Rappler.Com, Oct 23, 2020, Ana P. Santos, Research Leika Golez and Cristina Chi In partnership with the Pulitzer Center

MANILA, Philippines

Part 1: Long-haul fishing is notorious for its exploitative working and deplorable living conditions. Solitary months in the high seas place crew at the mercy of extreme weather disturbances and at risk of physical abuse by malevolent captains.

Jesus Gaboni and 8 other men carefully wrapped Raul Calopez’s body in a white blanket before storing it in the ship’s freezer. Afterwards, the men gathered around in silent prayer.

Some Chinese crew members joined them as they lit a candle and laid out some food, a bottle of mineral water, and Coke. As a final tribute, they lit a cigarette and hung it on the freezer’s lock.

More than two weeks had passed since the fateful day of December 31, 2019. The sun in the rich fishing grounds in the waters off Peru was beating rays of blistering heat on the men working on the ship.

Deckhand Calopez was fixing the ship’s “parachute,” the thick metal line that serves as an anchor, when he suddenly fainted, hit his head on a pipe, and momentarily lost consciousness after he fell to the floor.

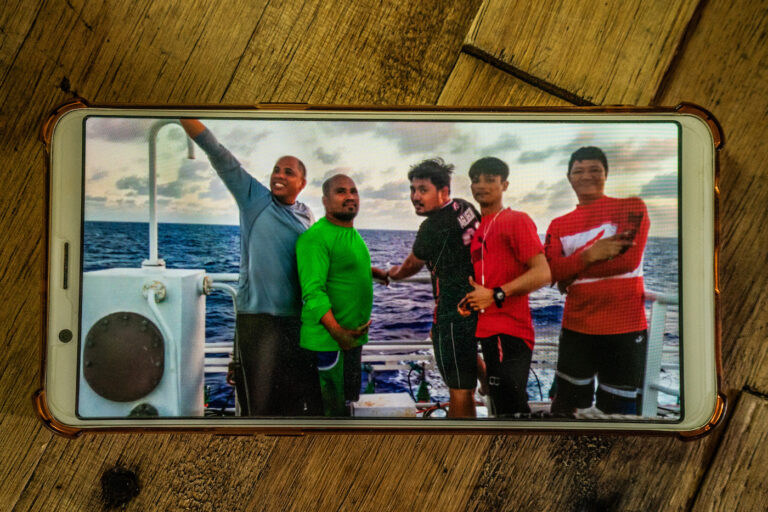

He went back to work after a few days but often complained of headaches and difficulty breathing. As his condition deteriorated, the men on board the Fu Yuan Yu 7874 fishing vessel took turns looking after Calopez, feeding him porridge, giving him sips of water, and helping him to the bathroom. Crew members shared photos and videos of Calopez lying in bed, visibly weak.

Gaboni – “Gabo” to the 40 other Filipino seafarers of the vessel that had been out in the fishing grounds of the Atlantic Ocean since March 2019 – pleaded with their Chinese captain to bring Calopez to a doctor. It fell on deaf ears.

A bulky man of almost 6 feet, Gaboni’s physical presence could be intimidating if it were not for his gentle protective aura. On land,his years working as a security guard trained him to be a person of quiet authority, the one you count on for a welcoming smile and also the one you would turn to for help.

At sea, he was the group’s natural choice to be the leader they entrusted their lives to.

Desperate to ease Calopez’s pain, the men tried asking their captain for medicine but the attempt was futile.

“Binigyan kami ng gamot dun, eh, hindi naman namin maintindihan kasi Chinese ang sulat,” he said. (They gave us medicine but it was in Chinese characters that we couldn’t understand.)

More than two weeks would pass after the accident, before Calopez was transferred to a sister Fu Yuan Yu vessel where he was supposed to have been attended to by a doctor. That was the last time the crew saw Calopez alive.

On January 19, Calopez’s body was transferred back to the Fu Yuan Yu 7874 where crew members buried him.

Fast forward: Trauma, anxiety

Sleep eludes Gaboni. He gets only three to four hours of sleep a night – “like a chicken,” he chuckled. When he does get to sleep, his screaming and grumbling wake his wife.

“Minsan ginigising ako ng misis ko, galit na galit daw ako. ‘Ano yung sinisigaw mo na para kang galit?’” he recalled her asking him. (Sometimes my wife wakes me up because I sound angry. She asks why am I shouting and what am I angry about?)

