to talk to vendors, organize workshops with them, and reflect on what it means to be part of their neighborhood.

From my interviews and fieldwork, I know how much they relied on their relationship with their suki (regular customer) to keep their families afloat. They only earn 150 to 300 pesos a day, with a profit margin of one to three pesos for each item sold.

This is not enough for their needs if we add up their daily expenses and the capital needed to buy goods for the next day. They manage to earn because of their stable relationships with their suki, supplemented with gifts and other gigs. For them, the bangketa provides relief, stability and security that they need amidst poverty.

During the second day of the quarantine, I reached out to the vendors to check on them.

In just a few hours, I was flooded with messages calling for help and expressing their frustration over their local barangay’s response to their calls.

“Paano ba kami mabubuhay kapag ganito ang sitwasyon, walang hanapbuhay, pati asawa ko wala ring byahe trucking nila. Paano na kami kakain, Nat?,” (“How are we supposed to live through this situation when all our sources of livelihood are cut off? How will we eat?”) one asked.

I received photos of a deserted Escolta street. The peanut vendor who tried peddling during the first day of quarantine described it as a ghost town. She went back home at midday with not a single pack of peanut sold.

They hoped to receive relief goods from their barangays after President Rodrigo Duterte’s national address the previous night. “We have enough supplies,” Duterte said. His promise that no one would be left hungry was met with praise from his followers.

But there are too many unanswered questions for those on the ground: Where are the supplies? How and when can they get them? What are the plans for relief distribution?

With no transportation available, it was impossible for me to secure food supplies, let alone bring these from my hometown of Marikina to the vendors in Manila. At this point, the quarantine protocols were vague. It was still unclear how the administration planned to address this crisis.

My colleague and I scrambled to look for communication channels to Manila Mayor Isko Moreno. I posted a screenshot of the vendors’ messages on Facebook to ask for leads. I approached a friend working with the President’s communications office, who then called on contacts with the local city administration and the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD).

Distrust and fear

I felt a glimpse of hope when I got confirmation that a DSWD official was on her way to them.

I informed one of the homeless vendors, but they were not as enthusiastic with the news. Their long struggle with the agency has led to them to distrust anyone who is associated with it. When the DSWD official failed to call by evening, I received a message from them saying “‘Wag nyo na kami paasahin, ate. Baka hindi naman ‘yan totoo.” (“Don’t give us false hope. That’s probably not true.”)

The official arrived past 11:00 p.m. and had to leave the relief pack in the barangay office. By that time, the police forced the waiting vendor to vacate the sidewalk.

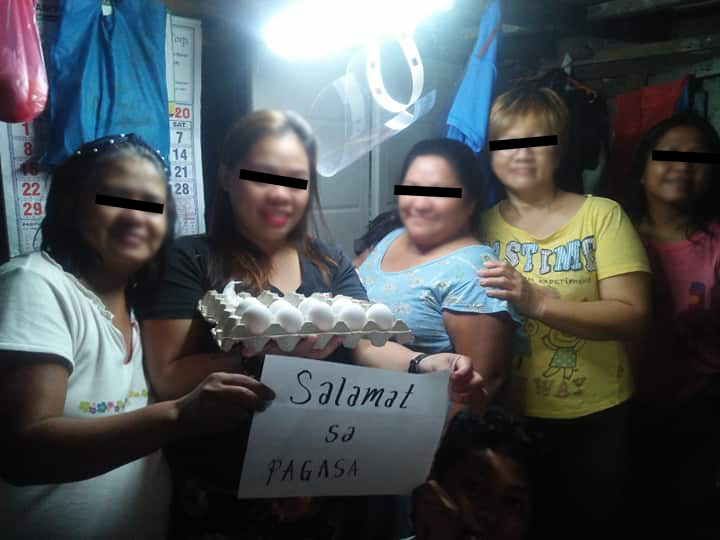

The peanut vendor who received a pack of relief goods that night pleaded for more to be given for their relatives and neighbors, but the official only brought supplies for one family. She decided to split the food with her sister’s family living in the same house.

This may seem like an isolated case, But on a broader note, the vendors and homeless are not strangers to incompetence, corruption and abuse of power by authorities.

Vendors were the first targets in revitalization efforts to “beautify” the poverty-striken city of Manila. During his first few months in office, Mayor Moreno boosted his strongman image by confiscating the carts of illegal vendors and street dwellers and flushing the streets. Even when he claimed to discipline the city’s corrupt police officers, vendors recounted still being forced to pay daily butaw (literally translated to “membership fee” but is technically a form of extortion by police officers) to continue selling on the streets.

The homeless are constantly in hiding from police and DSWD authorities who keep on confiscating their belongings and conducting “rescue” operations of their children, bringing them to the far-off Boystown in Marikina City, where they were reportedly fed either spoiled or insubstantial food. For them, being “rescued” is an ironic situation, worse than being locked in jail. Concrete programs to help alleviate poverty of among those who have no choice but to sell illegally and sleep on the streets are few.

When I told the vendors that a new evacuation center was put up in Delpan sports complex, one feared that it might be a trap for homeless people like them. According to her, street children are still being “rescued” even during the quarantine. “Akala mo ate tinutulungan yun? Hindi po. Pagkatapos iba-byahe sa Boystown yun,” (You think they’re being helped? No. After, they’re being sent to Boystown.) she said.

