By: Kurt Dela Peña – Content Researcher Writer / @inquirerdotnet

INQUIRER.net /August 15, 2022

MANILA, Philippines—When the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) was still a bill, the National Union of People’s Lawyers (NUPL) said there’s a danger with how the government can construe legitimate dissent within the “overbroad” definition of terrorism.

The NUPL had said: “The bill contains imprecise and poorly worded provisions on the definition of ‘terrorist act’ as it seeks to criminalize threats to commit, planning to commit, conspiring and prosing […] the vague concept of ‘terrorist acts.’”

“The danger therein lies with how the government can construe legitimate acts of dissent or opposition within these definitions—it gives the government almost free rein in determining who are suspected terrorists,” it said.

But despite the strong opposition, the bill, which was considered a setback for human rights, was still signed in July 2020 by then President Rodrigo Duterte, with Malacañang saying that the law reflects a serious commitment to fight terrorism, a global problem.

While petitions were filed to challenge its constitutionality, the Supreme Court (SC) decided to uphold most of the law, saying that the motions for reconsideration were denied with finality last April.

The SC decision meant that Filipinos will have to live with the controversial law, which was criticized by human rights groups for its provisions that could be used to silence legitimate dissent.

The government had said that the law passed through intense deliberations to make certain that it will not infringe on people’s rights, but rather defend their rights to life, liberty and property as well as the freedom from fear.

But last Aug. 9, a memorandum was issued by the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (KWF) to call on its personnel to stop the publication and distribution of five books that it deemed “subversive” for promoting “anti-government ideologies.”

The memorandum, which was signed by commissioners Carmelita Abdurahman and Benjamin Mendillo, cited Section 9 of the ATA—“inciting to commit terrorism”—as basis to cease the publication and distribution of the books.

NUPL president Edre Olalia told INQUIRER.net that the KWF’s move cemented the concerns expressed against the ATA—that the law is “overbroad” and could be used to silence dissent.

He said “we had well-grounded and reasonable fear[s] then and we have growing examples all around us now that this is going to be so.”

Subversive books?

The books, which Abdurahman and Mendillo considered “subversive” are these:

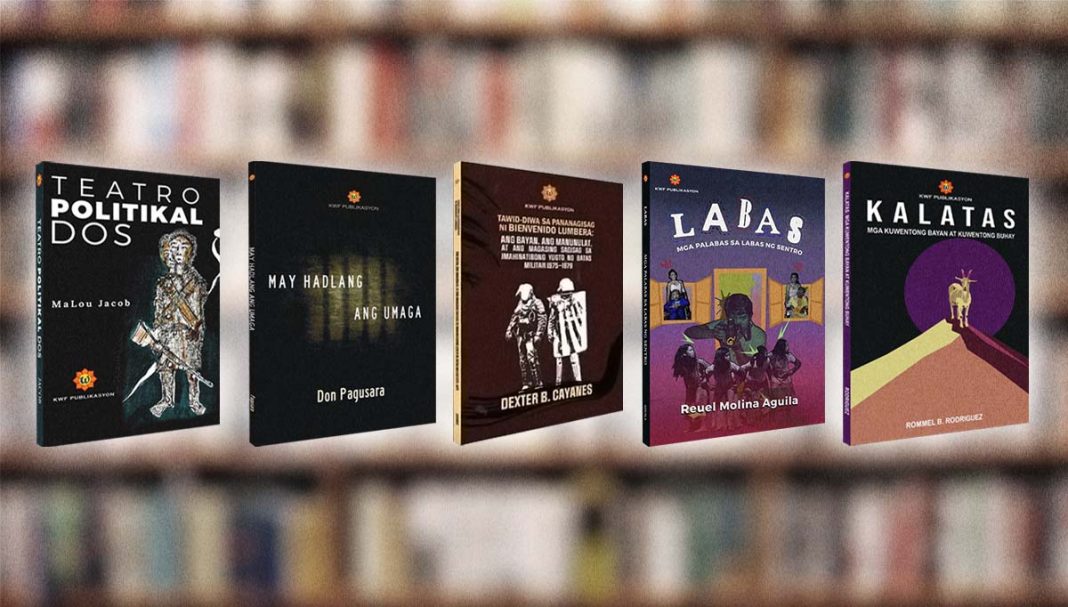

- Malou Jacob’s “Teatro Politikal Dos”

- Rommel Rodriguez’s “Kalatas: Mga Kuwentong Bayan at Kuwentong Buhay”

- Dexter Cayanes’ “Tawid-diwa sa Pananagisag ni Bienvenido Lumbera: Ang Bayan, ang Manunulat, at ang Magasing Sagisag sa Imahinatibong Yugto ng Batas Militar 1975-1979”

- Don Pagusara’s “May Hadlang ang Umaga”

- Reuel Aguila’s “Labas: Mga Palabas sa Labas ng Sentro”

Some of the books—Teatro Politikal Dos, Kalatas and May Hadlang ang Umaga—had already been published by the commission and featured in the “KWF Publikasyon Paglulunsad 2022” last April 29.