It’s been more than two months since Gaboni returned to the Philippines but he still has flashbacks of the year he spent in Peru onboard the Fu Yuan Yu 7874 – the long nights that stretched to early morning hauling squid as big as his arm, cleaning it, freezing it. The bland porridge and the instant noodles that passed for food. The filtered drinking water that came out of the pipes smelling and tasting like rust.

The company of his wife and three children is the salve to the physical hardship he had to endure as a deep sea fisherman, but when Gaboni finds himself alone, feelings of helplessness creep in accompanied by the memories of illness and death.

“Naiisip ko pa rin si Raul. Hindi porke’t nakarating na ako dito nang matiwasay at nasa magandang kalagayan na ako, kumbaga safe na ako. Iniisip ko pa rin ‘yung kasama ko,” said Gaboni. (I still think of Raul. Just because I am home and have arrived safely, it doesn’t mean that I don’t think of my crewmate anymore.)

“Sa maiksi lang na panahon na pinagsamahan namin hindi ko na rin tinuring na kaibigan kundi bilang kapatid [si Raul] dahil sa lahat ng crew doon na Pilipino, ako ‘yung pinakamatanda sa kanila,” said Gaboni.

(We were together for only a short time but I didn’t think of Raul as just a friend. I thought of him as a brother because among all the Filipino crew, I was the oldest.)

Life at sea

Overfishing driven by an insatiable global demand for seafood plus climate change are pushing fish and the crews who catch them farther from shore. Long-haul fishing boats venture out for months at a time – sometimes, years – into the high seas, disconnected from the rest of the world and away from legal surveillance and tracking.

The fatigue from the long months of working at sea makes seafarers prone to injury and accidents. The European Maritime Safety Agency estimates about 4,000 marine casualties and incidents occur annually, injuring almost 1,000 seafarers.

Apart from the brutal working conditions, being cut off from their loved ones and isolated on a ship add to the reason why a high number of seafarers suffer from depression.

Other studies show that feelings of helplessness when they witness the death of a crewmate can leave long-lasting emotional trauma.

Philip Cachero, 32, wasrocked by a mix of shock and sadness after Calopez’s death. Cachero was one of the men who helped lay Calopez to rest, and for days after, he tossed and turned in his narrow bunk bed, tormented by thoughts about their boat sinking and the overwhelming fear that any of them could die next.

“Nawalan kami ng gana magtrabaho simula nung nangyari. Gustong-gusto na po talaga namin umuwi. Kasi, what if sa amin naman mangyari yun?” said Cachero. (We didn’t feel like working after that happened. We wanted more than anything to go home because what if that happened to us?)

Floating prison

Long-haul fishing is notorious for its exploitative working and deplorable living conditions. Solitary months in the high seas place crew at the mercy of extreme weather disturbances and at risk of physical abuse by malevolent captains. The New York Times called long-haul fishing vessels “floating labor camps” and the mostly male crew who work on them “sea slaves.”

“Pag nalalasing ’yung ibang Chinese, pinapasok ’yung kuwarto namin, pinag-ti-tripan kami, binabatukan kami,” said one seafarer who asked to remain anonymous, fearing he could be blacklisted by manning agencies and ship owners. (When some of the Chinese crew get drunk, they barge into our room and bully us or smack us on the head.)

“Di baleng malaglag ka, basta lang hindi malaglag ’yung pusit.” said Fernando Tangalin, a seafarer on board the Fu Yuan Yu 7877, describing the workplace hierarchy. (It doesn’t matter if you fall off the ship, as long as the squid don’t.)

There are an estimated 41,000 migrant fishermen but the number could be closer to 100,000 with many trafficked on boats and falling under industry safeguards like pre-departure training that would prepare them for a life in the high seas. Worse, some ships do not always have tracking systems or turn them off to evade detection if trespassing into protected waters or overfishing.

“And once they are already on board, who gets to check how they are doing? When something happens, the captain holds your fate in your hands. And of course, there is always the possibility of being dumped at sea,” said Marla Asis, director of research at the Scalabrini Migration Center in Manila.

A crew working together in confined space allows for a closer sense of camaraderie but it can also amplify experiences like the distress over the death of a crew member. According to a study published by the Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, “The traumatization is even more likely if an unaffected crew member empathizes with the primary victim and…experiences being unable to help.”

Ryan Tabulod, a 7874 crew member, can’t help but think of the similarities between him and Calopez. Like Calopez, he also had two young children and a wife waiting for his return.