Also in an anxious tone, the peanut vendor asked me if her call for help sounded like a complaint against the DSWD. She feared that police might get back at them for making them look bad. “Baka mamaya ratratin na lang kami dito, natatakot ako,” (“I’m afraid that they might shoot us.”) she said.

Most of us may be afraid and cautious of this invisible virus possibly lurking in our vicinity. But for the economically vulnerable, it is the untrustworthy authorities that they are most afraid of during this quarantine. With Duterte’s order to shoot anyone who does not obey, the police were given even more power to assert their authority over the vendors and homeless.

Class-based mobility under the ECQ

Apart from problems with communication and finding resources, one of the challenges of organizing a relief drive during the ECQ is transportation.

With checkpoints in place and nearby businesses closed, the delivery of the food packs took longer than expected. The whole process of ordering, arranging transportation, delivery, repacking and distribution took me almost three days. Transportation for bulk items is expensive. Luckily, the market stall offered to deliver goods to us for free while another volunteer offered to drive and bring the repacked goods to Escolta, in the spirit of bayanihan.

There was also the problem of inconsistent and seemingly arbitrary curfew and checkpoint rules. In most middle to upper class neighborhoods, the curfew is at 8:00 p.m.; in many informal settlements, it is cut short to 3:00 PM.

The vendors told me that barangay officials would shout at them just for going out briefly to take a much-needed walk outside their cramped houses. In checkpoint lines, they are cramped against each other and intimidated by the police. In contrast, individuals from middle to upper class neighborhoods are only asked brief questions and greeted with a smile. Even during a health crisis, the question of mobility is still based on class.

We had to rush the distribution process because of this curfew. On the ground, it was difficult to observe social distancing because everybody was in a hurry. I had to call them one by one so they could venture quickly outside their homes and rush to the meet-up place.

Since the police tried to disperse the vendors and homeless waiting for the delivery on sight, the vendors had to meet up with the volunteer in a hidden corner of Escolta. They were also worried that other hungry families not on the list might flock to the area. I had to label each bag of relief goods so as to prevent people from fighting over them.

At the end of it all, I felt exhausted and overwhelmed. Although colleagues and friends helped me throughout this process, organizing a relief drive is still a daunting task.

It feels frustrating knowing that what we were doing was still inefficient and unsustainable. The government has all the resources, communication channels, control over transportation, and the personnel for checkpoints and local units. They are the ones mandated, by virtue of our votes and taxes, to provide for our needs during calamities such as this. But where are they now?

A slow death for the economically vulnerable

After three weeks of the ECQ, the inaction of the vendors’ respective barangays has become unbearable.

Some vendors were given relief supplies of only two kilos of rice since the start of the quarantine; others received none at all. A vendor asks if their neighbor or relatives who live in another neighborhood can also get some help.

The need for more relief operations never ends. I know that we lack enough volunteers and goods for every household in their neighborhood, which might add up to a thousand families. I had to call on contacts with connections to churches and bigger charities and manage the expectations of our vendor contacts.

One vendor called for help in demanding relief goods from their barangay chairperson. I posted her message and crowdsourced contacts from media.

At the sight of a media van arriving in their neighborhood, the whole community went out of their houses and applauded. The chairman was forced to explain why it was taking them so long to provide food to their constituents.

After a few days, the vendors finally got three kilos of rice. They are not expecting food packs from the mayor anymore. The peanut vendor told me that the supposed cash aid from the DSWD is their last hope. Even that is uncertain, but they have nothing else to look forward to.

After each of Duterte’s national addresses, the vendors are given vague promises that they will never go hungry and that help is on its way. They just have to wait.

“Hindi kami mamatay sa virus. Sa gutom kami mamamatay ng pamilya ko,” (My family won’t die from the virus, but from hunger) the peanut vendor told me.

For most of us, staying at home and being surrounded by the military may provide feelings of security and relief from any possible health threats. But when you are hungry, locked down and helpless, it’s hard to feel anything else but the incessant pangs of starvation.

Imposing quarantine on vendors and street dwellers without providing for their urgent necessities only makes them more vulnerable to the disease. They are forced to go out to source their own food, to ignore symptoms with the thought of possible hospital bills, and to protest in groups when they can no longer rely on the authorities to help them, only to be sued and crammed into detention centers where physical distancing is impossible. We should all be worried. As World Health Organization WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus tells us, in this pandemic, we are only as strong as the weakest among us.

About the author

Nathalie R. Dagmang is a lecturer at the Ateneo de Manila University, Department of Fine Arts. She is a member of the Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP) and part of the Manila research team of the South East Asian Neighborhoods Network (SEANNET) which focusses on the changing neighborhood of Escolta amidst Manila’s city revitalization programs.

Reflections on Relief

What is it that comforts, eases, alleviates, and allays? This is a series of accounts sourced by the Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP) from creatives and cultural workers in response to the idea, experience, and practice of relief during the time of the COVID-19.

Since the Enchanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) in March 2020, artists actively contributed to citizens’ movements for provide aid to frontliners and the most vulnerable in society. As this extends, we ask: in the face of global pandemic and local crises, how can the experience of respite and assistance affirm the basic need for human agency, compassion, and dignity?

The post Responding to Escolta’s street vendors: How do we provide relief and security to the economically vulnerable? appeared first on Bulatlat.