Mendillo, the commissioner for KWF administration and finance, said: “Right now, we are stopping the books with subversive texts. We will see, moving forward, the instructions of [the] director general of the commission.”

“NTF-Elcac (National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict) is not yet in the picture, but on our own, we have reviewed the text and we have found evidence, explicit idealism, ideology, CPP-NPA taglines,” he said.

The KWF memorandum ordered one of its units, the Sentro ng Wika at Kultura (SWK), to stop printing the books that contained “political, subversive and creative literary works with subliminal ideologies that encourage to fight the government.”

Killing critical thinking

Human rights group Karapatan secretary general Cristina Palabay said the move “den[ies] the public with much-needed literature and materials encouraging critical thinking and knowledge on Filipino history and language.”

She said the memorandum issued within the KWF “sets a dangerous precedent in the exercise of academic freedom and the promotion of creative and scholarly work,” adding that the move was “shameless and idiotic.”

Last year, some “subversive” books were also removed from the libraries of state universities—Kalinga State University, Isabela State University and Aklan State University.

It was then a bid to remove all books, research work or any reading material that has reference to communism, socialism or communist rebels who have been waging a guerrilla war for more than 50 years now.

The premise, especially by the military, was that books with socialist or communist content poison the minds of the youth into rebelling against the government, never mind the root causes of rebellion, like poverty.

Elvira Lapuz, librarian of the University of the Philippines Diliman, had said that getting rid of reading materials as part of the government’s war on insurgency disregards critical thinking and literacy.

Some of the books that were removed from the libraries of the said state universities were these:

- Building People’s Power

- Defeating Revisionism, Reformism, and Opportunism

- Crisis Generates Resistance

- Building Strength through Struggle

- Continuing the Struggle for Liberation

- Louie Jalandoni, Revolutionary: An Illustrated Biography

- Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law

- Declaration of Undertaking to Apply the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and Protocol I of 1977

- People’s Struggle Against Imperialism, Plunder and Wars

- The Declaration and Program of Action for the Rights, Protection and Welfare of Children

- The GRP–NDFP Peace Negotiations Major Written Arguments and Joint Statements for September 1980 to June 2018

- NDFP Adherence to International Humanitarian Law: Letters to the International Committee of the Red Cross and the UN Secretary General

- NDFP Adherence to International Humanitarian Law: On Prisoners of War

- The NDFP Reciprocal Worrying Committee Perspectives on Social and Economic Reforms

“It shows how little faith we have in our youth,” she had told INQUIRER.net. “It clearly says that we do not trust them at all to be conscious, aware and critical of the materials they have or have been given access to.”

Is it legal to ban books?

The KWF told SWK directors that the books should not be distributed so that “we would not be accountable to Republic Act No. 11479, particularly Section 9 on inciting to commit to terrorism.”

Section 9 of the ATA states that “any person who, without taking any direct part in the commission of terrorism, shall incite others to the execution of any of the acts specified in Section 4 hereof by means of speeches, proclamations, writings, emblems, banners or other representations tending to the same end, shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of 12 years.”

But Olalia stressed that there’s no law that provides a legal basis to label books as subversive. During the administration of the late Fidel V. Ramos, the anti-subversion law was repealed, opening up avenues for unarmed and parliamentary struggles for government critics, especially the Left.

He said “[there’s] none that I know of” because the Anti-Subversion Act has been repealed in 1992 by Ramos. He said, however, that the law only refers to membership in so-called “subversive organizations.”

Likewise, Olalia said that one presidential decree, which was issued by the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr., is inapplicable as it refers to illegal possession of “subversive” materials or publications.

He said: “The closest would be the crime of sedition and related crimes of seditious publications. But no legal animal as ‘subversive’ publications.”

Beyond KWF’s mandate

Albay Rep. Edcel Lagman said the KWF order to ban “subversive” books in schools and public libraries was an attempt at “thought control” and a violation of freedom of expression.

Lagman explained that the KWF, as created by Republic Act No. 7104, or the Commission on Filipino Language Act, has “no power whatsoever to ban and censor written works in Filipino.”

He stressed that the KWF is “not an adjunct of the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict” nor an “extension of the Anti-Terrorism Council.”

“The action of the KWF of banning the subject books for purportedly violating Section 9 of RA 1147, or inciting to commit terrorism, is an unwarranted sanction by an unauthorized agency without trial and due process,” he said.

Lagman, who vowed to push a House investigation of the KWF memorandum, slammed the directive as “patent thought control and unmitigated censorship” and that “the memorandum is an outlaw, which must be slain on sight.”

“Memorandum No. 2022-0663 dated Aug. 9, 2022 of the KWF banning five books in Filipino as ‘subversive’ is a liquidation of the freedom of expression, which is enshrined and protected by the Bill of Rights,” he said.