“Awang-awa talaga ako kay Raul at saka sa asawa niya at ang mga anak niya. Sana maiuwi na ‘yung katawan niya,” said Tabulod. (I really feel sorry for Raul and his wife and kids. I hope his remains are returned to them.)

Among the most dangerous jobs

Seafaring is not only one of the most dangerous jobs in the world. Seafarers also experience dangerously high levels of mental stress and have contemplated suicide perhaps more than any other occupation.

Though studies on mental health of seafarers are still sparse, seafarer welfare organizations and manning agencies have responded by making online and virtual counseling and emotional support services available to those suffering from depression or having suicidal thoughts.

But compared to their merchant marine and cruise liner counterparts, these services are mostly out of reach for deep sea fishers whose spartan living conditions and stations in the middle of the high seas do not offer the luxury of connectivity or even an occasional shore leave.

Additionally, maritime laws that vary by country do not always classify deep sea fishers as seafarers, leaving them in an ambiguous category when it comes to worker rights.

The International Labour Organization’s Work in Fishing Convention aims to set international standards for the protection specifically of fishermen, but among the major commercial fishing countries, only Thailand has ratified the convention. The Philippines, among the biggest suppliers of seafarers in the world, has not signed on the convention.

Oblivious to pandemic

These conditions were exacerbated by the COVID-19 outbreak, which has kept an estimated 300,000 seafarers quarantined in their ships, with little to no chance of being replaced by a fresh crew, according to the International Transport Workers Federation (ITF).

The Philippines is at the center of this maritime crisis where a global pandemic has collided with life at sea, pinning deep sea fishers against a corner of compounded hardship.

The crew on the Fu Yuan Yu 7874 began their journey back to the Philippines from Peru last March. In May, their ship docked in China, where they got their first mobile connection in over a year.

They were shocked to hear about a global pandemic that closed down the world and prevented them from disembarking. The crew had heard scraps of news about a virus in December but they refused to believe it, thinking it was an excuse to keep them onboard working.

“Buti pa po ‘yung mga nakakulong, mga nakabilanggo. May mga dumadalaw. May mga alam sa mga bali-balita, kung ano nangyayari sa mundo. Kami, wala talaga, as in zero, kasi nasa dagat lang kami. Di namin alam ang mga nangyayari. ’Yung COVID-COVID na ’yan, hindi namin alam ‘yan,” said Cachero.

(Prisoners who are locked up in jail are better off. At least they get visitors. They get news about what is happening in the world. For us, totally nothing. Zero because we are out at sea. That COVID virus, we didn’t know anything about that.)

Travel restrictions related to the pandemic stalled the 7874 in China, along with other vessels of the same fishing company. The ships were also carrying the remains of sailors who had died on board. On June 6, Stanley Jungco also met an accident and died on board. On another ship, Mark Felix Guial died of unknown causes after suffering intense stomach pain.

The men would sail back to the Philippines only in July – after almost three months of being stranded by the pandemic and more than a year of living in the ocean.

It was only the remains of Guial and another unnamed seafarer’s that were repatriated to the Philippines and returned to their families.

In the shuffle and transfer to the Star Mariner that would eventually sail back to the Philippines, Jungco’s remains were left behind in a mortuary in Fuzhou, southern China. Calopez’s body was left in the freezer of the 7874 which sailed back to Peru. A locator on a global maritime tracking website indicated that the ship’s latest position as of October 13 was west of the Peru exclusive economic zone, already out of range.

Correspondence between the Philippine embassy in Chile – which has jurisdiction over Peru – and Calopez’s family showed that communicating with the ship is difficult, and varying inter-country protocols are complicating the repatriation of his remains. If the ship docks in Peru this October, there may be a possibility of retrieving Calopez’s body. By then, it would be almost a year since he had died.

“Hangga’t hindi naiuuwi ’yung bangkay (ni Raul) at hindi naililibing, para sa ’kin hindi pa rin ako komportable,” said Gaboni. (Until Raul’s body is returned and buried, I will not be at peace.)

Don Eliseo Prisno III, a research associate at Seafarers’ International Research Center at Cardiff University, described the recurring thoughts of helplessness and grief as heightened anxiety.

“Closure is essential to grieving. Until the bodies are returned and the families – as well as the seafarers – can have a final goodbye, grieving and closure will be difficult,” said Prisno.

When the men were at sea, they prayed for salvation, for rescue. Now home, they pray to God for those who did not make it alive. And for having survived, they ask for one more thing: forgiveness. (To be concluded) – Rappler.com